- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Brutal State of Affairs analyses the transition from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe and challenges Rhodesian mythology. The story of the BSAP, where white and black officers were forced into a situation not of their own making, is critically examined. The liberation war in Rhodesia might never have happened but for the ascendency of the Rhodesian Front, prevailing racist attitudes, and the rise of white nationalists who thought their cause just. Blinded by nationalist fervour and the reassuring words of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and army commanders, the Smith government disregarded the advice of its intelligence services to reach a settlement before it was too late. By 1979, the Rhodesians were staring into the abyss, and the war was drawing to a close. Salisbury was virtually encircled, and guerrilla numbers continued to grow. A Brutal State of Affairs examines the Rhodesian legacy, the remarkable parallels of history, and suggests that Smithís Rhodesian template for rule has, in many instances, been assiduously applied by Mugabe and his successors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Brutal State of Affairs by Henrik Ellert,Malcolm Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

– 1 –

A Prelude to Rhodesia

Africa is still lying ready for us. It is our duty to take it. Cecil John Rhodes

This prelude to the story of Rhodesia provides a summary of the main events that took place in the country from the time white settlers established themselves in the 1890s when the territory was annexed by the British South Africa Company (BSAC). It is designed to place the unfolding narrative in a historical context. In particular, it notes the central role of the BSAC and its successor, the British South Africa Police (BSAP). It will explain how the settlers were initially welcomed as friendly traders but quickly came into conflict with the indigenous people when they realised that these settlers were here to stay. Their rebellion against the occupation of their lands came to be known as the First Chimurenga. However, superior firepower and modern technology put an end to their resistance and cleared the way for a rapidly increasing number of white settlers, with the British government granting the colony self-government under white rule in 1923. In the chapters that follow, we trace the events that led to the Second Chimurenga and the end of colonial rule in 1980, focusing on the Rhodesians’ efforts to retain power.1

On 11 November 1965, the Rhodesian government made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI), severing its ties with Britain, and the future was far from certain. Under the banner of the Rhodesian Front (RF), the white nationalists gained nothing from this move; in fact, it came to mark the beginning of the end. While most Rhodesians welcomed the event on that day, it truly was a ‘great betrayal’ of everything that the previous generations had wrought, and it led to a civil war that destroyed the lives of thousands. At several anniversaries celebrating UDI, Prime Minister Ian Smith would sound the independence bell, but initial euphoria slowly gave way to a hollow clanging of despair.

Although the settler Pioneer Column, put together in South Africa by Cecil John Rhodes, arrived in 1890, it was not the first time that the region had experienced foreign claims upon its soil. Portuguese-speaking traders had come to the area, then known as the Kingdom of Monomotapa, in the sixteenth century in search of gold and ivory, travelling as far as the Munyati river and Chief Mashayamombe’s land, and their quest for even greater shares saw them interfere in local politics, playing one faction off against another in order to gain advantage. The Portuguese traders were expelled in 1694 by a Rozvi–Mutapa alliance that included ancestors of Chief Makoni of Maungwe, who would fight against the whites in 1896.

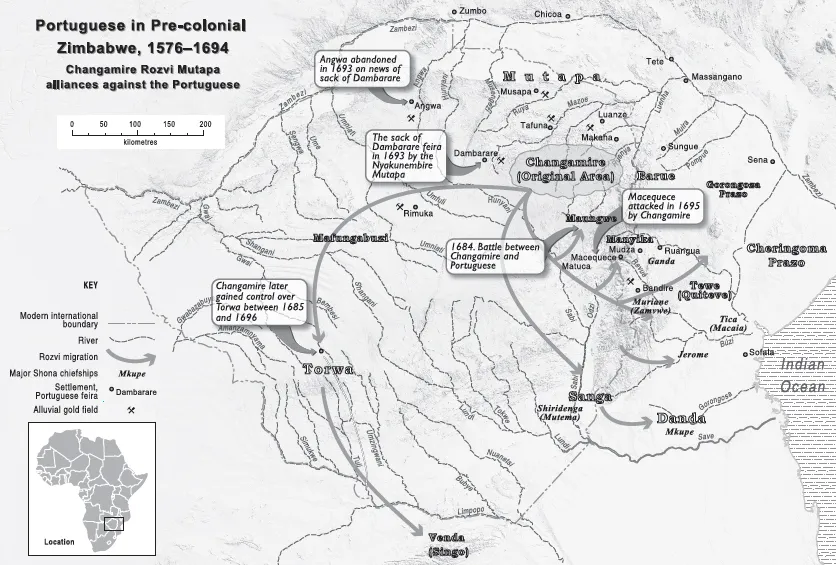

The Portuguese presence in pre-colonial Zimbabwe, 1576–1694

During the period 1576 to 1694, Portuguese-speaking traders known as Muzungu established a series of trading settlements – feiras – close to the major alluvial-gold-producing rivers in north-eastern Zimbabwe. They brought useful trade goods, and successive rulers of the Mutapa dynasty acquiesced to the gradual encroachment of the foreigners who slowly consolidated their commercial interests and control of gold-producing areas.

In 1684 a Portuguese expeditionary force under Caetano de Melo e Castro headed for Maungwe (Makoni) from Macequece, intending to counter a threat to their commercial interests posed during the expansionist Changamire Rozvi migrations. The Portuguese were forced to withdraw to Macequece (east of Umtali), where their settlement was later attacked by Changamire force in 1695. Although Changamire Rozvi posed a threat to the Mutapa Nyakunembire, they were united in a common resentment of the Portuguese.

This period of Portuguese occupation ended after the destruction of their major feira at Dambarare (near Mazoe) in 1693/94, when the traders and Dominican priests were attacked and killed by allied Mutapa Nyakunembire and Changamire Rozvi forces. Traders at Musapa (Mount Darwin) and Ongwe (Angwa river) feiras heard news of this and headed to Tete in Mozambique. From the eighteenth century onwards, a new era of commerce evolved when traders from Macequece and Tete visited to buy gold.

It was only in the late nineteenth century that the Portuguese cast their eyes upon Zimbabwe’s riches once more. At the forefront of this move was Manuel António de Sousa who, like his trader forebears, forged careful treaties with Shona chiefs. De Sousa – or Gouveia, as he is better known – is one of the most significant figures in the history of nineteenth-century central Mozambique. A Goanese Christian Indian, he came to Mozambique in 1853 after abandoning his studies to become a priest. He was indeed cut out for a different life: a hunter, trader and warlord, he held sway over the vast tract of land that is now the Manicaland province of Zimbabwe. His trading interests coincided with Portuguese territorial designs during the ‘scramble for Africa’ in the 1880s.

The Europeans were naturally hostile to Gouveia, largely because he posed a threat to their own ambitions and supplied Shona chiefs with guns. Between 1860 and 1890, he expanded his trade across the border into modern-day Manicaland and Mashonaland. At each trading settlement he took a local wife, paid lobola (bride price) and appointed her as his local agent. His children were many and his surname passed down through Shona family genealogy. Gouveia’s genes, his aura of power, his armed militia and his supply of guns are still part of the oral traditions of many important Shona families. Bloodlines are ongoing: Constantino Gouveia Chiwenga, for example – who, as commander of Zimbabwe’s defence forces, oversaw the November 2017 coup in Operation Restore Legacy that toppled Robert Mugabe – is a blood descendant via the Svosve chiefship that fiercely opposed the whites in 1896/97.

The Shona were initially beguiled by the arrival of the white people from the south, seeing it as a further opportunity for the trade that they had hitherto enjoyed with the Portuguese who had come from the east. They thought these new ‘Muzungus’ would likewise leave after buying their gold. However, whereas the Portuguese had ‘paid’ for the alluvial gold with rifles and cloth, these new whites wanted to mine the gold themselves. The animosity this created saw history repeating itself, for this was precisely why the Portuguese had been driven from the Zimbabwean goldfields in 1693/94.

Treaties and concessions

In the mid-nineteenth century, many years before the wave of British settlers arrived, the missionary Robert ‘Moshete’ Moffat established an advisory relationship with Mzilikazi, the first Ndebele king. Mzilikazi was a lieutenant of Shaka, the Zulu king, but he rebelled against him in the 1820s following a dispute over cattle. He fled northwards and settled in what is now Limpopo province (formerly the Northern Transvaal) near Phokeng and Mosega (Zeerust) and adopted a scorched-earth policy characterised by murder and devastation on a grand scale that came to be known as the Mfecane. Between 1836 and 1838, following a series of confrontations with the Voortrekkers that ended with the Battle of Mosega, he fled northwards across the Limpopo and settled in the region now known as Matabeleland, controlled by the Kalanga people whom he assimilated. He then created a military system based on regimental kraals similar to that of the King Shaka, strong enough to repel attacks by the Boers.2

Moffat’s son, John, went to work for Cecil Rhodes and negotiated treaties that paved the way for British occupation and conquest. Given this background, Mzilikazi naturally considered John’s character to be flawless. However, Moffat would fully exploit old ‘family ties’ with Mzilikazi and later persuade his successor, Lobengula, to sign what came to be known as the Moffat Treaty, in which he affirmed his friendship with Britain and undertook not to enter into any agreement with any other state or party. Striking while the political iron was hot, Rhodes sent his partner, Charles Rudd, his secretary, Francis Thompson, and Rochfort Maguire, a lawyer, to Lobengula in August 1888 to secure territorial rights at all costs.

On 30 October 1888, Lobengula affixed a mark to a document, the ‘Rudd Concession’, that he scarcely understood. As it was written in English, Lobengula – who was, in any case, illiterate – had to depend upon interpreters to explain its contents. That any king would concede ‘the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals situated in my kingdom’ in return for cash, rifles and, astonishing as it may seem, an armed steamboat, is inconceivable; had he truly been informed of the document’s import, he would have refused to sign. In fact, when the implications of the Concession became clear, Lobengula tried to repudiate it on two occasions, but to no avail.

Rhodes formed the BSAC and obtained a Royal Charter through Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister, to colonise Mashonaland. Although the Company secured wide authority to pass laws, grant land, make treaties and acquire new concessions, its ability to do so was supposedly contingent upon subject chiefs in various areas conceding the appropriate powers. In practice, the BSAC paid this detail scant regard. John Mackenzie of the London Missionary Society, at the time based at Kuruman in the Northern Cape, was incensed by the BSAC charter and wrote a letter to the British government, urging it to shoulder its responsibilities:

It would be a mistake of the gravest character for Her Majesty’s Government, in view of certain difficulties in Matabeleland, to divest itself of duties specially devolving upon it as the supreme power in South Africa, and to impose these duties on a mercantile company. In taking such a step Her Majesty’s Government would have all the disadvantages and unpopularity of shirking responsibilities; while, of course, in the end, when serious difficulties arose, it would find that responsibility really and truly had never creased to rest on its shoulders; and that the British Government could only escape that responsibility by abdicating its position and leaving South Africa.3

Many years later, following the Rhodesian Front’s UDI, Mackenzie’s words proved true when ‘Her Majesty’s Government’, in terms of the Southern Rhodesia Act of 1965 [Chapter 76], again became the supreme power in Rhodesia. Mackenzie was also clearly apprehensive about the northward trajectory of gold-diggers and speculators:

If there is any lesson taught us by the past history of South Africa, it is that this northward rush of the white men is irresistible. Governments can and ought to guide it and control it; they cannot stop it; and on the whole it is not for the interest of any class that it should be stopped.4

Edward Lippert, a German adventurer, deceitfully acquired land rights from King Lobengula in 1889 for a hundred years. He subsequently agreed to sell this ‘Lippert Concession’ to the BSAC, which was a coup for Rhodes as the Rudd Concession related only to mining rights. The Ndebele remained unaware of the full implications of this agreement – described by the Missionary John Mackenzie as ‘palpably immoral’ – until 1892, by which time it was too late.

Occupation and resistance

On 13 September 1890, Lieutenant Edward Carey Tyndale-Biscoe raised the Union flag in what would later be named Cecil Square – and, after Independence, Africa Unity Square – marking the arrival of the Pioneer Column. The Pioneer Column, with its BSAC Police escort, had begun its march from the Tuli river towards Mashonaland on 11 July 1890. In overall command of the whole expedition was Lieutenant Colonel Edward G. Pennefather of the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoon Guards, who had been appointed by Sir Henry Loch, the British High Commissioner for Southern Africa. Loch was of the opinion that a military man should command the Column. It arrived in Fort Salisbury on 12 September 1890 and, on the next day, the flag-raising ceremony was held.

The initial occupation of Mashonaland led to an influx of settlers, prospectors and miners, who skirted Matabeleland to avoid contact with Lobengula’s impis (Ndebele warriors). This was inevitable, as it would have been impossible to imagine either Rhodes or Lobengula accommodating each other peacefully. However, in July 1893 incidents in Fort Victoria (Masvingo) were a catalyst for confrontation. First, the copper telegraph wire – so useful for making ornaments – being strung towards Fort Victoria was stolen by local Shona villagers. Then came the collective punishments imposed by Captain Charles Frederick Lendy, in this case a fine in the form of Shona cattle that Lobengula claimed were his. Despite Lendy warning him of the consequences of so doing, Lobengula dispatched 2,500 of his warriors to Fort Victoria. On 9 July 1893, the white population woke to find the impis killing Shona men and women, burning villages and stealing cattle. Who fired the first shot after Lendy and thirty-eight mounted men rode out from the fort is unclear, but the ensuing skirmish resulted in the deaths of thirty warriors, including Mgandani, the King’s nephew.

At this critical moment in Rhodes’s imperialist career, he met Leander Starr Jameson, a London-trained physician, at Kimberley, South Africa. Jameson had quickly acquired a sound reputation and his patient list included President Paul Kruger and Lobengula. In some ways, this unusual friendship was not entirely unexpected, for Jameson inspired devotion from his contemporaries, and people attached themselves to him with extraordinary fervour. Jameson put his relationship with Lobengula to good use: it enabled him to persuade the King to grant Rhodes’s agents the concessions that led to the formation of the BSAC. In 1890, three years before the outbreak of violence at Fort Victoria, Jameson closed his medical practice and joined the Pioneer expedition, binding his fortunes to Rhodes’s schemes in the north.

On 18 July 1893 Jameson drew up a plan to deal with Lobengula – in response to his attack on Fort Victoria – and instructed Major Patrick Forbes to raise a force of volunteers in Salisbury to advance on Bulawayo, supported by columns from Fort Victoria and Fort Tuli. Two major engagements occurred during the march to Bulawayo on the Shangani and Bembesi (Mbembesi) rivers. Forbes had ensured that the column had enough wagons to form a laager that, with practice, could be achieved in three minutes. Together with the Maxim gun, the balance of p...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword and Acknowledgements

- About the authors

- 1 A Prelude to Rhodesia

- 2 The Rhodesians

- 3 The Shaping of Rhodesian Society

- 4 Surviving Sanctions under UDI

- 5 The Rise of Black Nationalism

- 6 The Armed Struggle, 1972–1977

- 7 The British South Africa Police

- 8 The Central Intelligence Organisation

- 9 The Selous Scouts

- 10 The South Africans

- 11 Mozambique

- 12 Rhodesia’s External Operations

- 13 Approaching the Final Hours

- 14 High Jinks and Low Morals: The Media War

- 15 Rhodes’s People

- Bibliography

- Index