![]()

Part I Foundations for Everyday Courage

![]()

Chapter 1 What Is Everyday Courage?

The courage of life is often a less dramatic spectacle than the courage of a final moment, but it is no less than a magnificent mixture of triumph and tragedy. People do what they must—in spite of personal consequences, in spite of obstacles and dangers and pressures—and that is the basis of all human morality.

—John F. Kennedy

The Evolution of Courage

Early Greek philosophers, Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates, participated in spirited debates about the definition of courage. They were in agreement that courage was one of four virtues. The four virtues are prudence, justice, temperance, and courage. Aristotle is credited with saying that courage is the first of all virtues. It makes all other virtues possible. It was Socrates who asked, “What is courage?” He spent many hours with his students attempting to discover the answer to this question.

Plato’s ideas about courage, found throughout his writings, liken courage to a kind of perseverance. He took into account and considered how courage related to everyday common activities such as facing sickness, poverty, pains, and fears. Aristotle’s definition of courage was focused on physical courage, the courage of soldiers on the battlefield or the courage of men in defense of their families, and the role they play in keeping the polis, or city, safe. Aristotle’s conception of courage was that courage as well as the other virtues represented a system of means between extremes. With courage, the two extremes were cowardice and rashness. A coward runs away in the face of danger, as opposed to the extreme of rashness, which is when a person faces danger in a careless or foolish manner. Courage is the mean between the two. After the many debates and discussions however, Socrates and Plato lamented that they never arrived at a definitive answer to the question, “What is courage?”

Throughout the centuries, ancient and modern peoples have attempted to define and understand courage. Philosophers, soldiers, and common citizens alike have struggled to understand what it is about an action that makes it courageous (Brafford, 2003, p. 1). Although the definitions of courage and courageous acts have evolved over thousands of years, some ideals have remained true—people want to be considered courageous, and courage is highly valued by nations. All around the globe, nations recognize and bestow honor upon those who are thought to have performed courageously. In the United States, honors for courage include the Medal of Honor, which is the highest honor given to recognize valor in American armed forces, the Profiles in Courage Award, which recognizes displays of courage described in Profiles in Courage by John F. Kennedy, and the Civil Courage Award, which is a human rights award given by the Trustees of The Train Foundation for steadfast resistance to evil at great personal risk. In Sweden, the Edelstam Prize is given to persons for exceptional courage in standing up for one’s beliefs in the defense of human rights.

In modern America, beloved poet, novelist, and civil rights activist Maya Angelou reiterated the thinking of the early philosophers in many of her poems, stories, speeches, and interviews. She said,

I am convinced that courage is the most important of all the virtues. Because without courage, you cannot practice any other virtue consistently. You can be kind for a while; you can be generous for a while; you can be just for a while, or merciful for a while, even loving for a while. But it is only with courage that you can be persistently and insistently kind and generous and fair. (Beard, 2013)

Upon Angelou’s death in 2014, Washington Post writer Jena McGregor concluded,

The world lost a great author, poet and civil rights activist Wednesday when Maya Angelou died at her home in Winston-Salem, N.C. It also lost someone who was a great student of leadership and the creative process—who understood what it takes to have the courage to lead, who had close affiliations with some of the most well-known world leaders of her lifetime, and who could articulate the virtues of courage, steadfastness and truth as only a poet can do.

Angelou wanted to be known as a courageous person, and as she passed at the age of 86, she was lauded for her many accomplishments, most notably her courage.

Modern Science Studies Courage

Courage continues to intrigue human beings in the 21st century, over 2,000 years after Plato and Socrates failed to gain consensus on courage and courageous behavior. According to a collection of research studies on courage published by the American Psychological Association, titled The Psychology of Courage: Modern Research on an Ancient Virtue (Pury & Lopez, 2010), there is growing interest in courage and the quest to answer the question, “What is courage?” The study of courage is gaining momentum in the fields of psychology and neuroscience with over half of the research to date being done from 2000 to the present. The ultimate goal of the researchers, however, extends far beyond the early philosophers’ question and broadens to the following questions:

Why does courage matter?

Can courage be learned?

Can courage be leveraged to improve organizational performance?

As part of the research chronicled in this text, a synthesis of the many descriptions and definitions of courage proposed in the fields of philosophy, social sciences, literature and lexicons, was provided. (Pury & Lopez, 2010, pp. 52–53)

After extensive consideration of the descriptions and definitions, I am choosing to use the definition offered by Rate, Clark, Lindsay, and Sternberg (as quoted in Pury & Lopez, 2010) to define everyday courage for school leaders. When I speak of everyday courage throughout the book, it will be defined as (a) willful, intentional act; (b) executed after mindful deliberation; (c) involving objective substantial risk to the actor; (d) primarily motivated to bring about a noble good or worthy purpose; (e) despite, perhaps, the presence of the emotion of fear. In essence, courageous actions include risk, fear, purpose, and deliberate action, all of which are relatable and necessary in the day-to-day challenges of school leadership.

Further, contemporary thinking about courage encompasses all areas of modern life and contains the notion that there are many different kinds of courage, much like Plato’s early thinking on the subject. According to Steven Kotler (2011), author, journalist, and writer for Psychology Today, there are many types of courage in modern society. In his blog, “Courage: Working Our Way to Bravery: A Modern Examination of the Real Requirements of Fortitude,” he describes physical courage, battle courage, moral courage, intellectual courage, empathetic courage, emotional courage, fiscal courage, stamina, and decision making.

Everyday Courage for School Leaders Defined

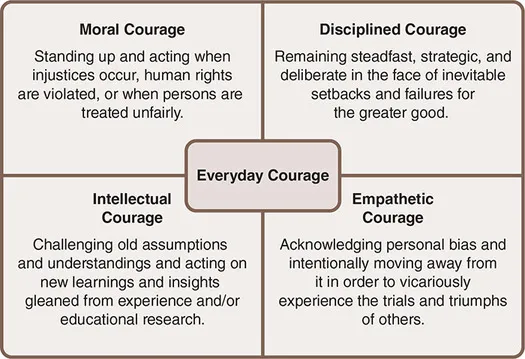

In relationship to the everyday courage needed for school leaders, I am borrowing from Kotler’s moral courage, intellectual courage, and empathetic courage, and adding disciplined courage to provide a description of everyday courage relevant to school leaders. Figure 1.1 provides an illustration of the four domains of everyday courage for school leaders as well as thumbnail definitions of each of the four domains of everyday courage.

Figure 1.1 Domains of Everyday Courage

In the following sections, the domains of everyday courage are discussed in greater detail to clarify and explain each one as it relates to the work of school leaders. I have included an illustrative example in each section in the principal profiles. These profiles convey the stories and experiences of principals like you who demonstrate everyday courage.

Moral Courage

Moral courage is the courage to stand up for one’s beliefs in the face of overwhelming opposition. It is a synonym for civil courage. Those with moral courage stand up and speak out when injustices occur, human rights are violated, or when persons are treated unfairly. Moral courage is the outward expression of the leader’s personal values and core beliefs, and the resulting actions are focused on a greater good. According to the research, what distinguishes moral courage is brave behavior accompanied by anger or indignation, which intends to enforce society or ethical norms without consideration for one’s own negative consequences (Greitemeyer, Osswald, Fischer, Kastenmueller, & Frey, 2006). It is best exemplified by the actions of people such as Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, or Rosa Parks.

As it relates to moral courage for school leaders, Leithwood, Harris, and Hopkins (2008, p. 28) point out that principals can have an impact on pupil learning through a positive influence on staff beliefs, values, motivation, skills, and knowledge, and ensuring good working conditions in the school, and that these factors all contribute to improved staff performance. They further report that in recent studies in the United States and United Kingdom, what stood out among the leaders who undertook the challenge of taking on very difficult-to-serve schools was their “‘moral purpose,’ a fundamental set of values centered on putting children first and faith in what children can achieve and what teachers can do.” The moral purpose of improving the lives of children is ever-present and directs the leaders’ actions and decisions toward that end. In short, moral courage for school leaders acts in service to all students.

For school leaders, it might involve intervening in and changing school practices that overidentify African-American male students for inclusion in special education, or it could involve maintaining persistence in dismissing a teacher who has been doing educational harm to students and previous leaders have failed to act and failed to spare students a wasted year in their learning. Moral courage compels action that ensures the social, emotional, and academic well-being of all students. Finally, moral courage is inclusive of several other types of courage and as such is an essential component of everyday courage in school leadership.

The Principal Profile that follows provides a rich example of moral courage from Tommy Thompson of Connecticut.

Principal Profile

Moral Courage

Tommy Thompson

New London, Connecticut

When Tommy Thompson became the principal at New London High School in New London, Connecticut, he observed many practices that challenged his moral compass. New London serves 977 students, where 80% are students of color and 70% are economically disadvantaged. There was an entrenched faculty that operated on a “this-too-shall-pass” mentality and an unspoken agreement of “you leave us alone and we will leave you alone.” Students were not graduating prepared for the rigors of college and careers, and they were not being challenged academically in their classes. The school ran as a factory model with all students receiving the same instruction regardless of their needs or entry level knowledge and skills. During our interview, Tommy stated, “Free agency among teachers abounded.” As the father of four sons, he knew this was not something he could accept. He felt, and continues to feel, a moral obligation to the parents of his students, and committed to do all he could to transform the culture of the school to embrace a students-first, equity-based mindset.

Tommy understood that if things were going to change, it meant that he had to be the change agent on behalf of the students, and he also knew that change agents don’t last long in the job. He stated to me during our interview, “you have to do a gut check and be able to look yourself in the mirror and say, ‘if this means I will only be here a short time then so be it.’” He could not accept the status quo, knowing that students were at risk ...