![]()

1

Formative Assessment and Science

when teachers are given the statement “When I think of assessment, I think of …” they almost always complete the statement with the word “testing.” This view of assessment results, in part, from beliefs and practices that stem from text-driven curricula where students study content in a chapter and then are given publisher-provided assessments in the form of multiple-choice, matching, or true/false items related to the content in the chapter. Questions often require students to select a response that was memorized or match terms to definitions. These classroom assessments are used to determine student learning and reward them for learning specific information within a specified time and in a particular way.

Views of classroom assessment are also influenced by the practice of using standardized tests to measure and communicate learning. Levels of performance on summative assessments are communicated through scores or grades that are often more important to students than the knowledge or skills they learned.

NEW WAYS OF THINKING ABOUT ASSESSMENT

In recent years the leaders in the assessment field have made serious attempts to explain the significant differences between assessments of learning and assessments for learning (Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, & Wiliam, 2004; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Marzano, 2000; Marzano & Kendall, 2007; Stiggins, 2002; Stiggins & Chappuis, 2006). Understanding this distinction requires a shift from thinking about assessment as a way of determining what students have learned following instruction or as a capstone performance to determine a score or grade to thinking about assessment as part of instruction intended to capture evidence of student learning for purposes of monitoring progress and guiding and improving instruction.

A first step in changing perceptions of assessment requires taking a critical look at assessment as a practice that has, essentially, three different purposes:

- Preassessments: Preassessments are administered to students at the beginning of an instructional unit to identify prior knowledge or misconceptions they may have about a topic. Such information determines a reasonable starting point for instruction.

- Formative assessments: Formative assessments are used throughout instruction to collect evidence of learning for purposes of monitoring progress and guiding instruction.

- Summative assessments: Summative assessments generally take the form of paper-and-pencil tests, capstone performances, or a combination of the two, which follow instruction and are used to:

- determine how well students “measure up” to a standard

- compare students to one another and designate positions

- assign grades

Assessments for learning serve a very different purpose than preassessments or summative assessments since their purpose is to provide meaningful feedback to teachers and students about student progress in reaching important learning goals. Scores on assessments for learning are used to inform, not to factor into a grade.

The information provided through formative assessments is used to monitor progress and direct students toward continued learning, relearning, or alternative learning to improve motivation and self-esteem. Reaping the rewards of formative assessment requires not only a shift in practice, but a different way of thinking about effective teaching and learning altogether.

GOAL-CENTERED ASSESSMENT

Formative assessment is goal centered; that is, it focuses attention on successful teaching and learning of important learning goals and standards. This approach involves students in the teaching/learning process and offers opportunities for them to take responsibility for learning by setting personal goals and selecting strategies for meaningful learning. Through formative assessment, students compete with themselves rather than with other students.

A comprehensive view of classroom assessment is offered by Stiggins (1994). His principled view of classroom assessment points to the need for classroom teachers to be able to define and assess five kinds of learning goals—knowledge, reasoning, skills, product, and affective goals. This view of assessment aligns well with the broad range of goals and standards for science education, as well as other areas of the curriculum.

The goal-centered view of assessment challenges teachers to use assessments throughout learning to:

- monitor student progress in conceptual understanding and knowledge and use of skills

- capture evidence of thinking, reasoning, and problem-solving ability

- apply concepts and skills to technology and society through projects, products, and inventions

- provide information about the student’s ability to work with others, communicate his or her ideas and understandings, show respect for living things, and demonstrate other dispositions.

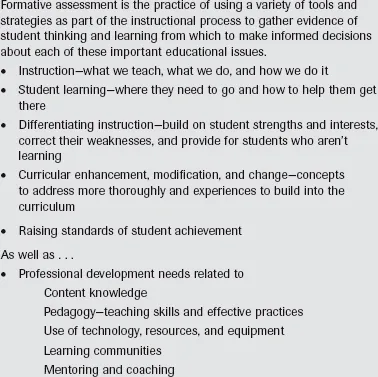

Formative assessments capture evidence of student thinking and learning related to important concepts, skills, and habits of mind. Data and information gathered through formative assessments also inform curricular change and professional development needs. A comprehensive definition of formative assessment is offered in Figure 1.1.

RESEARCH SUPPORT FOR FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT

Educational research sends powerful messages to practitioners about what works to enhance student achievement. In their landmark study, Black and Wiliam (1998) surveyed over 580 articles and chapters in an effort to determine if improving formative assessment raises standards. The researchers found overwhelming evidence to support the fact that formative assessment is one of the most powerful tools for promoting effective learning. They also discovered that “improved formative assessment helps low achievers more than other students and so reduces the range of achievement while raising achievement overall” (p. 141).

Black and Wiliam (1998) also showed that achievement gains are greater when teachers involve students in the assessment process. They contend that students need to be trained in self-assessment in order to have a greater understanding of important learning goals and understand what they need to do to achieve success (p. 144). Thus, an essential component of formative assessment is student self-assessment.

Kohn (1999) described self-assessment as teachers and students working together to determine the criteria by which their learning will be assessed and having them do as much of the actual assessment as is practical. He contended that the process is less punitive, gives students control over their education, and provides enormous intellectual benefits (p. 209).

Kohn also cited studies that showed positive results when students were given choices, were involved in decision-making, and felt personally responsible for their learning. Studies reported that students completed more tasks in less time, improved self-esteem and perceived academic competence, and developed higher-level reading skills (pp. 222–223).

Figure 1.1 A Comprehensive View of Formative Assessment

In his study, How Teaching Matters, Wenglinsky (2000) linked classroom practices to academic performance in math and science using data from questionnaires to parents, teachers, and over seven thousand eighth-grade students who took the 1996 National Assessment of Educational Progress. Besides identifying characteristics of effective teachers, the study pointed to effective practices, one of which was implementing teacher-developed assessments into their lessons to provide frequent feedback to students about their learning.

Other studies focused on identifying policies and practices that define high-quality teaching and promote learning (Anderson & Stewart, 1997; Black et al., 2004; Ermeling, 2005; Stronge, 2002; Weiss, Pasley, Smith, Banilower, & Heck, 2003). These studies reported that effective teachers encourage interactions among students and between students and teachers and use assessment as a learning tool to provide frequent, constructive feedback to students and to monitor student progress.

Reeves (2008) contended that when grading practices improve, discipline and morale improve as well. He found remarkable changes in one challenging urban high school through focused attention on improved feedback and intervention for students. Positive changes included reduction in course failures, increase in enrollments in advanced placement courses, decline in suspensions, and a noticeable improvement in teacher morale and school climate.

The instructional power of formative assessment is echoed in the well-known meta-analysis of effective instructional strategies led by Marzano, Pickering, and Pollock (2001), which identified providing feedback—a central principle of formative assessment—as one of nine categories of instructional strategies that have statistically significant effects on student achievement.

Marzano and his colleagues offered a quote from researcher John Hattie as saying, “The most powerful single modification that enhances achievement is feedback” (Marzano et al., 2001, p. 96).

Further support for the use of formative assessment in both the learner-centered and knowledge-centered classrooms is provided by the National Research Council: “An important feature of the assessment-centered classroom is assessment that supports learning by providing students with opportunities to review and improve their thinking” (NRC, 2005, p. 16).

The National Science Teachers Association offered a number of research-based position statements that describe the organization’s stand on critical issues related to science education, including the role of assessment. The position statements help to guide administrators and teachers in the design and implementation of a curriculum that addresses important science goals and standards. The position statements can be viewed at http://www.nsta.org/position.

CREATING A VISION FOR FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT

There is a body of firm evidence that formative assessment is an essential component of classroom work and that its development can raise standards of achievement. We know of no other way of raising standards for which such a strong prima facie case can be made. Our plea is that national and state policy makers will grasp this opportunity and take the lead in this direction.

—Black & Wiliam, 1998 (p. 147)

In an ideal world, all students would learn and be successful. Educators are well aware that there are many variables that influence student achievement. Yet many of the significant variables that determine what students will learn and how students will learn operate within the classroom setting. With the abundance of research on effective teaching and formative assessment, we know with certainty that the teacher is the key to student learning and that formative assessment is a powerful tool for promoting higher achievement.

In that teaching and assessment are so closely intertwined, the journey toward the use of formative assessment as a tool for increasing student achievement requires us to think critically and thoughtfully about each of these important issues.

- Schoolwide and personal beliefs and practices related to learning and assessment

- Traditional versus student-centered views of teaching and assessment

- Characteristics of effective formative assessment programs

EXAMINING BELIEFS AND PRACTICES

Our beliefs strongly influence our practices. There are understandings and misunderstandings associated with the term “assessment.” The ways that teachers view student learning and their beliefs about the purposes of assessment will determine, to a great extent, how they teach and assess in their classrooms.

Clarifying beliefs and practices related to assessment is a first step in creating a vision for the design and implementation of formative assessment tools and strategies in the classroom. Black and Wiliam (1998) contend that the most important difficulties with assessment revolve around three issues: effective learning, ...