eBook - ePub

The Bayonets Of The Republic

Motivation And Tactics In The Army Of Revolutionary France, 179194

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Bayonets Of The Republic

Motivation And Tactics In The Army Of Revolutionary France, 179194

About this book

The Bayonets of the Republic challenges the view of the French revolutionary army as an unskilled but fiercely patriotic fighting force that won simply by overwhelming its enemies with bayonet assaults. Skillfully combining traditional and new military history, Lynn demonstrates that French combat effectiveness encompassed far more than mere patriotism or frenzied charges.Lynn focuses on the Armee du Nord, largest of the eleven armies which protected the borders of France at the height of the Revolution. He does not, however, restrict himself to an analysis of generalship or weaponry, but examines every aspect of life in the French army--from rank-and-file recruitment, officer selection, discipline, political education, and group cohesion, to the flexible use of line, column, and skirmishers on the battlefield. The image which emerges is one of a highly motivated, disciplined, and tactically superior army that outmaneuvered and outfought its opponents.For students of the French Revolution, Bayonets builds upon and extends the best of recent scholarship on subjects as diverse as the debate over conscription and the distribution of revolutionary newspapers and songbooks. For military historians, it combines social, organizational, and operational elements to present a unique view of the French army as an institution and fighting force. And, finally, for social scientists concerned with troop motivation and combat effectiveness, it supplies a highly illustrative case study of troops under fire.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bayonets Of The Republic by John A Lynn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Early Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION ONE

Victory in the North

Chapter 1

The Armée du Nord on Campaign

FEW READERS can be expected to know the history of the Armée du Nord. For most, its triumphs merge into the broad flow of revolutionary events, and its victories belong not to one army but to France. Commanders of the Nord are more likely to stir memories—the comte de Rochambeau, the marquis de Lafayette, Charles François Dumouriez, and Jean Baptiste Jourdan—yet they too are but seldom associated with the army they led. Since analysis requires context, the following narrative history of the Nord introduces the names and events discussed throughout this volume. It joins together in proper sequence elements that will later be dissected for detailed study. It also suggests that the explanation of French victory in the North lies in the citizen-soldiers who made up the Armée du Nord.

Prelude to War

By 1791 the French feared armed intervention by the monarchs of Europe, and after Louis XVI attempted to flee the country in June of that year, war seemed all but inevitable. Yet, in fact, Austria, Prussia, and Russia were far from agreeing on any joint course of action toward revolutionary France. Mutual distrust and the lingering question of Poland's fate precluded them from forming a common front. Despite the lack of a real threat, the French edged toward war, since the most powerful factions in Paris saw war as a servant of their own political aims. But had the French politicians truly understood the weakness of their armed forces, they might not have so lustily voted to declare war against the Hapsburgs on 20 April 1792.

The first two years of the Revolution had greatly weakened the French army. Egalitarian ideas corroded discipline, while the turbulent confusion of the times resulted in a high rate of desertion. A rapid turnover in command, occasioned by the emigration of nearly 60 percent of all officers, struck the army still harder. On 1 January 1791 the National Assembly authorized a peacetime army of 157,000 men, yet the real strength of French forces did not exceed 130,000. After much debate the Assembly voted to shore up the defenses of France by calling up National Guard volunteers. The old regular, or line, army of the ancien régime did not enjoy the full confidence of the legislators. The new volunteer battalions seemed more politically reliable. At first these volunteer battalions constituted only a kind of inactive reserve force, but in the heated session of 21 June 1791, when the Legislative Assembly learned of Louis's flight, they were mobilized to stand alongside the understrength regular army. Volunteers and regulars alike were in need of discipline and training.

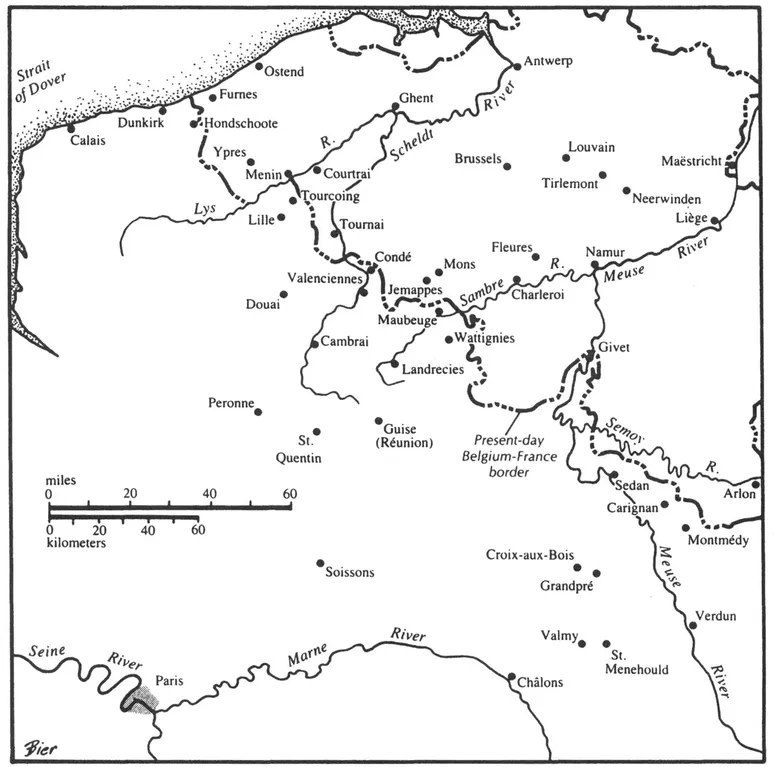

Troops moved up to the frontiers during the summer of 1791, but only in December did the government set up three major armies along France's eastern boarder. Entrusted with the frontier from Landau to Huningue, the Armée du Rhin numbered about 49,000 troops under the command of Marsha] Nicolas, baron Luckner. From Montmedy to Bitche stood the Armée du Centre with about 30,000 men under the marquis de Lafayette. And from the Meuse to the sea the Armée du Nord stretched its nearly 53,000 soldiers commanded by Marshal Jean-Baptiste de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, possibly the ablest officer in the French high command. As the war expanded, enveloping ever more of the French frontier and claiming ever more manpower, the French Republic by mid-1794 would be defended by eleven armies totaling roughly 750,000 men. Throughout the period 1792—94, however, the Nord remained the largest single assemblage of French fighting men.

Early Trials and Setbacks

As soon as war was declared, the government in Paris, pressed by its foreign minister Charles François Dumouriez, ordered Rochambcau to send his ill-trained and inexperienced battalions against a numerically smaller Austrian force in the Austrian Netherlands. The Marshal wisely objected to this unreasonable demand on the basis that even his line units needed more training before they could face the excellent Hapsburg troops, but his objections were overruled. On 28 April General Théobald Dillon led a column of some 2,300 troops from Lille toward Tournai. Meeting a small force of Austrians just across the border, he decided to withdraw the next day, but an orderly retreat proved too much for his soldiers, and they panicked. On 29 April 1792 General Dillon met his death at the hands of his own troops who shouted, "We are betrayed!" and "Every man for himself!" as they fled in utter rout. The same day saw Arrnand-Louis de Gontaut, duc de Biron, depart Valenciennes with some 15,000 men in an

MAP 1. The Campaigns of the Armée du Nord, 1792-94.

attempt to take the fortress of Mons. His command never reached Mons but instead turned back before it got as far as Jemappes. Panic seized Biron's retreating troops just as it had gripped Dillon's, but, fortunately, Biron escaped with his life. These defeats stimulated the Assembly to call for a new levy of volunteers, the Volunteers of 1792. Circumstances confirmed Rochambeau's judgment, but, since the government was reluctant to let him exercise command as he saw fit, he submitted his resignation.

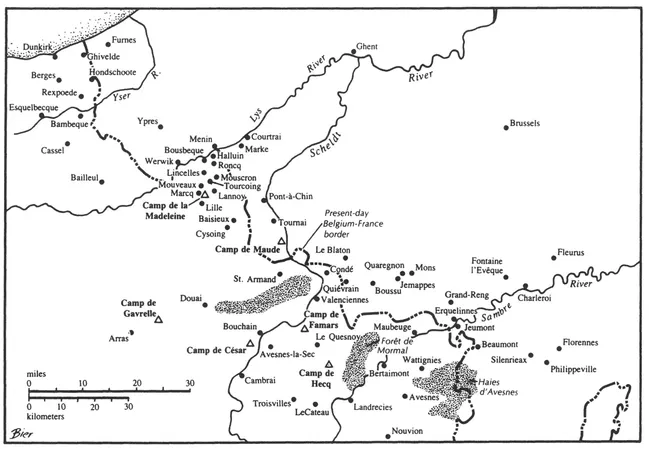

Dumouriez, who virtually rail the Ministry of War as well as foreign affairs, now chose Marshal Luckner, commander of the Armée du Rhin, to replace Rochambeau. The interim command of the Rhin went to General Alexis Magallon, comte de La Morlière. Luckner for some inexplicable reason enjoyed considerable favor with the revolutionaries at this time. The marvelous "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin," known later simply as "La Marseillaise," was even composed in his honor. Yet the fact remained that he possessed only the most mediocre of skills. His military reputation rested on his feats as a daring leader of Hanoverian light cavalry against the French in the Seven Years' War. He arrived at Valenciennes on 15 May, and after less than a month with the Nord, this bumbling septuagenarian led 20,000 troops of his army from the Camp de Famars near Valenciennes on a futile invasion of Flanders. Marching first to Lille, he finally took both Menin and Courtrai on 19 June. But Luckner's timidity in command of an army exceeded his temerity in command of a squadron, and without good reason he withdrew from both towns on 30 June and returned to Lille.

Now occurred a most strange maneuver, the chassé-croisé. Lafayette, first and always a political general, desired to play a greater role in the affairs of government. He reasoned that if his troops were closer to Paris he might rise to become the arbiter of French politics. Consequently, he conspired to switch commands with Luckner, since Luckner's Nord lay closer to Paris than did Lafayette's Centre. Yet while he wished to exchange commands, Lafayette was unwilling to part with the battalions serving under him, because he believed they bore him special loyalty. Consequently, Lafayette proposed that not only the commanders trade places but also that their entire armies switch names and positions. Incredible as it may seem, this insane maneuver received the ministry's approval. The government forced Lafayette to accept only one alteration in his plans. The fallen Dumouriez, who had joined the Armée du Nord on 1 July, used what influence he still had in Paris to win the right to remain with the troops he commanded on the northeast frontier. In charge of the entrenched Camp de Maude, he would cover the frontier while the two armies changed places. In mid-July the actual exchange took place without serious incident.

The turn of events now intervened to give the Nord sttll another commander-in-chief and to provide revolutionary France with a new hero. The threatened Prussian invasion under Karl-Wilheim-Ferdinand, duke of Brunswick, charged the Parisian air with fear and determination. On n July 1792 the Legislative Assembly proclaimed, "Citoyens, la Patrie est en danger." Then on 1 August Paris heard of Brunswick's ill-considered and ill-timed manifesto threatening to destroy Paris should any harm befall Louis XVI. The revolutionary crowd answered this challenge to its bravery and integrity with the revolution of 10 August 1792. Lafayette, a man of the Revolution perhaps, but always a royalist as well, now labored to invest the political capital he had acquired in the chassé-croisé. On 15 August he tried to get his troops at Sedan to take an oath to the king, but he no longer commanded their loyalty. With his army unwilling to march on Paris to restore the king, Lafayette on 19 August crossed the frontier and surrendered himself to the Allies, who imprisoned him for the next five years. Two days before he fled, the Assembly had voted the command of the Nord to Dumouriez.

Dumouriez's Fall Campaigns

Dumouriez could not have been more pleased; he had long advocated an invasion of the Austrian Netherlands, which he could now undertake. He proposed that the best way to stop the Prussian advance would be by an offensive in the north, but the wary Paris government ordered him to bring his army south to defend the capital. This he reluctantly agreed to do, and on i September Dumouriez led the majority of the Nord south from Sedan. At this point begins a rather confusing problem with names. Dumouriez chose to christen the battalions now moving south toward the Argonne the Armée des Ardennes, though in actuality they were only part of the Armée du Nord and not a separate army. The Ardennes was to the Nord as a task force is to a fleet. From September 1792 until June 1794 the Ardennes existed as a separate unit, but it would always be subordinate to the Nord's commander. So closely connected were the two that historians often refer to the Armée du Nord et des Ardennes. The coming months witnessed the creation of two other task force armies, the Armée de la Belgique and the Armée de la Hollande; like the Ardennes they constituted mere subdivisions of the Nord, although unlike the Ardennes they were both defunct by mid-1793.

Dumouriez threw the Armée des Ardennes into the wooded hills of the Argonne in an attempt to bar the Prussian advance on Paris. The Armée des Ardennes displayed unexpected determination and ability for several days, which bought valuable time for the French. But owing to a nearly

MAP 2. The Main Battleground of the Armée du Nord.

fatal instance of confusion, the pass at Croix-aux-bois was left unguarded, and Brunswick's troops were able to seize it on 12 July. The Armée des Ardennes then withdrew toward St. Menehould and a rendezvous with the Armée de Centre, now under the command of General François-Erienne Kellermann. Units of the Ardennes did the best they could, marching and fighting their way south. Combats took place at Grand-Pré on the 15th, at Clermont on the 17th, and elsewhere until Kellermann and Dumouriez finally joined forces on 19 September 1792. The next day Kellermann's troops faced Brunswick's army; Dumouriez's harried and tired battalions stood in reserve. More cannonade than battle, the battle of Valmy stopped the Prussian advance, and, although Brunswick's army was not destroyed, Kellermann gave the Republic a complete strategic victory that day. After more than a week of inactivity, Brunswick began his retreat on 30 September. Dumouriez and the Ardennes had gready aided in the task so well completed by the Centre. Now he could turn his attention once more to the Low Countries.

Dumouriez confided the command of the Armée des Ardennes to General Jean-Baptiste de Timbrune, comte de Valence, and it began its march back to the north. Dumouriez detoured to Paris in order to win support for his plans. He was authorized to attack the Austrian Netherlands, which the French already called Belgium, with the 88-95,000 troops grouped together in his command. To oppose this invasion the Austrians could muster only perhps half that number. No longer the inexperienced and panicky troops of April, these French soldiers who massed along the border displayed a new confidence gained through training and on the battlefield. The men suffered the materiel shortages that would plague the Nord for years, but they were eager to fight. On 3 November Dumouriez set his troops in motion from Valenciennes toward Mons, while he ordered the rest of his command in Lille, Maubeuge, and elsewhere to carry out diversions to occupy Austrian attention. After preliminary skirmishes at Boussu on the 3rd and Quaregnon on the 5th, on the 6th Dumouriez's main body of 30,000 joined by 10,000 Volunteers of 1792 under the command of General Louis -Auguste des Ursins, comte d'Harvilie, formed in order of batde below the town of Jemappes, situated a short distance from Mons. At noon Dumouriez launched his main assault against the 14,000 Austrians holding the heights. In tighriy packed columns his battalions marched direcdy at the enemy. The outcome could not long be in doubt; by two o'clock the Austrians were in retreat, although they had put up an admirable fight. That same day, to the north, other French forces defeated an Austrian detachment at Le Blaton, and on the 7th still other units of the Nord clashed with the Austrians at Halluin. Further victories, however, were unnecessary to establish French control of Belgium—the battle of Jemappes decided the issue.

The Hard Winter and Bitter Spring

French troops now poured into Belgium, Dumouriez himself led what he called the Armée de la Belgique; he delegated the command of the Armée des Ardennes to Valence and the small Armée du Nord first to Anne-François, comte de La Bourdonnaye, and later to Francisco de Miranda. By the end of December the French held Brussels and Liege. But this success had in fact seriously weakened French forces in the Low Countries. Men who had flocked to the tricolor in support of "la Patrie en danger" reasoned that victory, delivering the Republic from its foes, gave them the right to return to their homes. For those who remained with their battalions there was no time for rest, reorganization, and reequipping. Training proved impossible, since the soldiers dispersed into small groups to survive the worst of the winter months as best they could. Had the home government more faithfully and efficiently supplied its victorious troops, perhaps they could have been assembled in large camps where training exercises could have been conducted. For this tired and disorganized army, the worst trials were yet to come. On i February 1793 the Convention declared war on England and on the Dutch Netherlands. Dumouriez then received orders to invade Holland. To undertake this ill-considered attack he assembled a force of some 23,000, new recruits in the main. This army, christened the Armée de la Hollande, advanced toward Antwerp on 16 February. Meanwhile its sister armies were engaged in the siege of Maestricht. All told, the various armies under Dumouriez boasted a paper strength of over 122,000, but in reality this total must be discounted.

On 24 February 1793, the representatives sitting in the National Convention in Paris declared the levy of 300,000 men, but these new recruits would not be assembled and trained in time to help stay the tide of Austrian victories that would soon sweep the French out of Belgium. While the republican troops busied themselves with the siege of Maestricht and the invasion of Holland, the prince of Coburg gathered together an Austrian army of 40,000. On 1 March 1793 this formidable array crossed the Roer River, catching the French by surprise. Dumouricz rushed south, leaving the Armée de la Hollande under General Louis-Charles de La Motte-Ango, marquis de Flers. The French abandoned Maestricht and recoiled back on Louvain. With about 40,000 infantry and 4,500 cavalry Dumouriez resolved to attack Coburg's 30,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry. On 18 March, at Neerwinden, occurred the great battle Dumouricz desired. Considering the poor condition of the French troops, they performed well. On the center arid right they fought the Austrians to a bloody standstill, but the troops under General Miranda on the French left broke and retreated on Tirlemont. After the defeat of Neerwinden, Dumouriez attempted to stand again at Louvain on the 22nd, but by then it was hopeless. To spare the fruitless loss of additional lives and to insure the retreat of his widely scattered forces, Dumouriez negotiated a convention with the enemy. By not contesting the Austrian advance his troops would thems...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- SECTION ONE: Victory in the North

- SECTION THREE: Doctrine, Training, and Tactics

- Appendix: Tables Concerning Tactical Practice

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index