![]()

CHAPTER 1

Finding Equity

If equality guarantees equal access for students when they enter school, then equity guarantees equal results when students exit school. For over fifty years, equality of entrance has guaranteed that any student—Black, Brown, rich, poor—can attend the public school where they live. But troubling and persistent achievement inequity according to race, economics, and language clearly illustrate that no equality of academic success has been systemically achieved. According to DeCuir and Dixson (2004),

In seeking equality rather than equity, the processes, structures, and ideologies that justify inequity are not addressed and dismantled. Remedies based on equality assume that citizens have the some opportunities and experiences. Race, and experiences based on race, are not equal. Thus, the experiences that people of color have with respect to race and racism create an unequal situation. Equity, however, recognizes that the playing field is unequal and attempts to address the inequality. (p. 29)

For far too long within our equal system, we have persistently failed certain groups of students who don’t fit the norm of our educational system. But in a system of equity, all students succeed academically—especially students of Color and those from diverse backgrounds. Fundamentally, schools must change their focus from equality to equity. So, if equity is the paradigm shift educators need to embrace, then what is equity?

REALIZING EQUITY

In 2006 when I first visited Northrich Elementary, a highly diverse school just outside of downtown Dallas, Texas, I expected something special. But what I discovered was the realized ideal of modern education: all students performing at grade level and above regardless of race, socioeconomics, and language. No racial achievement gaps. No economic gaps. No language gaps. Yet many people thought this school couldn’t be successful because the school’s students were over 50 percent Latino, about 25 percent Black, over 75 percent were on free and reduced-price lunch, and about a third were English language learners. Nevertheless, the staff at Northrich had equitable led 100 percent of their students to grade-level proficiency and above in all subjects. For me, this represented the end of a quest to find a school that had proven it could succeed with all students. It was the first 100-percent school I had found, and I have since visited many others. For Northrich Elementary, equity became a reality.

I found myself at Northrich Elementary approximately eight months after my son’s birth, thus setting the standard for what I expected in my son’s education. Astounded by this highly diverse school where 100 percent of students were succeeding at grade level, my understanding of how to achieve equity began to crystallize. Equity cannot be characterized as simply a method, program, or set of standards. To quote Ed Javius of EDEquity, “Equity is not a Strategy! It is a Mind-set!” (2006, par. 1)—an expectation, a framework, a way of being, a recognition that what educators do today for students impacts them for the rest of their lives. An equitable school like Northrich has built enough internal capacity and moral purpose to successfully serve the individualized learning needs of every single student. No student is allowed to fail since all educators have personally and collectively embraced the purpose of their work: to individually support and instruct each student so that all learn what they need, when they need it, and in the way each student learns best. Truly, no child is left behind in an equitable institution like Northrich. But, what does it take personally for an educator to realize equity?

MY PATH TO EQUITY

Admittedly, I am not a classroom teacher. Rather, my career with the School Improvement Network has taken me to almost two thousand classrooms and hundreds of schools in search of the very best practices in education. Throughout these travels, I am constantly amazed at what a dedicated teacher and a focused school can accomplish with the wide range of students that occupy today’s classrooms. Time and again, I have known right upon walking into a school whether or not that educational institution successfully educated all of its students, no matter who they were, what they looked like, or where they came from. I have spent many years detailing the pedagogical practices of these teachers and administrators, but I always wondered how to label the intangible beliefs, attitudes, dedication, and vision that exist within these schools. I now define this as equity.

My personal journey toward an ever-developing understanding of equity goes back to my very upbringing: a privileged but non-wealthy White childhood where my parents helped me understand explicitly what it takes to succeed in our society. Nothing ever required me to understand equity and diversity, and why it matters in the lives of today’s students. According to the constructs I grew up with, I did what I was supposed to do, dressed in appropriate ways, stayed in school for twenty years, received a graduate degree, and began a great career. As a White male in our society, all that was left was marriage, a home, children, and traditional “hard work.” With all of this, according to societal norms, my life would be considered a success, and I likely would not only maintain but also increase the comforts I always knew.

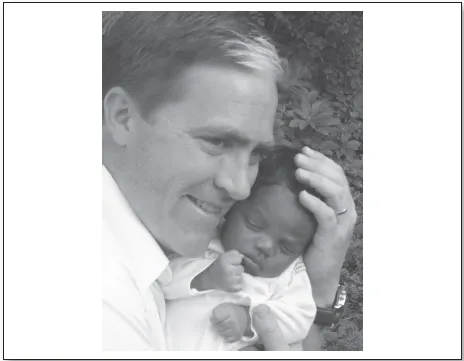

And then at age 31, I held the most beautiful little baby boy in my arms. Finally, I had a son, brought to us through adoption by a birthmother who chose us to raise this child she was inspired should be with us. I instantly placed upon him all the hopes and aspirations I had always carried. From the moment he opened his eyes and looked in my joyful and teary-eyed face, I knew that there was nothing I wouldn’t do to guarantee him all the opportunities and joys he could wish for—and that had always been present in my life.

BLACK AND WHITE

But, my son is Black and I am White. Inherently, I knew I fully loved him no matter his race, but how did this beautiful Black baby in his White father’s arms make things different? How might his race make his dreams different than my own—and should they even be different? Within our home and in our love, he is my son through and through, and nothing else. In society, he is Black on White—a beautiful brown-skinned boy held within peach-toned arms. My son, my boy—all my hopes and dreams embodied in a package that even I, as his father, struggle to fully understand how he is seen within our world.

The troublesome questions from others began immediately: “Is he yours?” “Where did ‘he’ come from?” “Is he a Katrina baby?”

Curtis Linton with his son Dominic, age 1 month

“Have you bonded with him?” Many of the comments we heard from family, friends, and strangers exposed their opinions about his race: “What a beautiful thing you have done for him!” “He is so lucky to have you!” “We’re all the same in God’s eyes!” Wow! My wife and I had heard that interesting things might be said to us when we, as a White couple, adopted a Black baby, but the comments and questions deeply concerned us. We now knew that we were no longer safely normed within the predictable and dominant White society we had always known. The crossroads of race was carrying out right in our very arms.

What did all this mean? “Oh, he is so tall and look at those long hands—he is going to be a basketball player.” Was that meant as a racial stereotype—Black and tall equals pro sports? Or was the phrase “we are so lucky to have a child who will make us so much money [in sports]” (this was actually said) really meant as a compliment? Could what was said just have been meant as a point of conversation because the other person doesn’t quite know what to say when faced with this confluence of race? Or, was the person actually sincere in the comment? Suddenly my wife Melody and I were dealing with race on a personal and immediate level that we had never before experienced, and it rattled us. All we wanted was to love our son and raise him successfully, but society demanded of us that we address his race on a daily basis—not something a White person in our society is ever expected to do.

Dominic came to symbolize for me all the work that I had done up to that point to understand race, racism, institutionalized inequities, and the need for schools to build equity for all students. My own path to equity, however, goes much further back than the birth of my son. It includes my parents, neighborhood, education, coauthoring with Glenn Singleton (2006) the book Courageous Conversations About Race, diverse life experiences, and the many powerful conversations I had with the best educators discussing what it takes for all kids to succeed. To center one’s self in equity is not a checklist, but rather a process that involves the following:

- Understanding one’s own history

- Embracing diversity

- Discovering race

- Norming difference

- Authenticating one’s self in the present

The purpose of engaging in this process of centering one’s self in equity is simple: if someone does not understand deeply one’s own realities, it is very hard to help others—such as students—successfully negotiate their own realities.

UNDERSTANDING MY HISTORY

I grew up in a very homogenous suburb of Salt Lake City, Utah. All around me were mostly White, middle-class, Mormon households— with the exception of two families in my neighborhood: one Latino and one Polynesian. That was nearly the extent of diversity in my upbringing, other than family trips driving across the country and into Mexico where we would see—but not really get to know— people who were different from ourselves. It wasn’t that my family outwardly feared or avoided diversity, we were just very naive to the experience of color and difference and ignorant to the complexities of race in U.S. society.

While growing up, similarity was the norm—the pressure was to fit in, and the rewards followed those who fit in best. All of my schooling was in Advanced Placement (AP) and honors classes, not because I was particularly intelligent, but because I so perfectly fit the norm, teachers intuitively knew how to teach me, and I knew concretely how to succeed in my community and school. The doors of opportunity were open to me and supportive hands were willingly extended. All of this led to the development of a strong belief in my own individuality and ability to succeed. Inherent to my own identity development as a White middle-class male was the confidence that comes with epitomizing the norm: if I could so easily figure out school, wasn’t it likely that I would succeed throughout the rest of my life?

Critical to my own development in understanding equity was my parents’ work nationally in school improvement. Without explicitly understanding that they were working toward social justice, they embarked on a twenty-year journey of changing kids’ lives through improving education. My parents started the Video Journal of Education while I was still in high school. Their company had the express purpose of documenting, on video, the very best teachers and schools in North America from which they created powerful professional development materials wherein educators could learn from other educators. The company was a brainchild of my father, who was both a filmmaker and a schoolteacher. From the first day of teaching, he realized he did not know how to effectively instruct his students. With his experience in film, he envisioned placing a camera in the classrooms of the best teachers in the school and learning from them.

Several years later, he and my mother—a successful elementary school teacher—took out their retirement, bought a professional video camera, and drove across the country filming in the best schools they could find. They contacted the top experts at the time (William Glasser, Michael Fullan, Diane Gossen, William Purkey, Heidi Hayes Jacobs, and many others), filmed their workshops, and visited the schools where these experts’ practices were being implemented. Firmly dedicated to the mission of improving student learning, they created video-based professional development programs based upon the work of actual educators, not just the theories.

Throughout my undergraduate and graduate college studies, I worked for the Video Journal of Education as a cameraperson and program writer. It was great work for a college student—it paid well, had flexible hours, and I traveled the country visiting schools in every state and every demographic. Even though I had no intent to work in education, as my dreams were in filmmaking, these experiences taught me two primary things: (1) there was phenomenal diversity throughout this country—diversity I neither knew nor understood, and (2) dedicated educators can accomplish amazing things with their students when applying the right practices and beliefs.

EMBRACING DIVERSITY

As I began my master’s degree in fine arts in film and television production at the University of Southern California, my wife and I embraced the opportunity that Los Angeles provided us to live in a very diverse community. This was our chance to have what I once described as an “ethnic” experience. Los Angeles is a seething cauldron of difference as defined by race, language, ethnicity, and economics. It was a city wherein we as White people could choose to live among people of Color, experience their cultures, partake in the seeming exoticness of such a neighborhood, and then feel good about ourselves because we were so open-minded and accepting of the people who already lived there.

Finding an apartment in Korea Town, a part of Los Angeles that was 70 percent Latino, 20 percent Korean, and 10 percent everything else, we were now in the minority of people who looked like us. We loved the wide diversity of friendships we developed with numerous races, nationalities, and languages represented in the circle we knew. We embraced urban living and saw...