![]()

1

Learner Independence

The greatest sign of success for a teacher … is to be able to say, “The children are now working as if I did not exist.”

—Maria Montessori (2007, online)

Like every teacher, we want what is best for our students: while academic standards are held high, we strive for all learners to feel capable, valued, and powerful. We work diligently to interact with students in a way that will bring them success in both the classroom and the real world where our teaching ultimately is intended to impact students’ lives. Throughout our years of teaching, we have found that learner independence consistently contributes to student success, but facilitating learning that fosters habits of independence can be a challenge.

Although we could craft a lesson, manage a classroom, and prepare for student learning, questions about our teaching practice remained. Can learner independence be taught? When is independence an appropriate expectation? And perhaps most importantly, what is learner independence? In sifting through our experiences, we first decided what learner independence is not: learner independence is not freedom without accountability, nor is it the systematic knowledge and completion of routines and procedures. Independence is not quietly staying on task and keeping busy or finishing work without teacher support. Learner independence has more to do with the thinking behind the decisions we make and the actions we take. The behaviors that belong to a truly successful learner are more complex than just following protocol and being self-sufficient.

In order to further understand independence in the classroom, this chapter is devoted to defining learner independence, examining how it impacts student self-esteem, and analyzing the thinking habits of truly independent learners. Just as we took time to sift and sort through what we understood about learner independence, it is important that you analyze and evaluate your prior experience with respect to this topic. Reflect on the following questions and jot down some of your current understandings to support you as you read the rest of the chapter.

• What is learner independence?

• Why is the concept of independence important and to whom is it important?

• What kinds of teacher behaviors encourage students to be independent learners?

• What do I do now to encourage independent learning?

DEFINING LEARNER INDEPENDENCE

It would be an error to assume that our definition of independence matches that of our readers; therefore it is essential to clarify this term from the beginning. When we researched independence in the dictionary (Merriam-Webster Online, 2007), we found over twenty definitions. As we analyzed the myriad of descriptors that followed ‘independent,’ we began to see just how complex deciding upon a common definition could be. While no one definition truly supported our thinking of independent learners, we concluded that to agree upon one definition was the only way to have common grounds for our written and verbal conversations. Our working definition is as follows:

Independent learners are internally motivated to be reflective, resourceful, and effective as they strive to accomplish worthwhile endeavors when working in isolation or with others—even when challenges arise, they persevere.

As we worked to create this definition, we aimed to keep it short and concise, making sure that this definition encapsulated all that we believe and understand about independent learners. We had many discussions about what was meant by “internally motivated,” “reflective,” “resourceful,” “effective,” and “worthwhile endeavors.” These are ideas that we will clarify throughout our book.

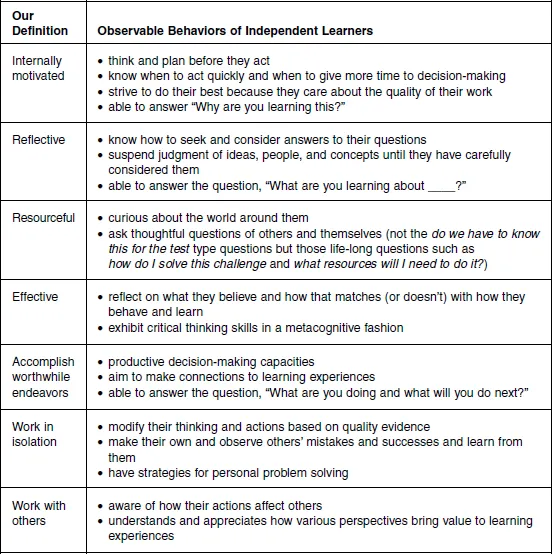

To expand on our definition and its relevance to the classroom, let us take some time to explain some of our wording. For example, notice how we wrote that independent learners are able to accomplish worthwhile endeavors whether they work in isolation or with others. Although others do not control them, independent learners are influenced by others’ thoughts, beliefs, and actions. This influence occurs once the learner has the opportunity to sift and sort information, and as a result, he formulates his own ideas, culminating in a set of core understandings and beliefs. Through the reflective process, learners ask questions of themselves and of others, and make decisions based upon a clear set of standards. Learners who are independent proceed with confidence as a direct result of seeing the consequences of their decision-making process. Independent learners look similar to students who exhibit high levels of responsibility. In order to identify independent learners, you must further analyze the students’ work, words, and actions for attributes of learner independence. Students who are independent do well with intrapersonal tasks as well as with interpersonal experiences. It may be helpful to describe independent learners in further detail by breaking down specific behaviors and by explicitly identifying them as actions of independence. As you read this list in Figure 1.1, you may want to consider how these descriptions relate to students you know.

Figure 1.1 Elements of Learner Independence

There is no magic age at which we suddenly become independent learners; we’ve met toddlers who exhibit many of these characteristics and adults who show limited use of most of these behaviors. Ultimately, our goal is for students of all ages to develop characteristics of independence. As you read this book, we will clarify our definition further and help you to expand upon the definition for yourself. It is our hope that you take our working definition and use it to create your own understanding of independent learning.

To aid you in creating your own definition, think about when you learned to drive. Most teenagers use their independent learning skills as they earn their driver’s license. Did you make mistakes and learn from them? Did you watch others make mistakes and learn from those errors? When you made a lane change and almost hit a car driving in your blind spot, was your thinking modified? Did you check your blind spot when doing future lane changes? Are you careful not to drive in other people’s blind spots? Were you curious about learning how to parallel park? Were you thinking and planning before you acted? Most likely you were using critical thinking skills, productive decision-making capabilities, and you had an incredible sense of internal motivation. It is very unlikely to hear someone in a drivers’ education class ask, “Why do we have to learn this?”

Whereas driver’s education is unquestionably motivating, we believe it doesn’t require a topic like this to encourage independent learning skills in students. We can set up any learning environment to help students develop the critical life skill of being an independent learner. Most people are motivated to be independent learners as they learn to drive and a huge part of that is because they have an authentic purpose for learning the skills associated with driving. We believe that teachers can set up their classrooms so that students have genuine purposes for their learning. Research has shown that authentic learning experiences, rather than tasks that are void of meaning for learners, have a positive impact on learning. Duke, Purcell-Gates, Hall, and Tower (2006) monitored the authenticity of literacy activities in a variety of classrooms. They found that those teachers who included a greater number of authentic literacy activities more of the time had students who showed higher growth in both comprehension and writing. We can only conclude that incorporating genuine literacy into the classroom increases learner engagement, thus impacting student learning.

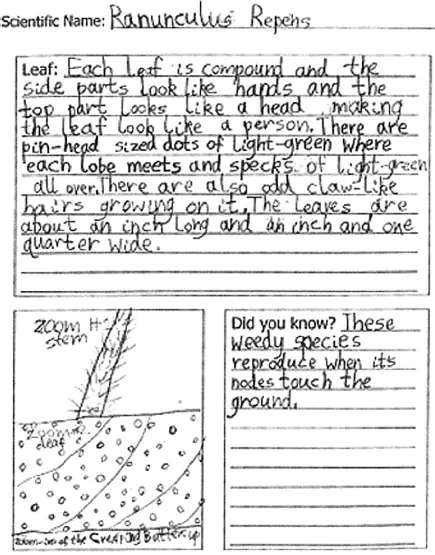

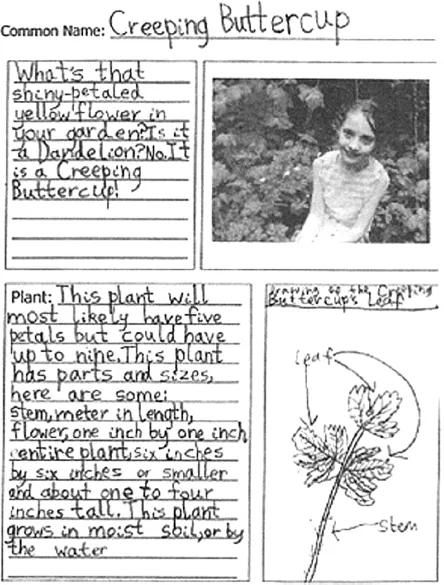

A recent article found in the National Science Teachers Association’s journal, Science and Children, provides another example of how an authentic learning experience impacts student independence. The article (Coskie, Hornof, and Trudel, 2007) summarizes a five-week study that taught students how to write a field guide (Figure 1.2) that identified the plants in a small wooded area on their school property. By creating this authentic genre of scientific writing, students came to understand and care for the natural world in their immediate environment. They also developed important science, reading, and writing skills through purposeful work. Once their field guides were published, the students’ families were invited to a special afterschool event where students took their guests on a scavenger hunt. The authentic learning opportunity culminated when students had the opportunity to watch their guests use their class-created field guide to find each plant listed in the scavenger hunt list.

Our goal is to develop learners, and in turn, citizens who rely on an intrinsic desire to keep learning. Children are naturally curious, and we believe that tapping into this internal drive to inquire and discover can encourage habits of independence in learners. School can be a place to foster the growth of the independent learner at any grade, age, or stage of development. Success comes to those teachers who figure out how to further develop independence in themselves and in their students, while still meeting or exceeding academic standards.

Figure 1.2 Sample Field Guide Page

SOURCE: From Coskie, Hornoff, and Trudal (2007). Reprinted with permission from Science & Children, a publication for elementary level science educators published by the National Science Teachers Association (www.nsta.org).

LEARNER INDEPENDENCE ENCOURAGES SELF-ESTEEM

As adults, we have a vast repertoire of experiences, some of which resulted in success, whereas others ended in failure. Reflect on your own life and think about a specific skill that resulted in success and another that resulted in failure. Which are you more likely to continue, the activity that was “doable” or the one that was seemingly impossible to accomplish? Although there are exceptions when people have chosen to prevail over failure, as a rule people choose to continue with a specific activity when it positively contributes to their self-esteem. How many adults have you met who openly admit that they hate math because they struggled in school? What about people who choose not to read for pleasure because it was a chore growing up? The same concept can be transferred to young learners: how students feel about their own capabilities influences their ability and internal drive to learn. This does not mean that learning should be easy for students and all attempts successful. As teachers, this knowledge should drive us to set up learning experiences where students take on a challenge because they are equipped to do so. Kostelnik, Whiren, Soderman, Stein, and Gregory (2002) have identified three dimensions to self-esteem: competence, worth, and control.

• Competence is the belief that you can accomplish tasks and achieve goals.

• Worth can be viewed as the extent to which you like and value yourself.

• Control is the degree to which people feel they can influence the events around them.

Examining each of these qualities can help a teacher concentrate on specific ways for developing habits of learner independence while impacting self-esteem. We have chosen specific examples, not to tell you how to promote learner self-esteem but to demonstrate why each of these components is such a powerful influence in contributing to student independence.

Competence is the belief that you can accomplish tasks and achieve goals. Select from your experiences a time in which you felt encouraged to continue on a specific task, not because of your automatic mastery, bu...