![]()

1

Working With

Young Children

Children are our future. Being in a position to work with children and guide them through the maze of learning experiences is both a special privilege and a challenge. Success in meeting this challenge is dependent upon our love for children, our understanding of them, and the knowledge we have regarding the planning and implementation of activities that encourage their growth and development.

Information about the brain and learning has emerged very rapidly since the decade of the 1990s and continues into the present. As a result, we now have an expanded knowledge base from which we can provide a stronger support system for the development and learning of all children. Throughout this book you will find concrete ways to put into practice the necessary elements to enhance the growth and development of children by meeting their learning needs in all areas of development. To lay the foundation for putting strategies for working with young children into operation, the first part of this chapter presents a summary of some of the major findings from brain research. The second part of this chapter is devoted to child development concepts that have stood the test of time and resonate with the findings from brain research.

MAJOR FINDINGS FROM BRAIN RESEARCH

Most theorists now believe that both nature and nurture play a significant role in a child’s development and ultimately who that child becomes. There is an acknowledgment that everyone comes into the world with a genetic inheritance (nature). However, it is the environment (nurture) that provides the stimuli for an individual’s growth and development relative to intelligence, talents, and social abilities. The nature and nurture concept is significant information for all parents and adults who are responsible for a child’s well-being and learning. The nature with which children come into the world plus the type and amount of environmental stimulation is a dynamic interaction represented by the following equation: Bf = C + E. Behavior (learning, social, etc.) is a function of the child and the environment.

Behavior (physical, mental, emotional, social) = the Child + the Environment

This dynamic interaction makes it imperative that we always consider both factors when providing learning experiences for children and in planning strategies to change their behavior. The power and influence of environmental stimulation and experiences gives encouragement to adults for helping children reach their potential. It is critical that parents of young children, child care providers, and educators understand what this means and apply it to all environments where children live, play, and learn. Creating these environments is a wonderful opportunity to help children develop their potential. At the same time, it is a major responsibility to provide the environments that will support each child’s growth and development. To be most effective, the timing of different types and amounts of stimuli should coincide with the child’s readiness to receive it.

Children come into the world with a full set of (about 100 billion) brain cells (neurons). Stimuli from the environment are mandatory for these neurons to grow, develop, and form pathways of communication. These pathways are necessary to provide the means for language development, visual abilities, motor functions, and social and emotional growth to take place. The foundations for the development of these mind/body functions begin during the prenatal period. From birth to the first five or six years of a child’s life is a critical time for the brain’s neural pathways to be hardwired. Future learning and behavior are dependent upon the communications between the neurons in the brain and the cells throughout the body that are established during these early years. Young children need experiences and nurturance from adults to accomplish this important task. The richer the environment, the greater the number of interconnections are made. Consequently, learning can take place faster and with greater meaning.

In being and working with children, it is necessary to approach all we do from a mind/body/heart approach. Neuroscientists and other researchers devoted to studying the physiology of the mind/body/heart have established that these three components are interconnected and work in concert with each other. What we eat affects how we think and feel. What we think and feel affects our body’s functions. In other words, cognition, emotion, and physiology are all intertwined. What we do for or to our body directly affects our ability to reason and to maintain a state of emotional balance. What happens to children (and adults) emotionally either enhances or compromises thinking ability and body functions. The body, brain, and emotions contribute to each other in complex and interdependent ways. Knowing this dynamic interplay can help adults to become more aware of ways to provide conditions and experiences that contribute to a balanced state of being rather than the less productive state of imbalance. For more information on this topic, refer to the books, Creating Balance in Children’s Lives (Moore, 2005) and Creating Balance in Children (Moore & Henrikson, 2005).

Until recently, emotions were viewed from a psychological perspective consisting of both mental and feeling processes. As scientists became more adept at measuring the effect of emotions on body functions and reasoning abilities, emotions as a study moved into the circle of topics worthy of scientific enquiry. For example, scientists conducting research at the Institute of HeartMath in Boulder Creek, California, have measured the power of emotions by tuning in to heart frequencies and variability rates. They have found that the heart and the brain are constantly communicating with each other via the pathways of the nervous system to connect our thoughts, emotions, and body systems. Emotions, the physiological response of the body to external stimuli, are activated when one or more of our five senses take in information from the environment. This information is then evaluated by the brain’s feeling and thinking systems to determine which response is needed. The response can vary from joy and excitement to anger and despair, which response in turn affects our cognitive and body functions either in a positive, neutral, or negative way.

In working with children, we have often underestimated the power of emotions in their lives. Emotions play a critical role in their growth and development and how they view the world around them. Positive emotional input from caring adults sets the stage to support a child’s physical, mental, and social development and overall well-being. Negative input or lack of emotional support not only compromises a child’s learning but puts that child at risk for viewing self, others, and the environment from a hostile or defensive perspective.

Through scientific research, nutrition has been found to have a direct link to learning and behavior. A balanced diet containing all the necessary nutrients, such as complex carbohydrates, protein, “healthy fats,” vitamins, and minerals, is needed for the brain and body to support learning and appropriate behavior. Diets that consist of “fast foods,” other processed foods, and sugar have been linked to poor attention, learning difficulties in academic subjects, and behaviors associated with hyperactivity, aggression, and depression. There has been an increase in national concern about the health of our nation’s children as obesity rates and the onset of type 2 diabetes have increased among today’s children. It is now a well-known fact that obesity among today’s children has reached an epidemic level. The long-term consequences of obesity when the children of today become adults is yet to be determined. However, at this point we do know that type 2 diabetes can be linked to obesity, and with both obesity and diabetes come a compromised health system. Behavioral problems have also been on the increase, as observed by the increased number of children of school age on some type of medication, and with medication use extending downward to younger children. One of the more promising alternatives to medication has been to treat children by natural means such as through diet (Stordy & Nicholl, 2000). Since nutrition is now accepted as a science, more researchers are committing their time and resources to carrying this endeavor further in order to expand our knowledge of the relationship between nutrition and learning and nutrition and behavior.

Mind/body/heart research has provided us with a substantial body of updated information to help us understand and work with children more effectively. This gives practitioners a scientific basis for evaluating current child development practices to determine which practices to keep and which to change or discard. The ideas and strategies expressed in the remaining pages of this chapter and throughout the book are consistent with the mind/body/heart research.

“WHOLE CHILD” PERSPECTIVE

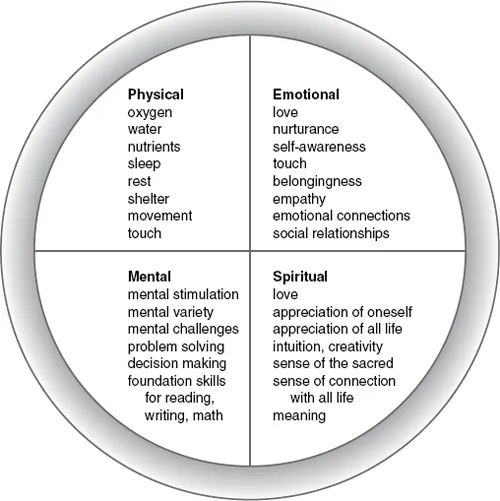

Children need to be viewed from a “whole child” perspective in order to encourage and ensure a balance in their growth and development. It is the responsibility of adults to be aware of and to address the physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual needs of each child. An example of what each category encompasses is shown in Figure 1.1.

If one area is overemphasized relative to other areas, children will not obtain the balance they need to develop as “whole people.” Balance is critical for children to attain their full potential in all realms of life.

Figure 1.1 Categories of Development

Addressing the needs of the whole child in a learning environment gives children the opportunity to optimize talents as they surface and to address their individual needs, which may be expressed as limitations. This becomes especially significant for children who experience difficulty in the learning process, as they tend to translate their areas of difficulty to all areas of their lives.

How children feel about themselves is based both upon the love and understanding they receive and upon their performance. Children with learning difficulties need to be encouraged and supported in the processes of discovering their talents and learning to use them. This allows them to develop positive feelings about themselves as people. The possibility of young children imposing the stigma of their learning difficulties universally on all areas of their lives without recognizing their talents in other areas is something that educators and parents need to recognize and prevent in order to avoid the establishment of permanently formed negative patterning.

DEVELOPMENTALLY APPROPRIATE PRACTICE

Everything we plan and do with children needs to be based on the concept referred to as developmentally appropriate practice. This concept is based on two principles. The first principle conveys the fact that all practices in working with children need to reflect realistic expectations for children typical of their age group. The second principle refers to the fact that practices in working with children should also be individually appropriate. Practices that are both age appropriate and individually appropriate provide the greatest opportunity for children to develop and learn at a pace that will maximize their progress. One application of these principles can be observed in curricula such as those based on the concept of differential instruction.

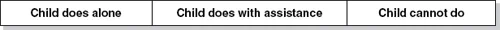

Development and learning are interdependent. This relationship can be implemented for each child by planning and delivering instruction and materials that fall within a child’s zone of proximal development, a concept developed by L. S. Vygotsky, a Russian psychologist. According to Vygotsky, a child’s level of learning and progress is determined by knowing where a child is when placed on a continuum of mastery from “can do independently” to “cannot do.” This links learning to development. Expanding on Piaget’s work, Vygotsky applied the concept of how social interactions and collaboration supported learners in the learning process. The zone of proximal development continuum appears as shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Zone of Proximal Development

A child’s placement on this continuum for a specific area of development is based on observation of the child’s spontaneous behaviors and the child’s assisted behaviors. Informal and formal testing can supplement the observations made by the adults working with a specific child. The zone of proximal development for a particular child lies between what the child can do unassisted and what the child can do if prompted by a peer, an adult, or some other stimulus. Possible supports include interaction with the teacher, another child, or equipment and materials. All children can do more with support than they can manage alone, but the direction of growth, development, and learning is toward independence.

Another important aspect of linking learning to development is to be aware not only of where a child is in his overall development, but also where the child is in each area of development. This includes assessing where a child’s language, motor, visual-motor integration, cognitive, social, and emotional abilities and adaptive behaviors lie on the developmental continuum.

It is important to remember that a profile depicting an uneven development of abilities is not uncommon for young children. This is certainly true for children with special needs where, in some instances, a child may be within an average range of development in one or more areas, but be significantly delayed in others.

An example of a profile of even and uneven development appears in Figure 1.3. What constitutes a severe delay for placement into special education needs to be determined according to your school district’s criteria. In most cases, age-level scores need to be translated into standard scores for placement purposes. As a general guideline, the Gesell Institute of Human Development uses ± six months of a child’s chronological age as representing development within a normal range of expectation. The Gesell Institute is an excellent source of information for understanding and measuring children’s developmental ages relative to areas of development and age expectations. Their Web site can be found in Appendix B.

Figure 1...