- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Subtle Beast: Snakes, from Myth to Medicine introduces you to the complex and absorbing world of these mysterious creatures. Each of the fourteen chapters in this volume can be read independently, but read together they trace a fascinating journey from the macroscopic features of snakes to the molecular description of their venom components.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Subtle Beast by Andre Menez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Men and snakes: truths and fallacies

The good old times, when a well-rounded person might master all aspects of science, seem, alas, to have gone. Science has become such a vast universe, divided into so many apparently strictly separated areas, that it is becoming increasingly difficult to find one topic of interest to everybody, especially if the reader is not seeking a popularised approach.

Undoubtedly, zoology, the biological science of animals, is a privileged domain because everyone has some idea of what it is about. An agreeable discipline, it is usually welcomed by school children, so the basic elements of zoology are absorbed early in life. Moreover, we are surrounded by all sorts of animals, from pets to pests, offering us an immediate opportunity to appreciate and understand animal behaviour. Television, too, is a major source of information with many, often award-winning and popular, natural history documentaries.

Among the different creatures that populate the world around us, snakes occupy a special place; hardly anyone is indifferent to them. They are often beloved, sometimes excessively, or just hated. Most people are strikingly well informed about them; just ask anyone to describe a snake. Back will come the answer that snakes are long animals with no legs, able to crawl on the ground, swim in rivers (people are often unaware of true sea snakes) and climb trees. Most people know that snakes can be poisonous, although this is sometimes a source of confusion as many snakes are rightly recognised as not venomous. It is also common knowledge that snakes periodically shed their skin, from the tip of the snout to the end of the tail.

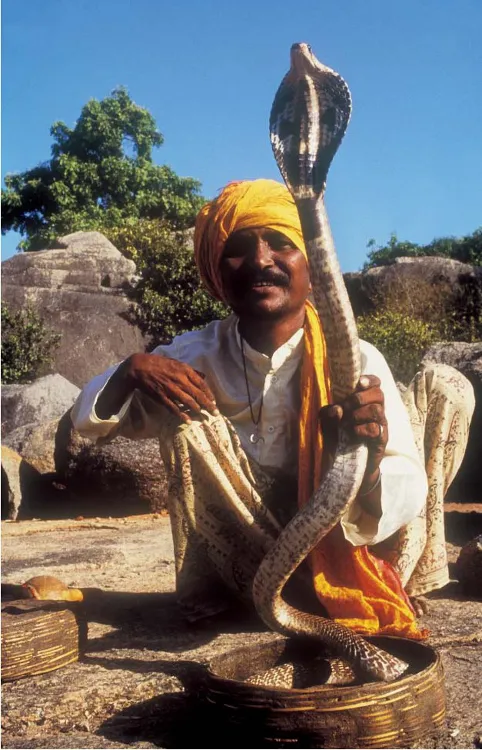

Perhaps even more surprisingly, the specialised names of some snakes are widely familiar. For instance, the one commonly called a ‘viper’ in Europe is a ‘rattlesnake’ in the United States. ‘Cobras’ and ‘Najas’ (Figure 1.1)

mean types of snakes to most people, although they may not remember exactly what they look like. ‘Pythons’ and ‘boas’ are understood not to be venomous but are famous for their ability to coil around their prey, killing it by suffocation or heart failure. People know they are large, although their actual size is often exaggerated. Contrary to common belief, the anaconda is not the largest snake, a title that belongs to the Indian python (Python molurus) which can grow to more than 10 m in length.

mean types of snakes to most people, although they may not remember exactly what they look like. ‘Pythons’ and ‘boas’ are understood not to be venomous but are famous for their ability to coil around their prey, killing it by suffocation or heart failure. People know they are large, although their actual size is often exaggerated. Contrary to common belief, the anaconda is not the largest snake, a title that belongs to the Indian python (Python molurus) which can grow to more than 10 m in length.

Figure 1.1 A snake charmer in India (D. Heuclin).

As we delve deeper, we are frequently confronted by another world, one of fantasies which are endlessly passed on and which often originate from ancient beliefs, legends, myths and even religions. It is fascinating to try to get to grips with what lies behind these misconceptions. Just think of a few common questions, often part of strongly held but misguided beliefs.

Snakes and worms

Are snakes related to worms? Definitely not. Probably because they look similar, and also because they slither, children sometimes confuse the two groups of animals. Interestingly, some historians of the last two centuries are convinced that the same confusion appeared in Bible stories. This is the case for the ‘fiery serpents’ which killed Hebrews crossing regions around the Red Sea on their long journey towards the Promised Land. Travelling along the valley of Arava, between Aqaba and the Dead Sea, on the rocky sea of Suph they met the fiery serpents sent by Yahweh to punish them for complaining of their misfortunes: ‘And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died’ (Numbers 21:6).

Some historians interpret this story as a manifestation of dracunculosis, a disease caused by worms, not snakes. Freshwater lakes and marshes of certain tropical areas, especially in Africa and the Middle East, are known to be infested by filaria, a small endemic roundworm called Dracunculus medinensis. Their larvae are carried by a tiny sort of fresh-water shrimp, no more than a millimetre long, which infects people who drink contaminated water.

It takes about a year of incubation for the worm larva to develop to the adult state. Usually only the disease-causing females can be detected. They are thin animals, 35 cm to 100 cm long (yes, up to a metre!), which migrate towards the outer tissues of the body, punching holes through the skin to release their larvae. Unfortunately, dracunculosis is still present in subtropical areas stretching from the west coast of Africa all the way to India. In 1758, Carolus Linnaeus, the famous Swedish naturalist and physician, gave a scientific description of the adult worm, and in 1871 Aleksej Pavlovich Fedschenko, a Russian zoologist, described its lifecycle.

If we interpret the biblical story of fiery serpents as a manifestation of dracunculosis, we have to assume that the chroniclers of the times confused snakes and worms. But is that really likely? The famous Egyptian medical papyrus discovered around 1870 by Georg Moritz Ebers, a German Egyptologist and novelist, described the disease as early as the fifteenth century BC, reporting that, when a human limb displays a sort of ulceration containing a larva (not yet identified as a worm), the skin should be pierced and the larvae removed gently with pincers. The long and thin whitish matter extracted looked like mouse brain! Plutarch, the famous Greek biographer, quoting Agatharcides, reported that those who travelled around the Red Sea suffered from a strange disease, with small snakes that came out of their bodies and ate their legs and arms. When touched, those snakes burrowed back into the sufferer’s body and hid in their muscles, causing terrible pain. Clearly, a mystery has long surrounded the nature of the ‘creature’ that was responsible for dracunculosis. It was sometimes called the dragonneau, the Pharaoh worm, the filaire of médine or the Guinea worm. An interesting debate continues on whether or not snakes and worms were indeed confused in the past, particularly in the Bible. We shall most probably never know the answer.

Today there is no reason for confusion: snakes are not worms. They have a spinal column, or backbone, and so belong to the category of animals called ‘vertebrates’, a group including fish, amphibians (like frogs, toads and newts), reptiles, birds and mammals. We humans belong to the same broad group as snakes. By contrast, worms are invertebrates without any backbone.

Popular beliefs – most of them wrong

Are snakes really slimy? Quite commonly, even non-poisonous snakes repel people because they are considered to be slimy or ‘gluey’. This is just not true. Reptiles are among the cleanest of animals and it is quite rare to find a ‘dirty’ snake. Why, then, are they thought to be slimy? Perhaps because of the smooth scales which cover their bodies, giving them a shiny appearance and allowing one to slip readily between your fingers if you try to pick it up.

Is a snake capable of hypnotising? Everyone has seen pictures of cobras watching small birds which seem totally paralysed. And we all remember the Walt Disney movie The Jungle Book, based on the famous collection of stories by Rudyard Kipling, which showed Kaa, a huge snake that subjugates Mowgli. However, this fascinating attitude of snakes should not be misinterpreted. Just look at a snake watching its prey. The snake is virtually expressionless – just a steady gaze suggesting profound concentration.

Look closer and you will see that snakes have no eyelids and that the movements of their eyeballs are limited. Moreover, their pupils are large and dark, further adding to the impression of a fixed gaze. Snakes may seem to hypnotise their prey but it is most unlikely that they really do so.

Do snakes love music? Watch a snake charmer playing the flute: the slow movement of the snake, apparently following the musical beat, certainly makes it look as though the animal (usually a cobra chosen for its impressive posture) is an interested listener. But it probably cannot be true because snakes would find it difficult to hear music. While not deaf, their auditory apparatus, and therefore their hearing ability, is limited. Instead, they sense vibrations which reach them through the ground on which they lie and then they rise up, apparently having been woken by the music. Why then do they follow the beat? The snakes are simply trained to follow the movement of the flute in a defensive posture; if the flute was motionless, the cobra would sink back into the basket.

Do snakes really love milk? This belief was, and might well still be, strongly anchored in the minds of many pastoral societies in some countries in Europe and elsewhere. People thought that snakes could suck milk directly from cows, sheep and even from women sleeping near their babies. It was claimed that snakes are so attracted by milk that they approach babies in their cots and take it directly from the infants’ mouths! Not unexpectedly, in times gone by, all sorts of defences were recommended to prevent snakes from approaching a house, a woman or a baby. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, it was thought that the best thing was to carry garlic, which, as some people believe, effectively repels demons. Alternatively, people were advised to carry the heart of a vulture, or wrap themselves in the leaves of an ash tree. Neither the milk-loving behaviour of snakes nor these repellent remedies have been confirmed by zoologists and you won’t find any mention of them in textbooks!

Are ‘minute snakes’, as they are called in French literature, at all dangerous? Again the answer has to be ‘no’. In fact, they got their name from the Latin minutus (small) because they are tiny, not because they could kill a man in a minute. These tiny reptiles, perhaps no more than 15 cm long, are totally harmless to humans (Figure 1.2). They use their heads to dig into the soil and some of them seem to be blind, hence they are called ‘blind-snakes’.

Blind snakes are harmless but, as we shall see later, there are many other snakes, powerful and dangerous, which can indeed kill a healthy man rather rapidly.

Are snakes’ tongues poisonous? This is also a common but once more unfounded belief. Snakes’ tongues are forked (Figure 1.3). They are pushed out through a groove in the front of their mouths, then flicker and briefly touch objects in their immediate vicinity, from which they collect chemicals enabling them to identify the surface they have just licked. The chemical molecules collected by the tongue, as well as those in the air, are carried to a specific organ in the nasal cavity which examines them and reports to the snake’s brain. Tasting is a highly developed function in snakes which allows them to find out whether it is food or something less desirable that has just been tasted. The poison produced by venomous snakes has nothing to do with the tongue; it is injected by long, pointed teeth (fangs), linked to specialised venom-producing glands usually located in the upper jaw behind the eye.

Figure 1.2 Snake or worm? Just a blindsnake: Typhlops vermicularis from Turkey (D.

Heuclin).

Figure 1.3 The tongue of an American crotal, Crotalus viridis (D. Heuclin).

In some countries, including South Africa, there is a common belief that all snakes spit their venom. But once again this is another fallacy. Only a few snakes, such as the African cobra (Naja nigricollis) and the ringhals (Hemachatus haemachatus), spit. They eject a swift thin stream of venom more by squirting than spitting.

Why, at the very end of the twentieth century, are our minds still full of so many erroneous impressions? One possible explanation, but certainly not the only one, is the supernatural roles that snakes have played in human history, and particularly in mythology. Many ancient, fabulous and sacred tales, usually derived from remote religious beliefs, tell us how extraordinary deeds were accomplished by supernatural creatures which were often serpents. Passed down through the millennia from generation to generation, some stories came to us in a confused mixture of truth and legend.

That snakes played fabulous roles in mythology is not surprising. These creatures do such strange things: they move around relatively quickly without legs, manoeuvre well in trees and in water, swallow their prey whole, regularly renew their skin and sometimes inject a highly dangerous poison when they bite. Snakes certainly appear to be so very different, both from other animals and from ourselves, that it is easy to see why, until the relatively recent advent of rigorous scientific investigation, these reptiles were regarded almost as supernatural creatures.

2

Snakes and myths

Scientific books on snakes frequently include a chapter describing the part they have played in myths. The descriptions often correspond to ancient poetic visions; they remind us that many (and often excessive) virtues have been ascribed to serpents: strength, power, beauty, cleverness, nimbleness, a highly developed instinct, nobility and an ability to cause death. Snakes in stories were described as supernatural and, in myths, were thought to be devils or gods.

Being sometimes poisonous, hidden in the shadows, slowly and mutely gliding, snakes have often been deemed powerful and shifty, evil creatures whose major aim was to frustrate the natural and proper development of life. Sages speculated endlessly about the negative impact of serpents on such essential matters as the creation of the universe, the fate of human beings and of their gods. Just take a look at a few examples of how the literature through the ages has portrayed snakes and serpents.

In the Bible, the Devil assumed the form of a serpent and successfully persuaded Eve to pick fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, the only tree in the Garden of Eden which God had strictly forbidden her to approach. Eve’s action resulted in the loss of the privileges God had given to people: their punishment was the obligation to work, to beget offspring and to die. Snakes also had to pay the price for their imposture; they were condemned forever to crawl and, for those with a biblical tradition, to be the symbol of vice and lewdness.

The word Ouroboros is of Greek origin. It is the image of the snake that bites its own tail, so adopting a circular shape. It symbolises the perpetual continuity of life and death, both fertilising and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Men and Snakes: Truths and Fallacies

- 2. Snakes and Myths

- 3. Snakes and Early Medicine

- 4. The Origin of Snakes

- 5. What Are Snakes?

- 6. Classification of Snakes

- 7. Discovery of Snake Venoms

- 8. Snake Venom Potency

- 9. Clinical Aspects of Snake Poisoning

- 10. Non-Toxic Venom Components

- 11. What Are Snake Toxins?

- 12. Toxins In Action

- 13. Stopping the Action of Toxins

- 14. From Toxins to Drugs

- Appendix: A Taste of Protein Chemistry

- Bibliography