eBook - ePub

Available until 26 Feb |Learn more

Learning First, Technology Second in Practice

New Strategies, Research and Tools for Student Success

This book is available to read until 26th February, 2026

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 26 Feb |Learn more

Learning First, Technology Second in Practice

New Strategies, Research and Tools for Student Success

About this book

Building on the bestselling Learning First, Technology Second, this book helps teachers choose technology tools and instructional strategies based on an understanding of how students learn.

After observing teachers and students interact with technology over many years, Liz Kolb began to wonder: While students' attention levels are high when they use digital devices, how can we move them to an equally high level of commitment to their learning tasks? Her extensive research into this question led to the development of the Triple E Framework, in which the learning goal—not the tool—is the most important element of a given lesson.

With this understanding, this book extends the ideas from Learning First, Technology Second, offering:

After observing teachers and students interact with technology over many years, Liz Kolb began to wonder: While students' attention levels are high when they use digital devices, how can we move them to an equally high level of commitment to their learning tasks? Her extensive research into this question led to the development of the Triple E Framework, in which the learning goal—not the tool—is the most important element of a given lesson.

With this understanding, this book extends the ideas from Learning First, Technology Second, offering:

- An overview of the popular and highly regarded Triple E Framework.

- A compelling myth vs. reality format through which to apply the research and strategies tied to the Triple E Framework.

- A step-by-step process for instructional designers and tech coaches to use the framework with classroom teachers for better lesson design.

- Twelve authentic lessons designed by K-12 teachers to meet all three elements of the Triple E Framework, with suggestions on how to improve lessons with technology.

- Examples of how two schools have systematically integrated the framework across their district.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Learning First, Technology Second in Practice by Liz Kolb in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Debunking Myths with Research That Informs the Triple E Framework

THIS CHAPTER GRAPPLES WITH some of the common myths that have arisen in recent education narratives around what it means to engage, enhance, and extend learning through technology. By citing and explaining research studies that seek to clarify the reality behind these myths, the chapter will explore:

Engagement Myths. Screen time, 1:1 with digital devices, and multitasking with technology

Enhancement Myths. Quantity versus quality of technology use, effectiveness of educational applications, underserved students and technology, adaptive software and learning, and digital versus analog

Extension Myth. Technology as a teacher replacement, interactive technology use to build soft skills in students

By understanding the current research behind what is effective and ineffective when using technology to engage, enhance, and extend learning, you will be able to make better pedagogical choices when using the Triple E Framework Evaluation Rubric and, ultimately, create lessons with technology tools that better meet the needs of your learners. The end of this chapter includes some takeaway recommendations on how you can integrate these research-based practices into your own practice when teaching with technology.

Engagement Myths and Realities

According to the Triple E Framework, engaging students in learning with technology tools means:

• The technology should allow students to focus on the learning task, assignment, or activity with less distraction (time on task).

• The technology should help motivate students to start the learning process.

• The technology should cause a shift in the behavior of the students, where they move from passive to active social learners (co-use or co-engagement).

Engagement: Screen Time

MYTH: The type of screen time makes little difference when it comes to students engaging in learning activities with media.

REALITY: There are different types of screen time, and certain types can be more beneficial to engaging students in learning goals.

Often parents and educators try to employ rules around screen time, and commonly these involve a time limit (e.g., two hours a day). While extreme prolonged hours of media or screen time (over ten hours a day for adolescents) can have a negative effect on student achievement, the type of screen time, rather than the amount, is often a better way to determine if students will learn from the screen. Research into different types of screen use has found that the type a child is engaging with can determine the potential benefit or harm (“Screen Time and Young Children,” 2017). Thus, time should be less of a factor in screen use than the type of screen use. Understanding the different types of screen use can be useful when deciding when and how to allow students to engage with screens in the classroom.

To further complicate matters, media and researchers often send mixed messages about screen time. For example, we hear that playing video games can lead to attention problems, yet playing video games can also help children develop problem-solving skills. Likewise, engaging with social media can lead to depression, yet it can also give students access to people and information that can help their academic careers. The key is understanding how to support students in using screen time that is academically or socially beneficial while also knowing when it is purely for entertainment and could possibly become excessive.

Studies are exploring medical concerns for students who excessively use screens (more than five hours a day), such as depression, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidal thoughts and attempts, particularly in girls (Twenge et al., 2017). Links have been found between media multitasking—such as texting, social networking, and rapidly switching among smartphone-based apps—and lower gray-matter volume in the brain’s anterior cingulate cortex, a region involved in emotion processing and decision-making (Heid, 2017). There have also been links discovered between an increase in dopamine and using social media, which could drive compulsive device use and give teenagers feelings of distraction, fatigue, or irritability when they are separated from their phones (Heid, 2017).

Knowing that there are potential harms in screen use, it is important to understand there can also be benefits for children’s learning. According to research conducted by Guernsey and Levine (2017), learning can occur with media and younger children when considerations for the three Cs of content, context, and the child are clear and developmentally appropriate. As far as the content of the screens, TV shows and movies made specifically with high-quality educational content and a “just right” pace can improve children’s basic academic skills. Thus, the features of the show (content, editing, pace) will also impact the educational outcome (Kostyrka-Allchrone et al., 2017). Therefore, passively watching a show could be beneficial, if it is made with educational content and with a pace appropriate for the age of the child.

A recent study of young children found that interactivity when using screens supports children’s executive functioning (Huber et al., 2018). Children are more likely to delay gratification after interactively playing an educational app than after passively viewing a cartoon, YouTube video, or TV show. In instances where a child was purposefully interactive, the child’s working memory improved after playing the interactive educational app (Huber et al., 2018). Other studies have also found benefit to children who interactively used screens for their learning, in particular when the interactivity is explicitly connected to the learning goal, such as dragging an object to fit a particular end goal versus randomly tapping on objects (Pitchford, 2018; Russo-Johnson et al., 2017).

Two considerations should be made when exposing students to screens in learning: activity level and educational content level. First, when considering the activity level, teachers should ask, “How interactive is the media?” Is it asking students to critically think and engage with the media (e.g., making purposeful taps or swipes to meet goals, responding to critical-thinking questions, or creating a response)? Does a show pause for students to respond? Second, when considering the educational content level, teachers should ask, “Is the media using high-quality educational content (based on research)?” Is it providing realistic information related to the learning goal, or is it filled with advertisements, inconsistencies, or a “Hollywood version” of reality? Is the pace of the show appropriate for the age of the child, so they can easily comprehend all the information being shared?

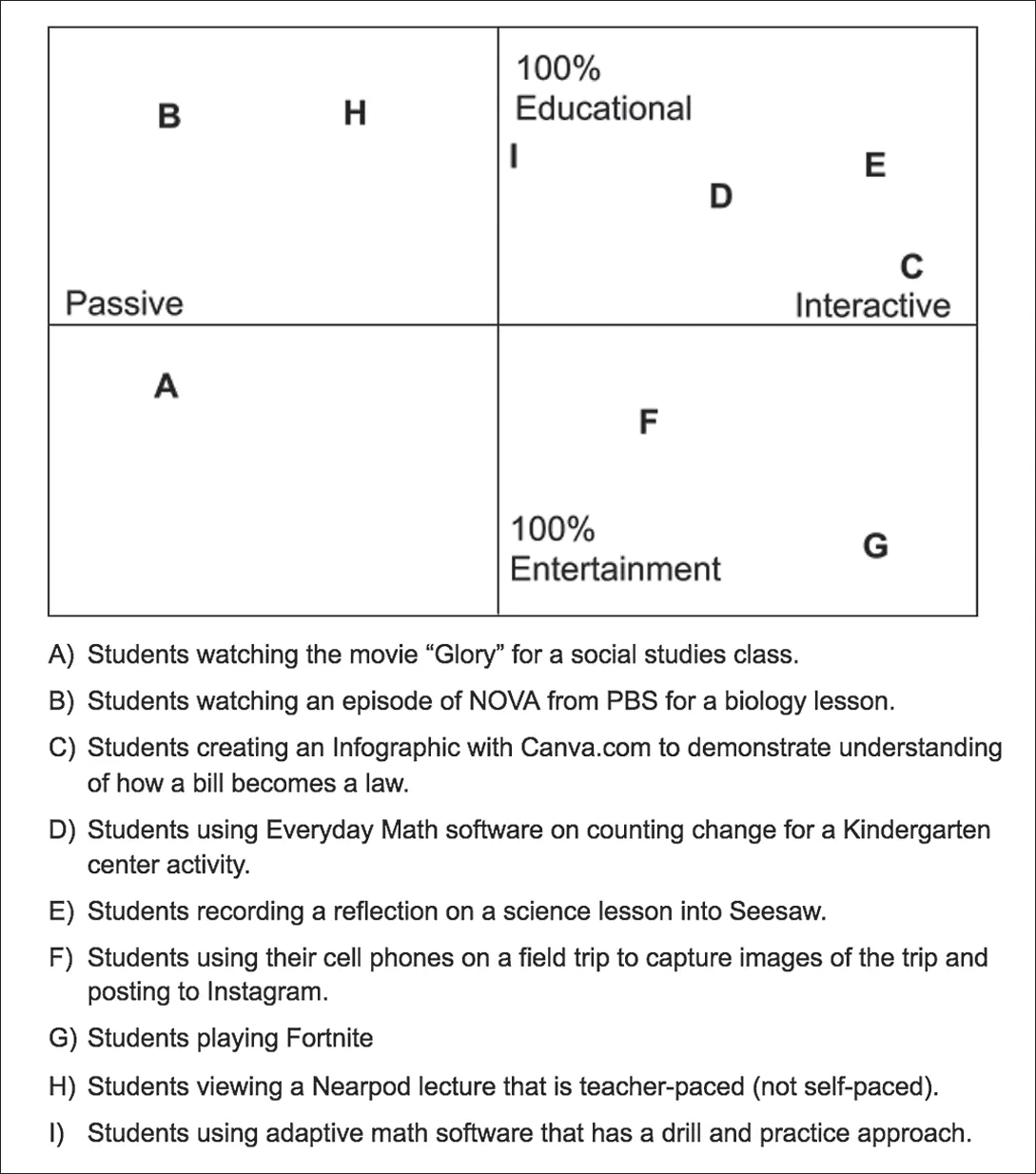

How Research Reality Impacts Your Teaching Practices

The chart in Figure 1.1 can help you evaluate the activity and educational content levels of a piece of screen media. The X-axis of the chart represents the activity level and ranges from passive to interactive. At the passive end (left), students are passively watching a screen or mindlessly swiping/tapping to the next item to view without a clear educational/learning goal in mind. On the interactive end of the scale, students are “minds on” and physically engaging with the technology or application. For example, students are purposefully selecting objectives or tapping based on a particular goal. Students are getting thoughtful feedback (computer or human) on their activity. The Y-axis of the chart represents the educational content level ranging from entertainment (bottom) to educational. At the lowest level, the media is focused on entertaining and does not have a particular educational goal built into the media. It may also include advertisements or other distractions. On the educational end of the scale, the media is focused on educational goals, and it does not have advertisements or distractions from the learning goal. Each element supports and scaffolds students to understand a particular piece of content or learning goal.

Ultimately, the best screen choices for a positive learning outcome are the ones that end up with high educational-interactivity levels (far right side). However, a screen choice that lands as passive-education or interactive-entertainment could be supported as positive screen time by the teacher creating high-quality instructional supports around the screen time.

Figure 1.1 Charting the educational and interactive levels of different types of screen time.

Engagement: 1:1 Access

MYTH: 1:1 access to devices is the most effective way to assure positive student learning outcomes.

REALITY: 1:1 access to devices does not guarantee better student learning outcomes.

There is often pressure on K–12 schools to have 1:1 access, where every child has their own device. In schools that are 1:1, the children often have digital devices with them at all times, even when they are not essential for the activities of the day—the belief being that if children have ubiquitous, uninterrupted access to digital tools, they will be able to always engage with their device to gather and construct knowledge 24-7. Although in theory, 1:1 sounds beneficial for creating mindful digital learners, research is mixed on the benefits of students having ubiquitous access to devices throughout the school day. For example, comparing achievement scores of students from Baltimore County Schools, which began a 1:1 program in 2014, and Baltimore City Schools, which does not have a 1:1 program, reveals an unanticipated trend: Over the past few years, Baltimore City Schools students’ scores have increased more (Bowie, 2018). Baltimore County Schools spent 147 million dollars on a 1:1 laptop rollout in hopes of addressing both equitable access and achievement. While they have alleviated some of the digital access issues, the overall achievement outcomes have been less than desirable. The achievement scores have stayed stagnant for students in Grades 3 through 8, despite them having laptops for three straight years (Bowie, 2018).

Other concerns have arisen in 1:1 schools, as well. In Baltimore County Schools, for instance, teachers have reported frequent inappropriate use of devices in 1:1 programs (Bowie, 2018). Parents have expressed concern that devices are often used to do educational drill-and-practice games, rather than higher-level learning. In addition, because 1:1 programs are so costly, there is concern that money is being siphoned away from other essential academic programs and needs (such as more t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About ISTE

- About the Author

- Contents

- Introduction: Evolution of the Triple E Framework

- Chapter 1: Debunking Myths with Research That Informs the Triple E Framework

- Chapter 2: A Deep Dive into Engagement

- Chapter 3: A Deep Dive into Enhancement

- Chapter 4: A Deep Dive into Extension

- Chapter 5: Meeting the Three Es: Authentic Lessons from K–12 Educators

- Chapter 6: The Triple E Coaching Tool for Tech Coaches and Instructional Designers

- Chapter 7: District-Wide Approach to Integrating the Triple E Framework

- Appendix A: Elements of a High-Quality Application Based on the Triple E Framework

- Appendix B: Resources to Deepen Your Knowledge of the ISTE Standards

- References

- Index

- Back Cover