![]() Part I

Part I

Perceptual

factors![]()

1

Writing

and

speaking

The origins of writing

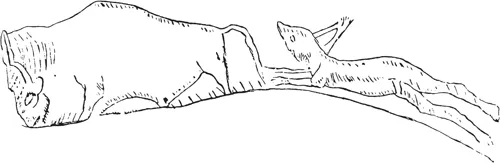

It is impossible to say when the skills of reading and writing first developed for it is very much a question of definition. Attempts to convey thoughts in pictorial form are as old as the earliest known simple paintings, and we could easily surmise that these were preceded by some less permanent medium; marks scratched in sand perhaps or stones allowed to lie in one particular way rather than another (see Figure 1.1).

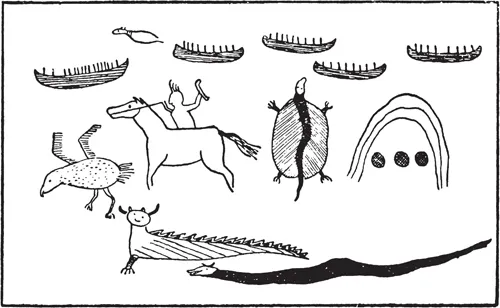

The tracks of prey are, to the hunter, a source of information and hence could be said to be unwittingly ‘written’. The landscape itself – the profile of a hill or the shape of a group of trees – may come to serve as a signal in as much as elements within it are recognized as signs of familiar territory; and it is a small step from noting some natural feature to providing man-made landmarks in the forms of piles of stones, broken branches, marks on the bark of trees or fires lit as points of reference. These too, in a sense, might be said to comprise ‘writing’, if by the term we mean no more than some feature in the environment that conveys information from one person to another. But such a general definition of what constitutes writing is not very helpful. There is no sign, for example, that the simple pictures in Figure 1.1 were intended as anything other than representations of particular events. If, to satisfy a definition of writing, we demand a degree of generality in pictorial representation, so that the same idea is by convention shown by the same picture, this seems in comparison to have been a much more recent intellectual achievement. For example, Figure 1.2 shows a drawing found on the shore of Lake Superior. Five canoes, carrying fifty-one men, went on an expedition lasting three days (three suns). They did well (symbolized by a turtle), rode quickly and were fearless (the eagle). The picture concludes with figures describing force and cunning (a panther and a snake). It is this point, where pictures are employed, agreed between the sender and the receiver as standing for particular ideas, that we might want to mark as the historical origin of reading and writing. What the method and its successors have in common is the desire for a form of communication more durable than speech.

Figure 1.1 An early example of picture writing. This palaeolithic carving is possibly one of the earliest depictions of a scene. It is carved on a piece of antler found at Laugerie Basse, in Auvergne. Source: Taylor, I. (1899) The Alphabet, vol. I, London: Edward Arnold.

If, as Tallyrand remarked, ‘God gave us language that we might conceal our thoughts with speech’, it must be admitted that speech itself as a means of communication has one quite severe limitation: both parties to the interaction must physically be present at the same time as the necessary words are uttered. Further, once spoken, the substance of the message is lost and both parties have only memories of what was said. It is difficult in our culture, dominated as it is by techniques for preserving the substance of communication, to appreciate the social consequences of relying upon speech alone. One of the most obvious however is the great emphasis in pre-literate cultures on developing techniques for reliably transmitting information verbally from one generation to the next. The ‘currency’ of this transmission was, of course, the expression of social, cultural, legal and other ideas. The ‘medium’ was speech itself, but it must not be forgotten that speech is by no means the same thing as thought: it is an event interposed between a stream of conscious awareness and attempts to convey aspects of this to another person. Although its flexibility is very impressive, no one would claim speech as a perfect indicator of thought. Indeed, in some circumstances it is not even particularly good: many of our most significant experiences are, literally, ineffable.

Figure 1.2 A North American rock drawing from Michigan. The drawing describes a successful hunting expedition. Source: Schoolcraft, Henry R. (1851) Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Part I, Philadelphia.

The representation of ideas

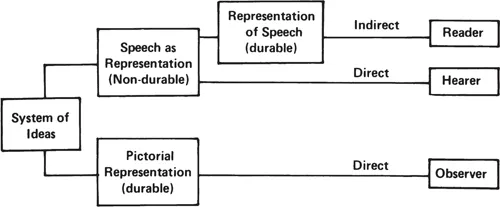

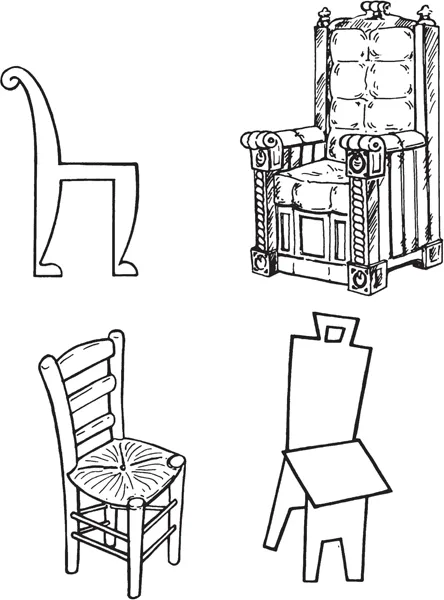

These considerations help to clarify several important distinctions that are a necessary part of an adequate definition of writing. As can be seen in Figure 1.3, we may distinguish between two forms of writing, one which is linked more or less directly to the thoughts and ideas of the writer, and the second which is linked indirectly via the medium of speech. In the first case the written tokens passed from one person to another in the form of pictures are intended to effect an exchange of ideas. In the second case what is transmitted is at best an indication of what might, in other circumstances, have been said. Put this way it may appear paradoxical that the second system (the more indirect) proved to be the more satisfactory, but the reasons for this will soon become apparent. The earliest systems of writing were, in effect, attempts to make durable images of ideas. One might imagine this to be easier for tangible concrete things than for abstract ones. That is, it might seem easier to represent the concept ‘table’ in this way than the concept ‘pride’. However, we should not be misled by this apparent distinction, for to produce pictures at all one must use methods of representation that are conventional to some degree or another. The differences between the images in Figure 1.4 reflect changes, from one culture to another, in what has been thought necessary to set down in order that an observer might have certain predictable thoughts.

Figure 1.3 Speech, pictures and representations of speech as means of symbolizing ideas.

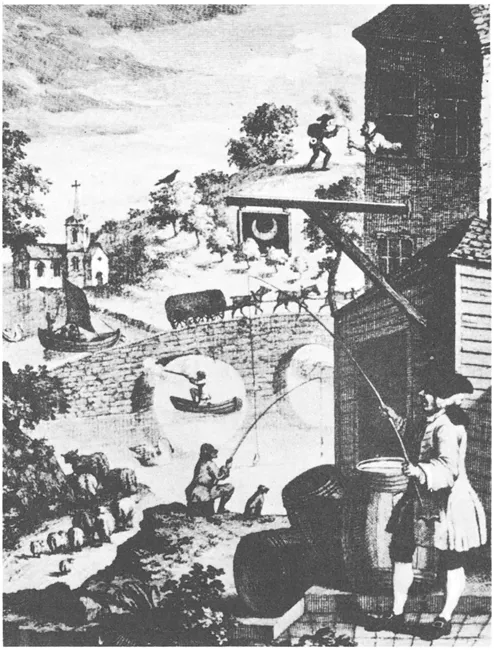

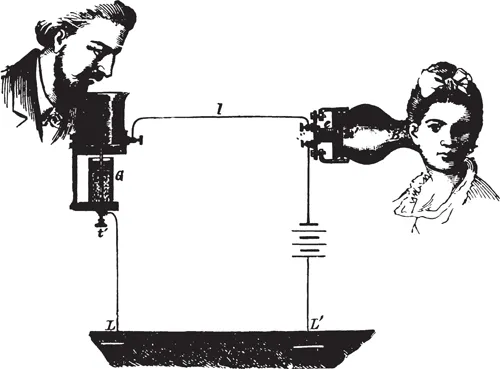

E. H. Gombrich (1965, 1982) has analysed the processes that led to changes in the conventions of drawing. He argues that an effective drawing is one which gives rise to a feeling of recognition. From this point of view the development of naturalistic painting can be charted by the discovery of various techniques for arranging lines and colours so that the observer experiences spontaneous, effortless recognition. The discovery of perspective drawing (see Figure 1.5) is one notable example. However, it appears likely that what is taken as an essential defining element in representations of an object changes in time. We may, in fact, now see some representations as clumsy or unnecessarily realistic or, indeed, obscure (see Figure 1.6); but it is fatuous to demand that there be a single, correct form.

Figure 1.4 Various representations of the concept of a chair. The cultural conventions of Egyptian, medieval and modern society led to changes in the features it was thought necessary to depict and the manner of drawing them.

Figure 1.5 Principles of perspective drawing. Engraving by William Hogarth, 1754.

Figure 1.6 Early drawing of a piece of electrical equipment in which elements are depicted by means of ‘realistic’ representations or more abstract forms relating to their function. Source: Gregory, R. L. (1970) The Intelligent Eye, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. (See also graphical conventions used in Figure 2.1.)

Pictographs

There appears to be a continual shift in pictorial representation which makes distinguishing between the banal and the over-stylized a historical rather than a factual judgement. At any time, for a particular culture, there may have been more or less the same variation in the ability of particular representations to give rise to unstrained recognition. It is this very feature perhaps which posed problems for the direct systems of writing illustrated in Figure 1.3. For example, it is possible to represent the human form by a drawing of a ‘stick man’, illustrating that, for most people in our culture, it is enough to mark the position of the body (though not its shape), and the position and rough extent of the arms and legs for an observer to arrive at a correct interpretation. The overall orientation of the figure on whatever it is drawn can also be used to suggest the position of the person in the ‘real world’ (e.g. it might be upside down), but it would be a mistake to think of

as a symbol for the word ‘man’ – it is, rather, a representation of an idea. It has its origins, not in speech, but in thought, and represents an attempt to portray the concept of man, a concept obviously so rich as to make this representation very feeble.

Early writing systems of the direct kind used such stylized images – known as pictographs – and the technique developed independently in many civilizations in pre-history. Its obvious and grave disadvantage as a form of writing is that there are far more ideas than the repertoire of simple representative pictures. Even the simplest of concepts is too rich, varied and complex to be pinned down in this way. As a means of communication pictographs are only a marginal improvement on gestures; indeed, many captured abstract concepts indirectly by representing, in conventional form, an appropriate gesture. For example, that the gesture of clasped hands means peace has its explanation in the history of combat and arms. It is a conventional way of displaying, within limits, something about the intentions of the person using it (although clearly gestures could also be used to deceive). A drawing of clasped hands may have developed into a more permanent record of the gesture, and come to mean peace. Pictographs take two possible forms: either a drawing of the salient features of some object, or a more metaphorical representation, as in the case of a drawing of a gesture. In either case these conventional signs are not difficult to read. There is a sense in which such simple pictures are instantly available to convey their meaning since the method of representation is what might be termed ‘iconographic’. That is, the relationship between the various features depicted is close enough to the same relationships in the object itself to give rise to instantaneous recognition. Even when greatly simplified, the rules that have been followed are those of graphical convention. Such a method will be effective so long as we agree on the defining features of an object, and these are then presented in an acceptable spatial relationship. In a sense, then, the ‘grammar’ of pictographic representation is already known to all its potential readers: it is defined by the way the world is seen.

The major drawback to pictographic systems of writing will now be apparent. Such drawings do indeed represent concepts directly in the same way that speech does, but with nothing like the power and flexibility of speech, since they are constrained by attributes of the visual world not really relevant to the process of symbolic communication. There are vastly more nuances of thought than could possibly be captured by pictographic means. To write in such a way is to accept similar constraints to those imposed on the scholars in Swift’s fictitious state of Laputa where conversations could only be held by actually transferring objects from one person to another. Even with huge numbers of objects (carried on carts and by overload...