![]()

1

Introduction

Portugal is one of the oldest countries in Western Europe. Its name is derived from the medieval Latin Portucalense, which referred to the territory inland from the Roman town of Portus Cale situated on the mouth of the Douro River. Reconquered from the Moslems in the ninth century, this region was resettled by Christians and administered as a province of the kingdom of Asturias. Because of their country’s isolation, the Portucalense developed a strong sense of individuality, unity, and self-reliance. Cut off from the rest of Asturias, the inhabitants of the province of Portugal, as it came to be called in the vernacular, oriented themselves toward the Atlantic Ocean and the south.

By the middle of the thirteenth century the Portuguese kingdom had achieved Portugal’s present borders as well as a degree of internal political, economic, social, and cultural unity that was well ahead of other European monarchies of the time. This precocious development imparted to the Portuguese a sense of national purpose and a set of centralized political institutions that led them to embark on the great voyages of discovery and eventually to acquire a vast seaborne empire. Stretching from the Americas to the Far East, this empire made the Portuguese crown the richest and most bureaucratic in Europe at the end of the sixteenth century. An oceanic mission had become central to Portugal’s image and definition of its national purpose. Portugal saw itself as a major Atlantic power, as the core of a far-reaching and racially diverse, pan-Lusitanian, global community.

Unlike other European monarchies, the Portuguese crown itself organized and directed the voyages of discovery. This policy retarded the growth of a commercial, entrepreneurial middle class and, at the same time, diverted profits from the overseas trade into sumptuous palaces for the king and aristocracy and cathedrals for the Catholic church. Much of this wealth also flowed through Portugal to northern Europe for the acquisition of manufactures and played no small part in the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain and elsewhere. Thus, early nation-state development and Portugal’s oceanic policy not only exaggerated the authority and power of the traditional, aristocratically based monarchical system but kept Portugal marginal to the process of industrialization and accompanying social change taking place in northern Europe.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, industrialization finally began and a middle class started to emerge. As elsewhere in Europe, as the economic importance of the Portugese middle class grew, its members began to challenge the traditional monarchical system because its political structures prevented middle-class involvement in national affairs commensurate with its sense of economic importance. In Portugal, however, this challenge resulted in an extremely long struggle between the traditional aristocracy and the monarchy that strove to protect the ancien regime and the middle classes that aspired to change it: first, by limiting the crown by a written constitution and, later, by replacing the monarchy with a republic. This struggle waxed and waned for well over 150 years—from the 1820s until the 1970s—during which time the governmental framework of Portugal was structured and restructured as absolute monarchy, constitutional monarchy, republic, and dictatorship. For well over a century, first liberal and then republican political concepts and institutions were in juxtaposition with the traditional values and institutions of monarchical and aristocratic power and privilege.

It can be argued that the golpe ďestado of April 25, 1974, which overturned the authoritarian dictatorship established in 1932 by Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, marks the end of Portugal’s long transition from absolutist monarchy to pluralist democracy. The final transition to democracy did not, however, take place without turmoil. Between 1974 and 1976 a struggle for control of the state ensued among various factions of Portugal’s new political elite. In 1975 Portugal came very close to civil war as these various factions aligned themselves into two camps, each drawing support from regionally based social groups and each mobilized to strike at the other militarily. On November 25, 1975, a group of military officers committed to a Western-European-style pluralist democracy went into action against those who supported a people’s democracy of the Eastern European variant. The officers emerged victorious. This paved the way for the promulgation of a new constitution on April 2, 1976. It also brought to an end Portugal’s oceanic mission and turned the country toward Western Europe.

The promulgation of a democratic constitution, the election of a civilian government on April 25, 1976, and the turn toward Western Europe did not, however, bring stability to Portugal. Conditioned by the struggles of the first two years of political freedom, the constitution represented a truce among warring political parties who were forced to coexist with one another. This resulted in a decade of political bickering and backbiting, no one party able to form a lasting coalition or win an absolute majority at the polls. The support for each of the parties was remarkably uniform from election to election, and it seemed that Portugal’s new democracy was going to follow the Italian pattern. This was not to be: In 1987 the stalemate was broken when a single party won over 50 percent of the vote and an absolute majority of seats in Parliament, which opened a new phase of political stability in Portugal’s democratic development.

This book is a survey of Portugal’s evolution from an absolute monarchy into a nascent pluralist democracy. I do not follow any particular general explanatory approach such as structural-functionalism, class analysis, or world systems theory. Rather, I simply describe the process of Portugal’s political transformation. Yet I do have a point of view: that Portugal, because of its location on the periphery of Western Europe, has historically been in but not of the continent. That is, although the political, economic, and social change in Portugal recapitulates such change elsewhere in Western Europe, the country’s relative isolation, early development as a nation-state, and vast colonial empire retarded the country’s transformation into a modern industrial pluralist democracy.

The plan of the book is as follows: Chapters 2 and 3 provide geographical, social, and cultural background material. Chapter 4 presents the historical context from Portugal’s founding as a nation-state nearly 900 years ago to the collapse of the First Republic in 1910. Chapter 5 discusses the New State dictatorship established by Salazar in 1932. Chapter 6 deals with the golpe d’estado that overturned the New State dictatorship and Chapter 7 with the consolidation of democracy in subsequent years. Chapter 8 examines Portugal’s economic life; Chapter 9 discusses Portugal’s foreign policy and place in the wider world. The tenth and concluding chapter speculates briefly about Portugal’s future.

I have spared the reader footnotes, instead listing at the end of each chapter important works on various aspects of Portugal’s geography, society, history, politics, and foreign policy. Apart from these sources, as well as my own research and periods of residence in Portugal, the book draws on countless conversations with Portuguese, German, British, French, Canadian, and U.S. academics well acquainted with Portugal’s history, society, and politics.

![]()

2

Topography and Climate

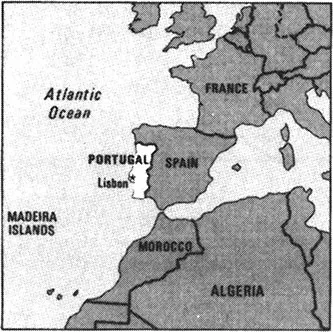

Portugal is a narrow, rectangular country some 350 miles long and between 80 and 140 miles wide. Its 35,516 square miles are not a geographically identifiable portion of the Iberian peninsula, and the frontier with Spain does not, except here and there, follow any distinct geographical feature such as river valley or mountain chain (see Map 2.1). This is so because the border between Spain and Portugal is essentially political, having been defined by Portuguese kings and their Spanish counterparts as they drove southward during the reconquest of the peninsula from the Moslems in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Thus, the various regions of Portugal, although different from one another, correspond to those of Spain: The northeastern part of Portugal is an extension of the Spanish meseta; the area to the south of the Tagus River (Tejo in Portuguese, Tajo in Spanish) is an extension of Spain’s Estremadura; the Serra da Estrela mountains, which traverse central Portugal, are an arm of Spain’s Sierras de Gata, Gredos, and Guardarrama; and Portugal’s two major rivers, the Douro (Duero in Spanish) and the Tejo are also two of Spain’s principal waterways.

Portugal contains considerable physical and climatic diversity. The most striking contrasts in topography and climate are between the region north of the Tejo and the region to the south. The terrain to the north is generally mountainous and moist; rain falls quite evenly throughout the year. The north is verdant and considerably cooler on average than is the south. The Serra da Estrela, Portugal’s highest mountain range (the tallest peak is 6,532 feet), receives quite heavy snows, which frequently block roads and isolate villages. The terrain of the south, except for the extreme south, comprises gently rolling hills and plains. The climate is Mediterranean, with bright sunshine, warm temperatures and low precipitation, except in winter months, when the region is inundated by torrential rains. Summer droughts are common, and water frequently has to be rationed in the major towns. The extreme south has a distinct topography and climate because of its separation from the rest of Portugal by two low ranges of mountains, the Serra do Caldeirao in the east and the Serra de Monchique in the west. Sheltered by these mountains, this region faces the sea, which makes its climate similar to that of North Africa.

Portugal in its regional setting

In order to discuss the various regions in some systematic fashion, it is necessary to say a few words about how Portugal is organized for administrative purposes. Following the French example, Portuguese liberais of the 1830s divided their country into districts (distritos) that continue to the present, the twenty-second and last, the district of Setúbal, having been created in 1926. Eighteen of these districts—Aveiro, Beja, Braga, Bragança, Castelo Branco, Coimbra, Évora, Faro, Guarda, Leiria, Lisboa, Portalegre, Porto, Santarém, Setúbal, Viana do Castelo, Vila Real, and Viseu—are on the mainland. The remaining four are on the Atlantic archipelagoes: The district of Funchal encompasses Madeira and the districts of Angra do Heroísmo, Horta, and Ponta Delgada encompass the Azores. As the boundaries of the mainland districts were not drawn in accordance with homogeneous topographies, an administrative code in 1936, superimposed eleven provinces (provincias) over these districts in an attempt to reintroduce into official life Portugal’s traditional, preliberai administrative regions.

North

The northernmost of these provinces is the Minho, which encompasses the districts of Braga and Viana do Castelo. In the Minho the land rises steeply from a narrow coastal strip, perhaps 5 miles wide, to heights of between 1,000 and 2,000 feet. The eastern boundary of the province is delimited from the province to its west, the Trás-os-Montes, by a series of mountain ranges, the Serras do Gerês, da Cabreira, do Barroso, and do Marão, which form an amphitheater facing the Atlantic Ocean. It was these mountains that isolated the inhabitants of Portucalense from Asturias and oriented them toward the south and the sea, making the Minho the historical cradle of Portugal. The Minho is, as it was in Roman and medieval times, bounded in the north by the Minho River (Miño in Spanish), which for part of its course forms the international frontier between Spain and Portugal. The province receives persistent and copious rainfall (between 80 and 100 inches per year), which makes the region very wet and green and allows it to support the most intensive agriculture in Portugal. The second most densely populated mainland province (503 inhabitants/mi2), the land of the Minho is excessively fragmented into small, family-owned farms, or minifundios, which are the result of ancient settlement patterns, a strong attachment to the land, and the tradition of subdividing land equally among all family members.

The hamlet is the usual settlement pattern, but most Minhotos, as the inhabitants of this province are called, live in individual houses scattered throughout the countryside. Extreme land fragmentation led to a high level of emigration of young single men to Brazil in the 1960s and Western Europe, especially France, in the 1970s, leaving much of the farm work to old men, women, and children. Despite a strong tradition of familial self-reliance, there is much communal cultivation, neighbors and friends frequently conjoining to tend each other’s fields and flocks. Minhotos are the most religious Portuguese, with the rhythm of life turning on the observances of saint’s days and pilgrimages (romarias). These times of communal celebration involve wearing traditional costumes, vigorous dancing, and singing. The Minho is the home of caldo verde, a potato-based soup with shredded kale, a staple of the Portuguese diet, and vinho verde (green wine), a light, sparkling white wine of low alcohol content best drunk well chilled. The Minho contains the town of Guimarães, the capital of Portugal when it was still a province of Asturias, and Barcelos, famed for its ceramic roosters, Portugal’s national symbol.

To the east of the Minho is the province of Trás-os-Montes (literally, behind the mountains), reportedly the poorest region not only in Portugal but in Western Europe as well. Encompassing the districts of Vila Real and Bragança, the Trás-os-Montes, in contrast to the Minho, is arid, rugged, and brown. The province’s aridity is a result of the mountains between the Minho and Trás-os-Montes, which act as a barrier to storms carrying moisture from the west and northeast. The province is sparsely populated (106 inhabitants/mi2); the main economic activity is animal grazing and cereal cultivation. There is also some mining of coal, iron ore, and tin.

The northern half of the Trás-os-Montes, called the terraţria (cold land), has a continental climate of hot summers and extremely cold winters similar to those of the Spanish meseta. The southern half, or terraquente (hot land), is characterized by low, protected valleys with a climate much warmer than that of the high plateau of the terrafria. As in neighboring parts of Spain, in the wilder parts of the province in winter, wolves kill livestock and, upon occasion, small children. Trásmontanos, as the inhabitants of the province are called, are not particularly religious, but they are deeply conservative. There is a clan spirit among some of the families, especially among those living in the terrafria.

The southern edge of the terraquente abuts the Alto Douro (Upper Douro), a region especially noted for its intense cultivation of the port wine grape. The grapes, which are grown in the intricately terraced valley of the Douro, are harvested in late September and early October by migrant labor from the Trás-os-Montes and elsewhere in Portugal. After the wine has been made, it is shipped downriver to Vila Nova de Gaia, on the opposite bank from Porto, where it is matured in the cellars of the numerous port wine lodges, or firms, located there, many of which were established over 300 years ago and have much in common with Spain’s sherry bodegas.

Porto, the industrial and commercial capital of the north, with a population of about 330,000, is Portugal’s second largest city after Lisbon. An ancient city that gave Portugal its name, Porto is a conurbation of n...