- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Concrete is an inherently complex material to produce and an even more complex material to repair. With growing pressure to maintain the built environment, and not simply to demolish and rebuild, the need to repair concrete buildings and other structures is increasing and is expected to become of greater importance in the future.This straightforwar

Information

1 | Understanding Defects, Testing and Inspection |

1.1 Introduction

Concrete, when it first came into use, was hailed as being long-lasting and largely maintenance free. The need for extensive repairs to concrete structures was hardly considered. And, with appropriate design of the concrete, with due recognition of the exposure conditions and a few simple rules in designing the mix and some simple pre-service testing, there is no reason why extended lifetimes for RC structures cannot be enjoyed. However, experience tells us that reinforced concrete is often not the maintenance-free material that some people expect and early failure sometimes ensues. It is worth exploring the reasons for this before proceeding.

Far too often, the basic design of the concrete and attention to detail in its placement are lacking. In the author’s experience, many concrete mixes are not correctly designed and suffer a tendency to bleed and segregate, all of which renders the protection that should be afforded to the steel reinforcement compromised from the start.

Add to that incorrect placement of the steel, with inadequate cover and you have a recipe for early failure, whatever the exposure conditions. In severe conditions, with exposure to marine or de-icing salt, for example, failure can be very rapid indeed. Concrete Society Advice Note 17 (Roberts, 2006) lists some simple rules for good-quality surface finishes for cast-insitu concrete (see next section). Not surprisingly, those same rules will help to provide durable structures when combined with due attention to selection of an appropriate concrete and cover for the exposure conditions it will experience. The author once worked on the old Severn crossing, now replaced by the new bridge. The concrete in this bridge was of such high quality that it had not carbonated at all in 35 years and attempts to demonstrate a Windsor Probe device for strength estimation, caused the pin to simply bounce off, as the concrete was so hard!

There are other reasons why premature failure can occur: in the 1960s, for example, following pressure from the industry to improve formwork stripping times, the cement industry responded by grinding the cement finer and increasing the tricalcium silicate content (C3S) in the cement. Readymix producers were quick to spot that it was now possible to achieve the 28-day design strength with less cement (and therefore a higher water to cement ratio). Whereas, previously, concrete tended to gain in strength significantly after 28 days, with the newer cements that strength gain was much lower. The end result of this was concrete that carbonated rapidly, resulting in the onset of reinforcement corrosion much sooner than expected. There has also been a tendency for contractors to leave the procurement of the concrete to the buying department. Left with a free hand, they will choose the cheapest concrete possible – typically with about a 50 mm slump (S1 consistence). This concrete may be totally unsuitable to place in the works, where a higher workability may well be required, so the temptation to add some water on site to improve placeability is huge. The result, again, is a higher than anticipated water to cement ratio and lower durability. The correct procedure, of course, is to decide on an appropriate set of concretes for the different parts of a contract, with appropriate workability in each case. These can then be called off as required, and the temptation to add water avoided!

Figure 1.1 Zero cover provided to a column in a reinforced concrete car park.

Designers can also improve the chances of a durable structure by avoiding placing drip details directly under a bar (or at least providing additional cover or protection in these areas). Here, the drip groove is placed underneath a horizontal bar, with typically 5–10 mm cover at the top of the groove! The author cannot count the number of times this simple error has been observed on structures during his career!

Another wonderful example of poor durability design is the use of so-called ‘reconstituted stone’ for window mullions and sills. These are made from a semi-dry mortar mix rammed into moulds and usually contain one or more steel rods for handling purposes. An alternative, sometimes found, comprises a rather poorly compacted concrete core, containing the steel rod, with a well-formed attractive stone-like, sandy coloured, mortar facing. Both types have a tendency to carbonate rapidly and corrosion of the steel then ensues with splitting and spalling of the units. Since these are often in use on high-rise structures and offices, the risk of falling material causing injury is high. Indeed, when tackled on this issue, one company, who shall remain nameless, advised the author that carbonation was no longer an issue, because they carbonate the units at the factory! He was of course referring to the other problem that reconstituted stone can suffer – flaking and crumbling of edges and corners, due to inadequate water and compaction in the mix. Carbonating the concrete hardens the surface and thus helps to avoid damaged edges, but compromises the durability of any units containing steel reinforcement, unless this is galvanised or otherwise protected.

Billions of pounds are spent each year on the repair of structures. In the US, alone, for example, annual repair costs are estimated at 18–21 billion USD (source: American Concrete Institute). Getting it right is therefore of critical importance.

In the remainder of this chapter we will explore some simple rules for avoiding problems in the first place and how non-destructive testing (NDT) and semi-destructive tests like coring and lab analysis can pay dividends in avoiding or diagnosing defects.

1.2 Get the Concrete Right

To ensure good-quality, well-finished and inherently durable concrete in the first place, a few simple steps need to be followed.

- The correct quality of concrete, which has been designed to achieve an appropriate strength, durability for the exposure conditions it will experience and ‘finishability’.

- The use of the correct type and quality of form-face material and release agent suitable for the finish specified.

- Workmanship, both in producing the formwork and mixing, placing, compacting and finishing the concrete.

The concrete itself should meet the criteria given in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Guidelines for achieving good surface finish (from Roberts, 2006)

1 | Cement content | Minimum 350 kg/m3 |

2 | Sand content | Not more than twice the cement content |

3 | Total aggregate | Not more than six times the cement content |

4 | Coarse aggregate | For 20 mm max. size – ideally not more than 20% to pass a 10 mm sieve |

5 | Consistence | Not critical, but appropriate for good placement and compaction around the steel |

6 | Water/cement ratio | Normally 0.5 or less |

And, of course, the steel reinforcement should be provided with appropriate cover for the exposure conditions. These seem simple enough, but it is remarkable how often these simple rules are not followed and the concrete is compromised from day one.

1.3 The Role of Non-Destructive Testing

1.3.1 Tests at the Time of Construction

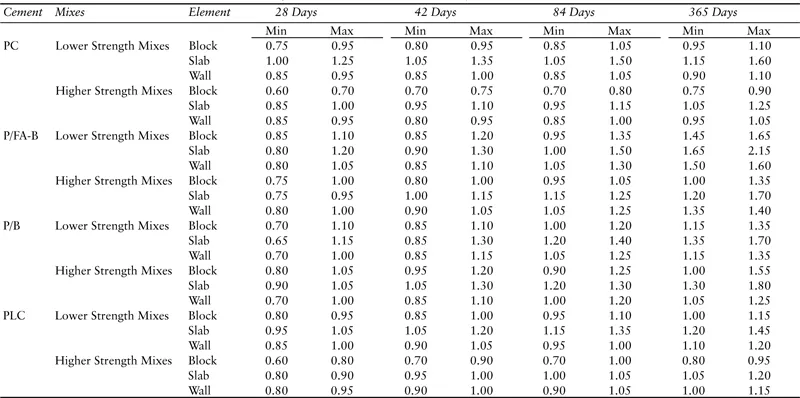

NDT can be used initially at the time of construction to help to ensure that the structure is correctly built with the right materials and the right cover. While cube tests are being conducted, it is entirely possible to carry out some Schmidt hammer tests (Figure 1.2) on the side of the cube prior to loading and support these with some ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) measurements. In this way, a set of reference data for strength against Schmidt hammer and UPV can be built up. If there is any question regarding the quality of concrete in a site component, or maybe just randomly on site, these techniques can then be used to confirm the strength and quality of the concrete, as placed. Far too often, if there is a dispute regarding cube tests or cylinder tests, the engineer will call for core tests to be carried out. The relationship between core tests and cube tests is very complex, depending on the type of member, its curing, the type of concrete, orientation and a range of other factors. Core testing often results in posing more questions than it answers. It is possible using BS EN 13791 (BSI, 2007) and the recently published BS 6089 (BSI, 2010) which offers complementary guidance to BS EN 13791, to estimate the in-situ strength of the concrete in a component. This can be compared with the design strength and a decision can then be made on adequacy of the concrete. In the author’s view, attempting to correlate the core and original cube tests, however, is so fraught with difficulty that it is not recommended. Table 1.2, reproduced from a Concrete Society Technical Report (Concrete Society, 2004), illustrates the problem. The data shows the variability between core and cube strength for the same concrete cast into different types of members, with different cement types, at different ages.

Figure 1.2 Schmidt hammer (courtesy Proceq UK Ltd).

Table 1.2 Variation between core and cube strength in concrete (Concrete Society, 2004)

Apart from establishing that the concrete is of the right quality and that it has been correctly placed, cover to the reinforcement is the next most important parameter. Figure 1.3 illustrates a modern covermeter. Engineers, in the author’s experience, rarely know how to use covermeters and have no idea of the importance of bar size on the results and how misleading cover data can be obtained if the bar size is set incorrectly, or if lapped bars are encountered. These details are covered in the section on covermeters that follows. At the time of construction, it is entirely possible to check that the steel has the appropr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- 1. Understanding defects, testing and inspection

- 2. The petrographic examination of concrete and concrete repairs

- 3. Structural aspects of repair

- 4. Cathodic protection of structures

- 5. Cathodic protection using thermal sprayed metals

- 6. Service life aspects of cathodic protection of concrete structures

- 7. Instrumentation and monitoring of structures

- 8. Electrochemical chloride extraction

- 9. Electrochemical realkalisation

- 10. Corrosion inhibitors

- 11. European standards for concrete repair

- 12. Concrete repair – a contractor’s perspective

- 13. Sprayed concrete for repairing concrete structures

- 14. Durability of concrete repairs

- 15. Service-life modelling for chloride-induced corrosion

- 16. Case studies in the use of FRPs

- 17. Coatings for concrete

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Concrete Repair by Michael G. Grantham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.