- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Philip Skippon was the third-most senior general in parliament's New Model Army during the British Civil Wars. A veteran of European Protestant armies during the period of the Thirty Years' War and long-serving commander of the London Trained Bands, no other high-ranking parliamentarian enjoyed such a long military career as Skippon. He was an author of religious books, an MP and a senior political figure in the republican and Cromwellian regimes. This is the first book to examine Skippon's career, which is used to shed new light on historical debates surrounding the Civil Wars and understand how military events of this period impacted upon broader political, social and cultural themes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philip Skippon and the British Civil Wars by Ismini Pells in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The English Gentry, Self-Fashioning and the Pursuit of Military Service

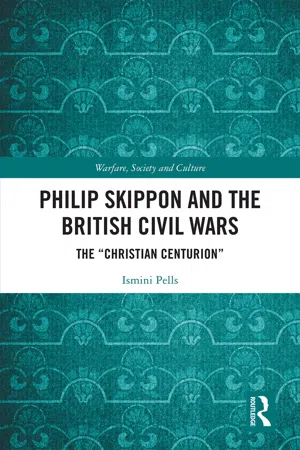

Philip Skippon was born around 1598, the eldest son of Luke Skippon “of West Lexham in the County of norff gent” and his wife Anne (Figure 1.1).1 By styling himself “gent”, Luke Skippon belied his social aspirations. Self-publication of one’s status was vital, for as the seventeenth-century lawyer John Selden observed, whilst a gentleman “‘tis difficult with us to define… in Westminster Hall he is one that is reputed one”.2 There was much confusion over what merited the status of a gentleman: birth, landed income, education, office and behaviour were all means of achieving gentle status.3 Despite differing degrees of gentility and the complex criteria by which families gained admission to the gentle ranks, the gentry were united by their shared interests as landowners and agents of government and by the common claim to bear the name gentlemen.4 Nevertheless, the line dividing the gentry from the rest of society was a “permeable membrane” and “flexible definitions of gentility were a necessary feature of the rather mobile society of early modern England”.5 For those like Philip who were born into the margins of gentility, their access to the gentry’s ideals and privileges set them up for later life but their occupation of the lower echelons of this social group may have made them more status-conscious. This may explain why many took care to cultivate a reputation that highlighted virtues associated with gentility.

Figure 1.1 The Skippon family tree.

The Skippons had lived in Norfolk since at least the fourteenth century but Philip’s grandfather, Bartholomew Skippon, had merely regarded himself as a “yeoman”.6 Defining a yeoman is also a thorny issue. Yeomen fitted into the social strata below the gentry and generally were considered “husbandmen”, tillers of the soil, who were (according to William Harrison in 1577) able to “live wealthilie, keep good houses and travel to get riches” and who played an important, if subordinate, role in local administration.7 Whilst yeoman status was usually conferred upon men who farmed a substantial acrerage, there was no precise norm, which accorded a corresponding diversity in wealth and living standards.8 Nevertheless, the enterprising Bartholomew had seized upon opportunities to build up a sizeable estate and married into a Norfolk gentry family, the Davys of Stanfield.9 Many Norfolk yeoman families had, like Bartholomew, benefitted from the expansion of the land market following the dissolution of the monasteries and sought recognition for their new wealth by claiming one of the essential prerequisites of a gentleman: a coat of arms.10

Interestingly, Philip’s son – also Philip – claimed that the Skippons’ arms (consisting of five golden annulets on a red shield, with the crest of an arm embowed in armour protruding from a ducal coronet and brandishing a sword) had been granted to Bartholomew in 1575.11 Yet there is no evidence of these arms being used by either Bartholomew or Luke. Neither are the arms displayed on Philip’s uncle William’s monument in St Peter’s Church, Tawstock.12 The first recorded use of the Skippon arms was in John Lucas’s manual of the flags and arms of the London Trained Bands captains in 1646.13 Clive Holmes has shown how many of these arms were falsely attributed.14 There was a commonly held perception throughout the Civil Wars that parliamentarians were social inferiors challenging the authority and privileges of the ruling classes.15 Thus, it is possible that Philip connived in the counterfeit claim to arms and fabricated a story about his own family’s grant, which he passed on to his son, in order to overcome social stigma about his comparatively humble social origins and bring respectability to his political stance.

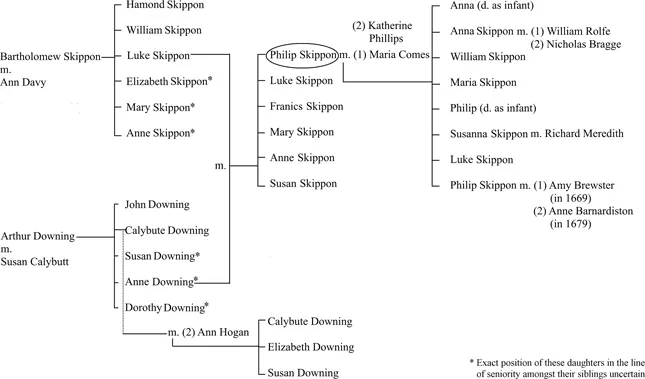

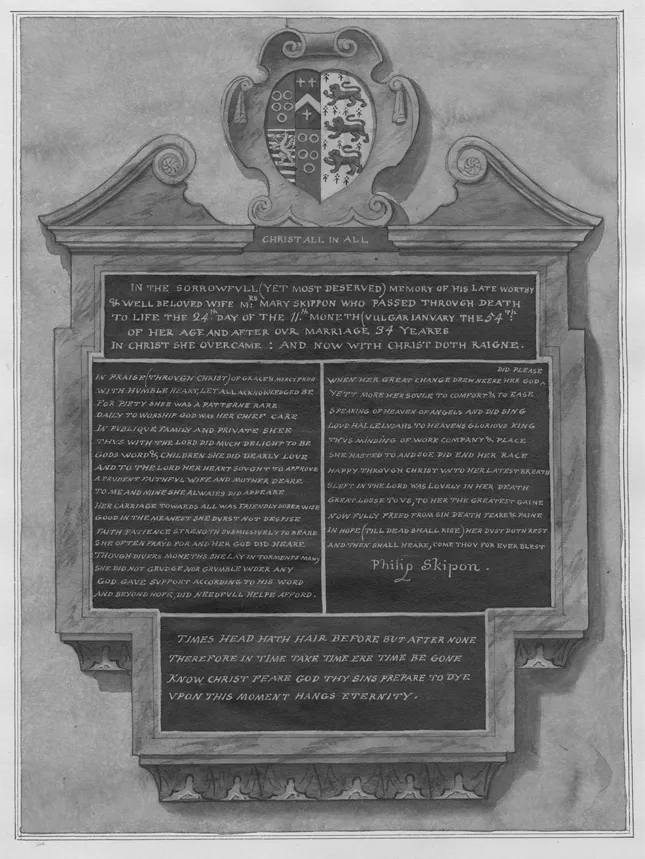

Luke seems to have followed in Bartholomew’s footsteps and endeavoured to cement his social status through marriage. Anne, Philip’s mother, is an enigmatic character. However, the clue to her identity can be found in the coat of arms displayed on Philip’s wife tomb in St Mary’s Church, Acton, which was fortunately recorded for posterity before it went missing (Figure 1.2). On these, the arms belonging to Phillip’s wife were impaled against the Skippon arms, which were quartered to include the arms of Calybutt and Downing, showing that Philip claimed descent from those families.16 Arthur Downing of West Lexham, who died in 1594, married Susan, daughter and co-heir of John Calybutt of Castle Acre. Together they had two sons and three daughters, one of whom was named Anne.17 There is a strong argument, therefore, that Philip’s mother was Anne Downing.18 If this is indeed the case, then this is a significant realisation in the light of later events, as it would mean that the leading puritan clergyman Calybute Downing was Philip’s cousin. Anne’s father was a gentleman of substantial property, who, in addition to being lord of the manor of West Lexham, held further land in West Lexham, East Lexham, Rougham, Dunham Magna, Newton and Castle Acre.19 As the husband of a gentlewoman from a more substantial family and as the son of a gentlewoman himself, Luke may have been more confident than Bartholomew in asserting gentry status.

Figure 1.2 Memorial of Maria/Mary Skippon in Acton Church from a watercolour attributed to Daniel Lysons, 1762–1834 (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.20242).

That said, there is no doubt that in an age when it was noted that “reputation is measured by the acre”, Philip’s family were small fry.20 As the youngest of three surviving sons, Luke could not expect to see much of Bartholomew’s lands and tenements, which were to be passed to each of the brothers and their heirs in turn or sold to raise dowries for Bartholomew’s four unmarried daughters.21 Therefore, in order to make a living, Luke leased the manor of West Lexham from his brother-in-law, John Downing, son and heir of Arthur Downing.22 Following John Downing’s sale of his inheritance to the great English jurist Edward Coke, Luke continued the arrangement with the new owner, for the yearly sum of £58 13s. 9d.23 In addition, over the course of his life, Luke acquired land in his own right. By the time of his death, he owned three enclosures of pasture in nearby Foulsham worth £30 a year, further land in Foulsham worth £12 a year and land in Swaffham to the value of £8 a year.24 Whilst the landed income required to place a man in the gentry category varied from region to region, the evidence suggests that Luke was somewhere near the lower end of the spectrum.25

However, the quality of land in Norfolk meant that the resident gentry did not necessarily have to own vast swathes of land to be deemed worthy of their title. There were numerous small but viable agricultural properties, though this did nothing to assuage the fierce competition for land between the large numbers of emerging gentry families.26 West Lexham was an extensive village in the late sixteenth century, which enjoyed a flourishing economy.27 The soil of north and west Norfolk was perfectly suited to growing grain but its fertility could only be maintained by dunging and treading by sheep. Therefore, farmers developed a “fold course” system, which set aside areas of land, each for arable, pasture and wa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The English Gentry, Self-Fashioning and the Pursuit of Military Service

- 2 Military Culture and Professionalism in the English Regiments in Foreign Service

- 3 Civic Militarism, Religious Idealism and Politics in the City of London

- 4 The Art Militaire of the Civil Wars in Its European Context

- 5 The Experience of Warfare and Martial Culture amongst “Ordinary” Soldiers during the Civil Wars

- 6 Military Victory and Alliances under Strain

- 7 Reconciliation, Reform and the Rump Parliament

- 8 Military and Civilian Government from the Cromwellian Protectorate to the Restoration

- Conclusion: The “Christian Centurion” Reassessed

- Index