In telling this story, we share both the successes and challenges NJNS faced in integrating the work of equity and instruction. The practice of equity visits evolved over time, and it continues to evolve as NJNS furthers its exploration of equity in diverse district contexts and as individual districts develop their own equity visit practices. Equity is not a goal to achieve but a constantly moving target as demographics, education policy and politics, and instructional practices shift. For this reason, equity visits as a leadership practice require continual reflection and refinement. Our story highlights how a group of superintendents and members of their leadership teams came together to identify and address systemic inequities within their state and district contexts.

Missing: The Integration of Equity and Instruction

Observing classroom instruction and analyzing data for disparities are two common and important practices of educational leadership. In classroom observations, administrators and teachers regularly spend time observing teaching and learning as part of instructional rounds, classroom walk-throughs, teacher evaluations, and other initiatives. Often, classroom visits focus on a specific aspect of instruction, such as a dimension from a teacher evaluation framework, with the goal of building shared understandings of what this dimension looks like or should look like in practice. Visits may be used to ensure that teachers are implementing a particular curriculum or instructional strategy with fidelity. Following the observations, educators may share notes to determine if they had observed and assessed instructional practice in similar ways. Observers may also debrief the lesson with the teacher or analyze data collected across classrooms.

Another common practice is for schools and districts to disaggregate student performance data on statewide and school- or district-created assessments; sometimes this analysis includes other data sources such as discipline logs or attendance and graduation rates. In faculty meetings or professional development sessions, teachers and administrators examine data to identify patterns related to students’ demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, race, or special education status), as well as patterns related to structural features, such as teacher assignments, grade level, subject area, and even specific standards. They look for inequitable student outcomes and consider the potential reasons for disparities in achievement.

These two school practices are both important: Educational leaders need both a solid understanding of effective teaching and learning and the ability to identify and address inequitable student opportunities and outcomes within their schools. However, these practices often are conducted in isolation from each other. Instead of pursuing instruction or equity on parallel tracks, what is needed is an approach that integrates them. As Theoharis and Brooks (2012) argue, “It is not enough to work to improve curriculum and instruction in a general sense; it is essential to increase access, processes, and outcomes through improved instruction” (p. 5). They go on to suggest that effective, equity-focused leaders must ground their work “in educational, indeed instructional access, process, and outcomes” (p. 6). Efforts to improve instruction almost never impact persistent systemic inequities without explicit and sustained attention to these. Despite the pressing need, there are few resources that focus attention on instruction and equity.

Even though widespread disparities in educational opportunities and outcomes are not new, educators often view equity as something in addition to the work—not the foundation of the work (García & Guerra, 2004). As we illustrate in this chapter, equity can be an elusive target even among committed leaders who aim to make it the focus for their leadership practice.

The first part of the equation, leadership that focuses on improving instruction, is a well-established goal. Instructional leadership, a concept initially derived from the effective schools literature and focused on directive actions from the principal to the teachers, has expanded to include notions of transformational leadership (Hallinger, 2003). Hallinger (2003) described this evolution:

As the top-down emphasis of American school reform gave way to the restructuring movement’s attempts to professionalise schools in the early 1990s, transformational leadership overtook instructional leadership as the model of choice. As the 1990s progressed, a mixed mode of educational reform began to evolve, with a combination of top-down and bottom-up characteristics. (p. 342)

In this reconceptualized instructional leadership, also referred to as learner-centered leadership, administrators work with teachers to implement change, recognizing that one individual cannot create the types of change needed to ensure success for all students. Practices such as instructional rounds (City, Elmore, Fiarman, & Teitel, 2009; Hatch, Hill, & Roegman, 2016; Roegman, Hatch, Hill, & Kniewel, 2015) offer one way to support the development of a shared understanding of teaching and learning.

In instructional rounds, administrators and teachers observe classrooms, paying close attention to the teaching, learning, and curricular content evident there. These observations, typically organized around a problem of practice related to instruction, are meant to develop participants’ understating of instruction and student learning and develop a common language for discussing and improving teaching and learning. Along with teacher evaluations, professional development, and curriculum development, instructional rounds engage leaders in discussions about instruction and student learning.

The second part of the equation, equity, is less well developed. Even in the context of developing instructional leadership, equity and related concepts such as social justice, diversity, and multiculturalism are rarely addressed. Theories of leadership, such as transformative leadership (Shields, 2010), that call on leaders to consider systemic inequities and act on them, are often discussed separately from theories that focus specifically on instruction. When leadership preparation programs or professional development sessions address issues of equity, they often do so in seminars, courses, or readings that stand apart from the day-to-day life of the school. For example, many leadership preparation programs include a single course on multiculturalism or social justice. In other words, equity is not explicitly connected to the work related to instruction (Marshall, 2004; Roegman, Allen, & Hatch, 2017). Parker and Villalpando (2007) demonstrate that educational policies for curriculum or instruction are more likely to perpetuate existing inequalities in students’ opportunities and outcomes than to address them. To truly address inequity, educational leaders need an explicit and sustained approach that makes equity explicit.

Shifting from Instruction to Equity and Instruction

NJNS’s development of equity visits illustrates how committed equity-focused leaders developed an explicit focus on equity within their work on understanding and improving instruction. NJNS began with a strong commitment to address systemic inequities, made explicit in its theory of action that “ALL MEANS ALL.” However, its early practice demonstrates how focusing on instruction can leave out paying attention to equity.

The key shifts we describe below were made possible by regular cycles of reflection on the part of NJNS’s design team and the network as a whole. Our reflections drew on Argyris’s (1977) concept of “double-loop learning,” an approach to organizational learning that requires practitioners to think critically about why initiatives succeed or fail and to question underlying assumptions. As part of NJNS’s practice as a learning community, design team and superintendent members regularly reflect on our learning about systems-level leadership related to equity, instruction, and progress related to our theory of action and norms (discussed in Chapter 3). As the story of the evolution of rounds into equity visits illustrates, this continual reflection allowed us to identify a set of essential ingredients to integrate equity with our work on instruction:

- Explicit, clearly articulated expectations for naming existing inequities in access and outcomes

- Disaggregated data, beyond year-end test scores, to understand the “hows” and “whys” of existing inequities in instructional practice

- Opportunities to reflect on and refine the work happening within schools

- Shared understanding of key terms and concepts, including instructional equity and equity-focused leadership

These “essentials” underlie NJNS’s evolution over time as equity-focused leaders worked to create school and district cultures that integrate equity and instruction.

Addressing the Challenges of Keeping Equity at the Center: Creating Equity Visits

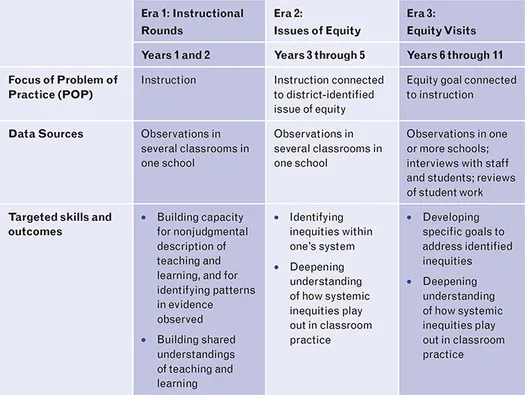

We describe NJNS’s shift to the use of equity visits in three “eras.” Throughout the three eras, NJNS regularly visited schools in participating superintendents’ districts and observed a range of problems of practice related to instruction and equity. While the design team and participating superintendents were deeply committed to equity in education, our ongoing reflection on NJNS’s activities made it clear that the practice of instructional rounds was not supporting the types of conversations needed for instructional improvement for all students, particularly students of color and other underserved students. These reflections prompted the changes from one era to the next. For each era, Figure 1.1 highlights changes in the focus of the visits, the types of data collected, and learning objectives for the participants.

Figure 1.1 NJNS Eras Examining Equity and Instruction

Era 1: Instructional Rounds

NJNS’s initial approach to rounds followed the example of the Connecticut Superintendents’ Network (CSN), facilitated by Richard Elmore and Lee Teitel (City et al., 2009; Elmore, 2007). In our first daylong meetings, we focused on developing participants’ skills as non-judgemental observers of instruction, and on developing a common understanding of teaching and learning. Each rounds visit was hosted by a superintendent who selected a school within their district to be the focus. The host, along with various members of their leadership team, developed a problem of practice for the visit, an issue or challenge directly related to instruction. (See Chapter 2 for a more detailed explanation of terms such as problems of practice, look-fors, patterns, and wonderings.) Before entering the classrooms to observe, the host shared a brief presentation about the problem of practice, as well as relevant data, such as demographics and test scores. The host outlined a series of “look-fors”—specific elements of instruction related to the problem that guide the observation, such as “What evidence of students posing questions do you observe?” and “Are learning objectives visible in the classroom?” Then, for about two hours, in small groups, superintendents and design team members visited four to six classrooms for about 10–15 minutes each. In each classroom, they recorded observations related to the problem of practice and look-fors. Figure 1.2 presents an example of a problem of practice and set of look-fors from a rounds visit from Era 1; together, they highlight that era’s emphasis on instructional practice.

Figure 1.2 Sample Problem of Practice and Look-Fors from a Visit in Era 1 to Grover Middle School in West Windsor-Plainsboro Regional School District

After the classroom observations, the small groups reviewed their notes and identified patterns across classrooms related to the problem of practice. They also framed a small number of “wonderings,” also related to problems of practice, for the host team to think about. Each small group presented its patterns and wonderings to the whole group, as well as any district and school representatives invited by the host superintendent. Next, either in small groups or as a whole, superintendents developed and presented a series of recommendations for the host school. The day concluded with NJNS members reflecting on their learning about the instruction.

Over our first two years of instructional rounds practice, NJNS focused on developing superintendents’ abilities to be descriptive and nonjudgmental in their observations. This was meant to support leaders in understanding and discussing the complexities of instructional practice rather than simply or immediately evaluating it, a typical expectation for administrators. Samuel Stewart, retired county superintendent of Mercer County, shared a reflection during a rounds visit in Era 1 that was typical of the era: “It is the focus of rounds that makes it so powerful. I think it is taking one of key ideas of the instructional core, teacher, student, and content, and focusing on that.” In reflecting on the first years of NJNS, design team members and superintendents felt, like Stewart, that they were improving individually and collectively in their ability to observe and discuss cla...