![]()

SECTION II

Taking a Page From the Experts

![]()

6

Thinking Across Disciplines

In 2000, Charles Best was a 25-year-old social studies teacher at a public alternative school in the Bronx. Like many of his colleagues, he was frustrated by the lack of funds to buy basic classroom supplies. Materials for special projects? Forget about it. But Best had a hunch. If ordinary citizens knew that teachers needed additional books or art supplies, wouldn’t they be willing to pitch in? To test his idea for citizen philanthropy, he built a website on which teachers could post modest requests for materials. That was the birth of Donors Choose. By 2012, the award-winning nonprofit had raised more than $100 million for schools across the United States.

The basic idea of Donors Choose remains elegantly simple, but it takes a well-oiled team to make this social enterprise so effective. Behind the scenes, there are Web programmers and social media experts who use various tools and platforms to connect donors and teachers. Data analysts crunch the numbers to show impact, while accountants track the dollars so that donors have confidence about where their money’s going. Marketing experts turn celebrity endorsements (such as repeat shout-outs from comedian Stephen Colbert) into opportunities to expand this successful brand.

Look closely at almost any real-world activity—developing a new consumer product, running a political campaign, investigating a crime, managing a small business—and you’ll find an interdisciplinary team contributing discrete sets of skills and knowledge to the effort. In today’s complex world, this is how important work gets accomplished.

As we’ve discussed in previous chapters, project-based learning prepares students for the world that awaits them by giving them opportunities to work with peers on authentic problems. Good solutions often result from people with different kinds of expertise contributing their best thinking—and building on each other’s ideas. Learning to collaborate with team members is one important outcome of projects. Just as important is the chance to walk in the shoes of expert problem solvers.

This chapter sets the stage for the second half of the book, in which we will explore project-based learning in four core academic disciplines. It might be tempting to think of these fields—language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies—as separate areas of a library, each containing its own collection of content that students need to master. But that would be short sighted. Along with important content, each discipline also offers a distinct set of lenses for viewing the world, investigating questions, and evaluating evidence. As students become more deeply steeped in the disciplines, they learn both rich content and expert ways of thinking.

When students are confronted with real-world problems, they may need more than one set of disciplinary lenses to “see” a complex issue or design a solution. Constructing an answer may require them to integrate ideas or approaches from diverse perspectives.

Before we dive deeply into discussing inquiry strategies for projects in language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies, let’s take time to consider the nature of interdisciplinary thinking and the role it plays in expert problem solving.

PREPARING TO TACKLE COMPLEX PROBLEMS

Most intellectual life outside of school makes connections across disciplines. Indeed, it’s hard to think of a career field or profession that operates in isolation. Filmmakers need financial backers. Doctors must stay current with pharmaceutical research. Anthropologists help technologists understand how people interact with computers. Professional athletes often have teams of trainers, nutritionists, and psychologists to help them stay at the top of their games. Even solitary artists and writers must eventually collaborate with gallery owners, publicists, and publishers if they want to get their creative work to an audience.

People who are experts in their fields have developed a familiarity and fluency with a particular set of tools, methodologies, and types of evidence and argument used in solving problems, accomplishing tasks, and sharing results. They’re part of a culture that has its own history, accomplishments, vocabulary, and perhaps special notations. The most skilled are able to work across disciplines, connecting and integrating what they know about in depth with understanding that comes from other fields. A patent lawyer, for instance, has to be able to “speak” both law and engineering. Someone who coordinates public health campaigns may need to draw on expertise in medicine, behavioral psychology, marketing, and social media.

It’s primarily in school that we wall off the disciplines into content-specific silos and shift students’ attention from one subject to the next with the ring of a bell. John Dewey (Dewey, 2011, p. 62) cautioned against this practice nearly a century ago when he observed, “We do not have a series of stratified earths, one of which is mathematical, another physical, another historical, and so on … All studies grow out of relations in the one great common world.” Learning driven by the traditional bell schedule is distinctly unlike real life, something that critics continue to point out. “We simply do not function in a world where problems are discipline specific in regimented time blocks,” noted Heidi Hayes Jacobs in her 1989 publication Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Design and Implementation (Jacobs, 1989).

The complexity of today’s challenges and the connectedness that technology affords are making interdisciplinary thinking increasingly important. Veronica Boix Mansilla, principal investigator of the Interdisciplinary Studies Project at Harvard’s Project Zero, describes interdisciplinarity as the hallmark of contemporary knowledge production and professional life (Boix Mansilla, 2006; Boix Mansilla & Dawes Duraising, 2007). Cross-cutting issues facing today’s youth range from the ethics of stem cell research to the human role in climate change to the politics of financial reforms. Preparing young people to engage in the major issues of our times requires that we nurture their ability to produce quality interdisciplinary work (Boix Mansilla & Dawes Duraising, 2007).

PROJECTS ALLOW FOR CONNECTIONS

When projects mirror real life, they take learning out of the content silos and challenge students to make connections across disciplines. But this doesn’t mean discounting or discarding subject-area content or ways of thinking that come with the disciplines. Nor does it mean tossing in a dash of math or a smidge of science to make a writing assignment interdisciplinary. Rather, students demonstrate true interdisciplinary understanding when they integrate knowledge, methods, and languages from two or more disciplines to solve problems, create products, produce explanations, or ask novel questions in ways that would not be feasible through a single disciplinary lens (Boix Mansilla & Jackson, 2011).

Informed by both research and classroom practice, Boix Mansilla and colleagues at Project Zero have identified four key features of quality interdisciplinary understanding (Boix Mansilla & Jackson, 2011, p. 13):

Interdisciplinary understanding is purposeful: Students examine a topic in order to explain it or tell a story about it in ways that would not be possible through a single discipline.

Understanding is grounded in disciplines: It employs concepts, big ideas, methods, and languages from two or more disciplines in accurate and flexible ways.

Interdisciplinary understanding is integrative: Disciplinary perspectives are integrated to deepen or complement understanding.

Interdisciplinary understanding is thoughtful: Students reflect about the nature of interdisciplinary work and the limits of their own understanding.

These qualities are worth considering at the project design stage, when teachers are determining the key learning goals they aim to achieve through a project. Is a project idea grounded in a specific content area, or does it allow for meaningful connections across disciplines?

Collaborating with colleagues from other content areas can help teachers recognize natural connections in their content standards. In Meeting Standards Through Integrated Curriculum, authors Susan Drake and Rebecca Burns suggest, “Teachers can chunk the standards together into meaningful clusters both within and across disciplines. Once teachers understand how standards are connected, their perception of interdisciplinary curriculum shifts dramatically.” Indeed, they emphasize that “some teachers see it as the only way to teach and to cover the standards” (Drake & Burns, 2004).

The Common Core State Standards take a similarly holistic view of learning, with a call for integrating the English language arts and incorporating critical thinking and nonfiction reading across the curriculum.

Allowing students latitude in deciding how they will approach a project may also open the door for more interdisciplinary work, as students will naturally draw on the knowledge, skills, and interests they have developed in other studies and through life experiences.

LOOK FOR AUTHENTIC CONNECTIONS

The project planning stage is the time to look for genuine connections between disciplines. Avoid the PBL pitfall of “tacking on” a little bit of content from another subject area once you already have a project well underway.

For an example of real interdisciplinary work, consider a project designed by art teacher Jeff Robin and physics teacher Andrew Gloag. Their 12th-graders at High Tech High published a book called Phys Newtons, an illustrated guide to the California State Physics Standards (Robin, 2011). As preparation, each student researched one of Newton’s laws (motion, gravity, energy, circular motion, or projectiles). Students then painted images to visually demonstrate the law (while also meeting standards for visual arts). Each student designed a page of the book using a combination of images and text. A page explaining Newton’s Second Law, for instance, features a series of images showing a baseball player going through the motions of pitching. Accompanying text explains the relationship between force and acceleration. In an authentic performance assessment, students used their book—relying on both science and art—to teach their peers about Newton’s laws.

Exercise: Picture Career Connections

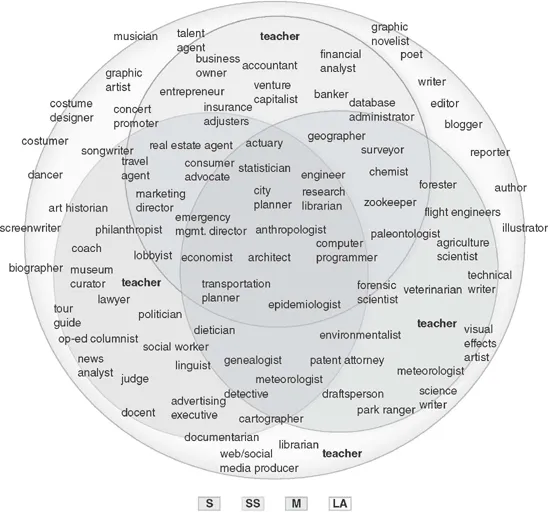

Many of today’s students are likely to enter career fields that overlap one or more disciplines. Take a close look at the Venn diagram in Figure 6.1. It shows overlaps between various careers and the four core content areas. You’ll notice that the English language arts are represented in this model as common ground. Being able to communicate and explain your thinking is essential in every field.

Think about the current interests of your students. Which career opportunities mesh with their passions? How could a project give them a chance to explore these career fields now?

Think, too, about the careers you don’t see represented here. New specialties are emerging all the time. What kinds of thinkers will be needed for future careers in computational biology, food politics, cybersecurity, or space travel? How could projects prepare students for these opportunities?

Figure 6.1 Venn diagram shows overlap between core content areas and careers. Language arts (LA) is represented as the “common ground” for each of the other three: social studies (SS), mathematics (M), and science (S).

WHAT’S NEXT?

In the next four chapters, we take a close look at inquiry in each of these core content areas: language arts, social studies, science, and math. You will hear from experts working in each discipline about what...