![]()

1

Reflecting on Your Mentoring Practice

The Story of My Mother’s Gravy

Mentors and apprentices are partners in an ancient human dance, and one of teaching’s greatest rewards is the daily chance it gives us to get back on the dance floor. It is the dance of the spiraling generations in which the old empower the young with their experience and the young empower the old with new life, reweaving the fabric of the human community as they touch and turn.

—Palmer (1998, p. 25)

Congratulations! Whether you are supporting a first-year teacher in your district, have accepted the responsibility to partner with a university to promote the growth and development of a student teacher, or just have a general passion for advancing the professional growth of teaching colleagues, you are a participant in the ancient human dance described so eloquently by Parker Palmer—mentoring. Congratulations are in order, as the act of mentoring generates tremendous potential for teachers to be renewed professionally. The fatigue and burnout many teachers feel after numerous years in the profession are replaced with a renewed energy for their chosen field. Mentoring is perhaps the single most important act a veteran teacher can engage in to contribute to the future of the teaching profession.

WHY IS MENTORING SO IMPORTANT?

Let’s look closely at some of the logistical variables that heighten the importance of mentoring. First, as a result of demographic trends related to increased student enrollments, teacher retirements, class size reduction, and teacher attrition, an increasing demand exists for public school teachers across our nation. An anticipated two million new teachers will enter the profession within the next decade (U.S. Department of Education, 1999). Florida alone needs 30,000 teachers a year and the colleges of education within Florida are only able to provide about 5,000, leaving a need for 25,000 new teachers. Like many states, Florida is developing alternative pathways to teaching, and as a result, many novices are arriving in their first classroom with limited pedagogical preparation.

Recruiting new teachers to fill these positions is critical, but even more critical is keeping new teacher recruits in the classroom. Statistics on teacher retention are grim—researchers have consistently found that younger teachers have high rates of departure (Ingersoll, 2001). In fact, several organizations, such as the National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, report, “with the exception of a few disciplines in specific fields, the nation graduates more than enough new teachers to meet its need each year. But after just three years, it is estimated that almost a third of new entrants to teaching have left the field, and after five years almost half are gone (National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, 2003, p. 19). In more challenging contexts, both rural areas and inner cities, these rates are often dramatically higher. Effective mentoring is an essential answer to the daunting attrition-rate problem (Feiman-Nemser, 1996). We need strong mentor teachers, and we need them fast!

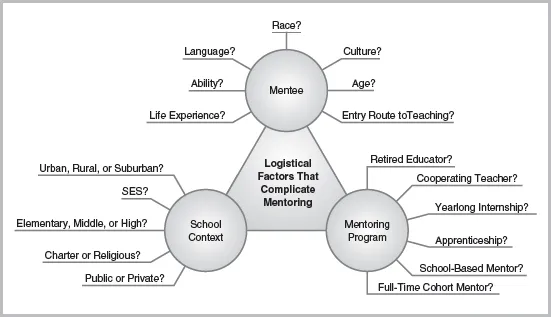

Because the need for new teachers is so great, alternative entries to teaching accompanied by mentoring programs have sprouted up across the nation to augment the more traditional university student teacher or full-year internship teacher preparation model. In our work with mentoring, we have witnessed several different mentoring approaches that support traditionally and alternatively prepared teachers, including the following:

• Retired Educators—Mentors are retired teachers and administrators hired by a district to serve as part-time mentors of new inductees. Typically, these retired educators are less familiar with the school context, curriculum, and students within the classroom, but have numerous years of teaching experience to draw upon as they help others learn to teach.

• Cooperating Teachers—Mentors are classroom teachers who host a university student in their classroom for a single-semester student-teaching experience. Typically, these mentors view their role as providing a context for the novice to learn to teach and consider the onus of the responsibility for the new teacher’s success as that of the university teacher education program.

• Yearlong Internship—Mentors are classroom teachers who coteach within their classroom with a yearlong intern from a university. These yearlong internships often unfold within professional development schools, where the mentor conceives of himself or herself as a school-based teacher educator.

• Apprenticeship Model—Mentors are classroom teachers who coteach with an alternatively certified teaching candidate. The teaching candidate, or apprentice, is paid as a paraprofessional during the apprenticeship year and assumes his or her own classroom the following school year.

• School-Based Mentor—Mentors are typically peers who have their own classrooms within the same school and assume the extra responsibility of mentoring a novice. This person may or may not have experience in the same grade level or subject matter as the novice and typically receives a small stipend.

• Full-Time Cohort Mentor—Mentors are responsible for supporting a cohort of new teachers placed within a single school. This model typically emerges in schools with high teacher turnover and large numbers of alternatively prepared, uncertified teachers. This mentor typically becomes a full-time member of the school faculty and becomes intimately familiar with the students, curriculum, and resources in the school and community.

The model within which you find yourself mentoring has implications for the types of support your mentee will need. For example, you may be mentoring preservice teachers in an undergraduate-or graduate-level teacher education program with relatively little classroom experience. You may be mentoring new teachers in your school who are engaged in the induction phase of their career and who are graduates of traditional teacher education programs and have completed a student teaching or internship experience. You may be mentoring new inductees at your school who increasingly arrive through alternative routes to teaching as they transition from a wide range of other careers, including the military, accounting, social work, and others.

In addition to these varied entry routes to teaching, novice teachers vary tremendously in age, life experiences, culture, race, language, and ability. They each bring to their teaching career teaching knowledge gained through their own experiences in K–12 education. Some of their experiences may be quite consistent with research-based teaching practice; however, the majority of these new teachers may possess beliefs that run counter to what is currently known about powerful instructional practice.

This immense variability in who is being mentored heightens the need for strong mentor teachers who possess a sensitivity to differentiating mentoring practice based on their mentee’s background, life experiences, and needs. Mentors need to individualize for every new teacher, and each individual mentor teacher will need to carefully consider how he or she will facilitate the novice teacher’s development. Figure 1.1 presents the logistical factors that contribute to the need to individualize for every mentee, illustrating the complexity of mentoring. As a result of this need for differentiation, tremendous responsibility is placed on your shoulders to support the success and survival of both the novice teacher you are mentoring and the children who learn within the novice’s classroom. Remember, the survival of the novice teacher refers to whether they are able to navigate the complexity of the work life of a teacher within a bureaucratic system. The success of the novice teacher connects to the novice’s ability to help children learn. Mentoring requires your attention to both survival and success.

In addition to the distinction made between novice teacher success and survival, who you are as a mentor teacher and who your mentee becomes as a classroom teacher is also dependent on your school context. Are you mentoring in a rural, urban, or suburban community? What is the socioeconomic status of the students in the school you serve? Are you teaching in an elementary, middle, or high school, and is that school public, private, religious, or charter? The logistical variables alone that surround mentoring serve to heighten the importance of quality mentoring! Regardless of who you are mentoring, or in what context you are mentoring them, this book is designed to help you visualize your role as mentor, differentiate for each mentee you work with, and enhance the mentoring skills you already possess and enact each day in your work with novice teachers.

HOW DO YOU ENHANCE YOUR MENTORING SKILLS?

Mentoring requires planned, intentional reflection on the ways years of experience as a thoughtful, reflective, reform-minded teacher can be captured and translated effectively to the next generation of teachers. We define reform-minded as a progressive stance toward teaching that acknowledges the importance of research-based practices, problematizing teaching and learning, and embracing change with the aim of educating all children. The goal of mentoring must be to cultivate these reform-minded practices in the novices who are entering the profession.

In the past decade, there has been a heightened interest in mentoring. Similarly, teacher education reformers “regard the mentornovice relationship in the context of teaching as one of the most important strategies to support novices’ learning to teach and, thus, to improve the quality of teaching” (Wang, 2001, p. 52). The importance and the heightened interest in mentoring as well as the increasing and pressing need for quality mentors has bred a number of manuals, guidebooks, and workshops on mentoring that identify the basic technical skills necessary for effective mentoring. Texts such as Hal Portner’s Mentoring New Teachers (2003), and Hicks, Glasgow, and McNary’s What Successful Mentors Do (2005) are excellent resources that help mentors develop the foundation for working skillfully with novice teachers. However, in addition to understanding the technical skills that provide the foundation for the act of mentoring, it is also important to reflect on the ways these skills play out with different novices and in different contexts.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO BE REFLECTIVE ABOUT ONE’S MENTORING?

On the surface, this may appear to be a silly question. After all, it would seem that with numerous years of teaching experience under your belt, mentoring would be a natural process that would just happen as a result of sharing the same classroom and children with a student teacher, or in serving as a buddy for a novice teacher, answering questions and sharing district and school procedures to help him or her through his or her first few years of teaching. Yet, research tells us that outstanding teaching does not readily and intuitively translate to outstanding mentoring. For example, in an extensive research study comparing mentor teachers in the United States, United Kingdom, and China, Wang (2001) found that

Relevant teaching experience, though important, is not a sufficient condition for a teacher to be a professional mentor. Mentors who are practicing or moving toward practicing the reform-minded teaching may not develop the necessary conceptions and practices of mentoring that offer all the crucial opportunities for novices to learn to teach in a similar way. Thus, when selecting mentor teachers, not only is it important to consider the relevant teaching experiences of mentors but it is also important to identify how mentors conceptualize mentoring and their relevant experience in conducting the kind of mentoring practices expected. (pp. 71–72)

Identifying how you conceptualize mentoring, therefore, is a critical process that can only happen as a result of reflecting deeply on mentoring. Teaching novices to teach can be extremely rewarding, but extremely complex as well. Consider the summary Wang (2001) provides of the needs of novice teachers:

Research suggests that to learn to teach for understanding, novice teachers need opportunities to form a strong commitment toward reform-minded teaching (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999) and to develop a deeper understanding of subject matter (Ball & McDiarmid, 1989). They need opportunities to learn how to represent what they teach effectively in classrooms (Shulman, 1987) and how to connect what they teach to students with different backgrounds (Kennedy, 1991). They also need opportunities to learn how to conduct the kind of reflection that supports their continuous learning to teach (Schön, 1987, p. 69)

Because the needs of the novice are many, and each novice is different, there is no single way to mentor that will work with every novice in every context in the same way. Mentors need to reflect on their skills and make decisions about which basic mentoring skills must be invoked with each novice in each context at different times and for different purposes throughout the mentoring process. Becoming reflective about your mentoring and developing your own unique mentoring identity through the reflective process deepens your ability to influence the novice teacher. Becoming reflective about your mentoring recognizes the unique challenges individuals learning to teach face, and raises your voice in discussions of reform-minded teaching. Through becoming reflective about your mentoring, you ...