Deliverology in Practice

How Education Leaders Are Improving Student Outcomes

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Deliverology in Practice

How Education Leaders Are Improving Student Outcomes

About this book

Everything you need to implement school change that gets results!

If you've been wondering how to effectively lead and manage results-driven, system-wide implementations, look no further. Internationally recognized education expert Michael Barber explores exactly how to translate policy into practice for long-term, measurable results.

Building on his groundbreaking book, Deliverology 101, Barber provides proven methods and clear steps to achieve successful policy implementation and offer practical solutions for reviving stalled reform efforts. New cases studies and embedded links help you develop a delivery "skillset" for building capacity, effective coalitions, and a coherent, flexible plan for implementation.

Leaders and staff at both national and local levels will learn to:

- Establish a Delivery Unit to set clear, measureable goals and build a reform coalition

- Understand delivery through data analysis and strategic progress monitoring

- Plan for delivery with explicit, day-to-day implementation planning updated with proven methods from years of practice

- Drive delivery with progress monitoring, momentum building, and course corrections

- Create an irreversible delivery culture by identifying and addressing challenges as they occur

Don't leave your education policy implementation to chance. Use this new field guide to get your implementation on the right track today!

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part 1 Develop a Foundation for Delivery

- Define your aspiration

- Review the current state of delivery

- Build the Delivery Unit

- Establish a guiding coalition

Chapter 1A Define Your Aspiration

System Leader Summary

Is This Really Necessary?

Core Principles

- What do we care about?

- What are we going to do about it?

- How do we measure success?

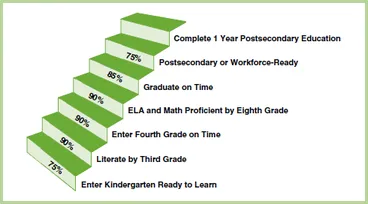

- Are more Kentuckians ready for postsecondary education?

- Is Kentucky postsecondary education affordable for its citizens?

- Do more Kentuckians have certificates and degrees?

- Are college graduates prepared for life and work in Kentucky?

- Are Kentucky’s people, communities, and economy benefiting?

- Senior enough to be respected throughout a system (they are usually members of the leadership team);

- Flexible enough to wear two hats (managing their goal while continuing to manage a division of the office); and

- Willing and able to build the necessary relationships across divisions to break down siloes and exercise influence without authority.

- Identify existing aspirations and goals;

- Prioritize and refine the aspiration; and

- Communicate the aspiration.

Identify Existing Aspirations and Goals

Table of contents

- Cover

- Acknowledgements

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Introduction The American Implementation Problem

- Part 1 Develop a Foundation for Delivery

- Chapter 1A Define Your Aspiration

- Chapter 1B Review the Current State of Delivery

- Chapter 1C Build the Delivery Unit

- Chapter 1D Establish a Guiding Coalition

- Part 2 Understand the Delivery Challenge

- Chapter 2A Evaluate Past and Present Performance

- Chapter 2B Understand Root Causes of Performance

- Part 3 Plan for Delivery

- Chapter 3A Determine Your Reform Strategy

- Chapter 3B Draw the Delivery Chain

- Chapter 3C Set Targets and Establish Trajectories

- Part 4 Drive Delivery

- Chapter 4A Establish Routines to Drive and Monitor Performance

- Chapter 4B Solve Problems Early and Rigorously

- Chapter 4C Sustain and Continually Build Momentum

- Part 5 Create an Irreversible Delivery Culture

- Chapter 5A Build System Capacity All the Time

- Chapter 5B Communicate the Delivery Message

- Chapter 5C Unleash the “Alchemy of Relationships”

- Conclusion Over to You

- Index

- Publisher Note