eBook - ePub

Along the Silk Roads in Mongol Eurasia

Generals, Merchants, and Intellectuals

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Along the Silk Roads in Mongol Eurasia

Generals, Merchants, and Intellectuals

About this book

During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Chinggis Khan and his heirs established the largest contiguous empire in the history of the world, extending from Korea to Hungary and from Iraq, Tibet, and Burma to Siberia. Ruling over roughly two thirds of the Old World, the Mongol Empire enabled people, ideas, and objects to traverse immense geographical and cultural boundaries. Along the Silk Roads in Mongol Eurasia reveals the individual stories of three key groups of people—military commanders, merchants, and intellectuals—from across Eurasia. These annotated biographies bring to the fore a compelling picture of the Mongol Empire from a wide range of historical sources in multiple languages, providing important insights into a period unique for its rapid and far-reaching transformations.

Read together or separately, they offer the perfect starting point for any discussion of the Mongol Empire’s impact on China, the Muslim world, and the West and illustrate the scale, diversity, and creativity of the cross-cultural exchange along the continental and maritime Silk Roads.

Features and Benefits:

Read together or separately, they offer the perfect starting point for any discussion of the Mongol Empire’s impact on China, the Muslim world, and the West and illustrate the scale, diversity, and creativity of the cross-cultural exchange along the continental and maritime Silk Roads.

Features and Benefits:

- Synthesizes historical information from Chinese, Arabic, Persian, and Latin sources that are otherwise inaccessible to English-speaking audiences.

- Presents in an accessible manner individual life stories that serve as a springboard for discussing themes such as military expansion, cross-cultural contacts, migration, conversion, gender, diplomacy, transregional commercial networks, and more.

- Each chapter includes a bibliography to assist students and instructors seeking to further explore the individuals and topics discussed.

- Informative maps, images, and tables throughout the volume supplement each biography.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

Generals

CHAPTER 1

Guo Kan

Military Exchanges between China and the Middle East

FLORENCE HODOUS

Guo Kan (1217–77) was a Chinese general who took part in the Mongol campaigns in Central and Western Asia and participated in the Mongol conquest of Baghdad in 1258. He led the mangonel engineers, Chinese specialists in siege warfare, who were instrumental in the Mongol armies’ success. While legendary feats and victories over Muslim and Christian kingdoms in the Middle East are further ascribed to Guo Kan, the general appears to have returned to China after the Mongol victory in Baghdad. Back home, he served in a military capacity under Qubilai Qa’an (r. 1260–94), founder of the Yuan dynasty. Guo Kan’s journey offers the opportunity to explore not only the transfer of military experts and warfare technologies across Mongol Eurasia but also speaks to the role that material artifacts played in Chinese imaginations of the Middle East and Europe, as well as to the expansion of Chinese knowledge on their geography and politics.

A WORTHY DESCENDANT

Our sole source on Guo Kan is his biography in the Yuanshi or the History of the Yuan Dynasty.1 There are no references to him in the Persian sources, making it impossible to corroborate details about Guo Kan’s military feats in the Islamic world. Still, we can draw an outline of Guo Kan’s life and career and compare it with other sources on the Mongols’ campaigns.2 Since Guo Kan’s Yuanshi biography was compiled years after his death, it is also valuable for exploring how later Chinese authors envisioned their relationship with and involvement in the Mongol westward expansion.

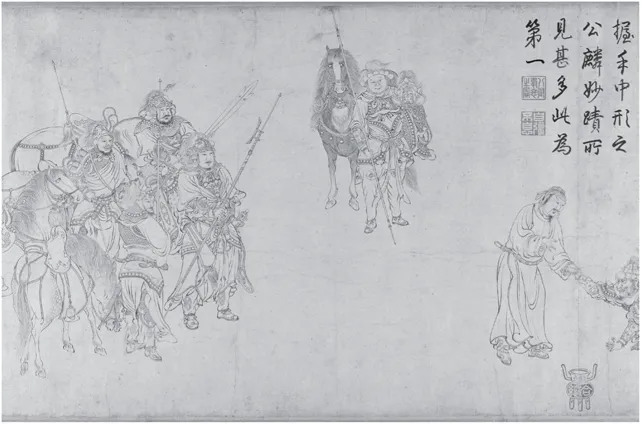

As his biography in the Yuanshi points out already at its opening, Guo Kan was a descendant of Guo Ziyi (697–781), a famous general of China’s Tang dynasty (618–907). In addition to quelling the An Lushan rebellion (755–63),3 Ziyi took part in several campaigns against the Tibetans and the Uighurs.4 Two traditional enemies (and occasionally allies) of the Tang dynasty, the Tibetans and the Uighurs would both later submit to the Mongols. Guo Kan’s next known ancestors are his grandfather, Guo Baoyu, and his father, Dehai, both of whom were also generals mainly active in the Chinese western frontiers in Central Asia and further west (see fig. 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1. Guo Ziyi Receiving the Homage of the Uighurs, Li Gonglin (eleventh century). Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Although six centuries lapsed between the Tang general Ziyi and Guo Kan’s grandfather Guo Baoyu, the latter was likewise born and raised in Ziyi’s hometown Huazhou (in today’s Shaanxi province). Unlike Ziyi, however, Guo Baoyu seems to have been a rather minor mingghan commander (head of a unit of a thousand) under the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), in charge of defending Dingzhou (nowadays southwestern Hebei). As soon as Chinggis Khan’s general Muqali (1170–1223) and his forces advanced to northern China, Guo Baoyu defected, enlisting with the new Mongol overlords.5

Muqali then took the defector Baoyu to see Chinggis Khan, whom Baoyu impressed with his practical and bold advice. Receiving the post of general command officer of artillerymen,6 he accompanied Muqali on his campaign to subdue the Jin dynasty. More importantly for his future as well as for the prospects of his descendants, he managed to forge a close personal relationship with Chinggis Khan. His biography gives a vivid account of Baoyu’s injury during Chinggis Khan’s campaign against the Qara-Khitai (1124–1218) and Muḥammad Khwārazmshāh (r. 1200–20) in Central Asia: “Baoyu was hit in the chest with an arrow, so the Emperor [Chinggis Khan] ordered to cut open the belly of a cow and place him inside it, and in a short while he recovered.”7 The biography goes on to claim prodigious feats for him. It recounts how Baoyu quickly returned to battle after his injury and accepted the submission of the city of Beshbaliq (in north Xinjiang), before crossing the Jaxartes river to take Samarqand (modern-day Uzbekistan), and then crossing the Oxus River to advance until Merv (modern-day Turkmenistan).8

Baoyu is furthermore presented as instrumental in bringing Chinese inventions to the battlefield. The biography mentions that at the Oxus, he used huojian, literally “fire arrows,” against the enemy ships. Scholars have debated how to identify these “fire arrows.” By then, the Mongols had already encountered gunpowder weapons, particularly in the form of explosive gunpowder bombs, in their wars against the Jin in northern China. The presence of Chinese engineers such as Guo Kan in the Mongol armies conquering the West has led to the speculation that the Mongols may have imported such weapons into Western Asia.9 However, there is insufficient evidence to support this conclusion. It is more likely that the fire-arrows Baoyu introduced were not rockets, but arrows carrying incendiary charges.10 They may well have been an innovation from China, albeit falling short of being true gunpowder weapons.

In any case, in 1220–23, Guo Baoyu participated together with his son Dehai in the famous campaign of Chinggis Khan’s generals Jebe (d. 1223) and Sübe’etei (1175–1248), which circled the Caspian Sea and returned back to Mongolia via Russia and the Qipchaq Steppe. Dehai’s biography follows his father’s in the same chapter of the Yuanshi, and though the section on Dehai is very short, it nevertheless records that he quelled the rebellions of a Tibetan and an Uighur commander, just as his ancestor the Tang general Ziyi had fought centuries earlier with Tibetans and Uighurs. Dehai further contributed to the campaign against the Jin dynasty until his death from a battle wound in 1234.11 Baoyu and his son, though not quite as famous or central to their dynasty, nevertheless exceeded the accomplishments of Ziyi in terms of their geographical reach; and Dehai’s son Guo Kan was to do even more.

GUO KAN THE ARTILLERYMAN (CHAQMAQ)

Guo Kan was seventeen years old when his father died. Through the mediation of his father and grandfather, he was already well regarded by major figures of the Yuan dynasty, and the great general Shi Tianze (1202–75) himself hosted him in his house and educated him. At the age of twenty, he was appointed commander of a hundred, and accompanied Sübe’etei, and later Tianze himself, on campaign, rising to leader of a thousand.

Like his grandfather, he participated in a campaign to the west, this time the campaign led by Chinggis Khan’s grandson Hülegü (1218–65), brother of the reigning Qa’an Möngke (r. 1251–59). Hülegü’s campaign set out in 1253 and culminated in the establishment of the Ilkhanate and direct Mongol rule in the realm of greater Iran. The material contribution of Chinese personnel to the siege warfare on this campaign has been well documented.12 According to the Yuanshi: “In the year guichou [1253] the army [i.e., the vanguard commanded by Kitbuqa (d. 1260)] reached the realm of Munaixi [the realm of the so-called Assassins].13 . . . Guo Kan defeated the army of fifty thousand soldiers, took 128 cities, and decapitated it...

Table of contents

- Imprint

- Subvention

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Dates and Transliterations

- Introduction

- Part One. Generals

- Part Two. Merchants

- Part Three. Intellectuals

- Glossary

- Chronology

- List of Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Along the Silk Roads in Mongol Eurasia by Michal Biran, Prof. Dr. Michal Biran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.