Mindsets and Moves

Strategies That Help Readers Take Charge [Grades K-8]

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

What if you could have an owner's manual on reading ownership? What if there really were a framework for building students' agency and independence?

There's no "what if?" about it. When it comes to teaching reading, Gravity Goldberg declares there is a structure, one that works with your current curriculum, to help readers take charge. The way forward Gravity says lies in admiring, studying, and really getting to know your students.

Consider Mindsets & Moves your guide. Here, Gravity describes how to let go of our default roles of assigner, monitor, and manager and instead shift to a growth mindset. Easily replicable in any setting, any time, her 4 Ms framework ultimately lightens your load because they allow students to monitor and direct their reading lives.

- Miner: Uncovering Students' Reading Processes (Focus: Assessment)

- Mirror: Giving Feedback That Reinforces a Growth Mindset (Focus: Feedback)

- Model: Showing Readers What We Do (Focus: Demonstration]

- Mentor: Guiding Students to Try New Ways of Reading (Focus: Guided Practice and Coaching)

Get started on the 4Ms tomorrow! Gravity has loaded the book with practical examples, lessons, reading process and strategy lists, and a 35-page photo tour of exemplary reading classrooms with captions that distill best practices. All figures, student work and photographs are provided in vibrant, full color.

We are in the midst of an ownership crisis, and readers of every ability and in every grade are more often compliant than fully engaged. Use Mindsets & Moves as that rare resource that

makes something highly complex suddenly clear and inspiring for you.

GRAVITY GOLDBERG is coauthor of Conferring with Readers: Supporting Each Students' Growth and Independence (Heinemann, 2007) and author of many articles about reading, writing, and professional development. She holds a doctorate in education from Teachers College, Columbia University. She is a former staff developer at Teachers College Reading and Writing Project and an assistant professor at Iona College's graduate education program. She leads a team of literacy consultants in the New York/New Jersey region.

"Mindsets and Moves addresses, in a very engaging way, the most important aspects of classroom literacy instruction. It shows how to think about and interact with children around literacy. Thoroughly grounded in current theories, which are clearly explained and illustrated with stories and examples, the book is absolutely practical with excellent examples of lessons, anchor charts and all of the necessary details." — Peter Johnston, Author of Choice Words and Opening Minds

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

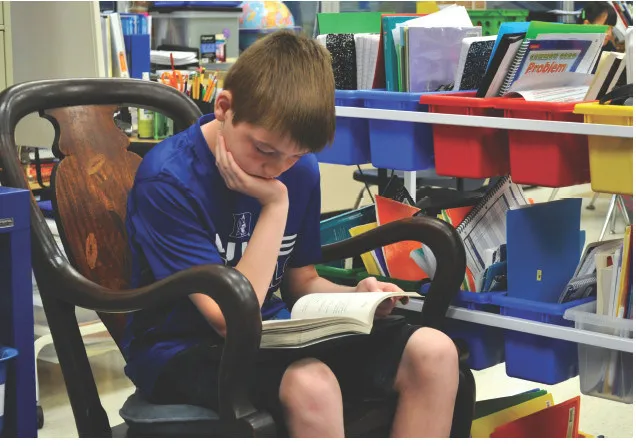

CHAPTER ONE Reading on One’s Own What We Really Mean by Take-Charge Independence

- All students are worthy of study and to be regarded with wonder.

- All students are readers, yet their processes may look different.

- All students can learn to make purposeful choices about their reading.

- All students can develop ownership of their reading lives.

What Does It Really Mean to Read on One’s Own?

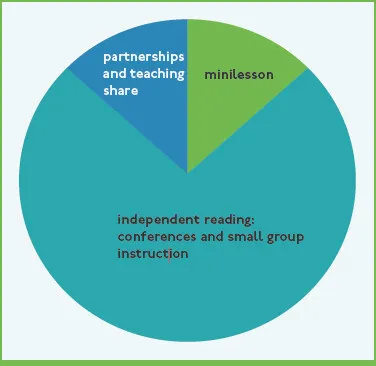

Parts of a Reading Workshop

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Publisher Note

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Publisher Note

- CHAPTER ONE Reading on One’s Own What We Really Mean by Take-Charge Independence

- CHAPTER TWO Shifting Roles Be a Miner, a Mirror, a Model, a Mentor

- CHAPTER THREE Being an Admirer Looking at Readers With Curiosity

- CHAPTER FOUR Creating Space for Ownership A Photo Tour of Reading Classrooms

- CHAPTER FIVE Be a Miner Uncovering Students’ Reading Processes

- CHAPTER SIX Be a Mirror Giving Feedback That Reinforces a Growth Mindset

- CHAPTER SEVEN Be a Model Showing Readers What We Do

- CHAPTER EIGHT Be a Mentor Guiding Students to Try New Ways of Reading

- CHAPTER NINE Teaching Students Strategies for How to Be Admirers

- CHAPTER TEN Embracing Curiosity Entry Points for Getting Started

- Appendix A Student-Focused Reading Checklist

- Appendix B Continuum: How We Might Shift Our Instruction Toward Ownership

- Appendix C Chart of Balanced Literacy Reading Components

- Be a Miner

- Be a Mirror

- Be a Model

- Be a Mentor

- References

- Index

- Publisher Note

- Publisher Note

- Publisher Note