![]()

Adaptations for Success in General Education Settings with Jill Hudson | 1 |

CASE STUDY: WILSON

Mrs. Blume announces, “Everyone, it is time to put your materials away and quietly line up for art class.” The students follow the teacher’s direction, closing their language arts books, putting their worksheets in their folders, placing the books and folders in their desks, pushing their chairs in and then quietly lining up at the door. Mrs. Blume, noticing that Wilson is still sitting at his desk reading his language arts book, asks, “Wilson, why have you not put all of your materials away and gotten in line like the rest of the children? You need to listen.” Wilson, not understanding why he is being scolded, shows his frustration by crying and throwing himself to the floor.

CASE STUDY: TALIA

The bell rings. Children rush through the hallway toward their lockers, to the restroom, to say hello to a friend. Quickly they shuffle along and return in a few minutes to the classroom, settling back into their seats and pulling out their work. With the teacher’s instruction, they quiet down and begin working. Talia comes stumbling through the door, dragging her backpack full of books behind her. As she makes her way to her seat, she bumps a couple of desks and says, “Hey, what are you guys doing? Did you see the guy in the hallway?” The teacher interrupts and redirects Talia to her seat. Talia nevertheless continues with her story, giving dramatic details and tripping over others as she makes her way to her seat. Once seated, she fumbles through her bag, pulling out her book with papers crammed inside. She blurts out loudly to her teacher, “Do you have a pencil?” Mrs. Smith closes her eyes and thinks to herself, “What am I supposed to do?”

Developed by: Jeanne Holverstott

These scenarios are all too familiar to many teachers. Children coming in late, not prepared with materials or work for the day, and interrupting with details irrelevant to class. With class size increasing and the needs of students continually diversifying, the typical classroom is often a challenge to manage.

Within each classroom, a certain level of expectation must be met in order for the class to run efficiently and effectively. However, expectations vary from teacher to teacher and across settings. Knowledge of expectations is critical for students to succeed in a particular classroom. Thus, their ability to predict, understand, and perform to the level required reflects on their achievement as well as their ability to advance. Nevertheless, while each teacher’s expectations vary, certain expectations that support a well-run classroom are consistent across grade levels. Expectations and other tools that are effective in the classroom are discussed in this chapter.

BEHAVIOR EXPECTATIONS

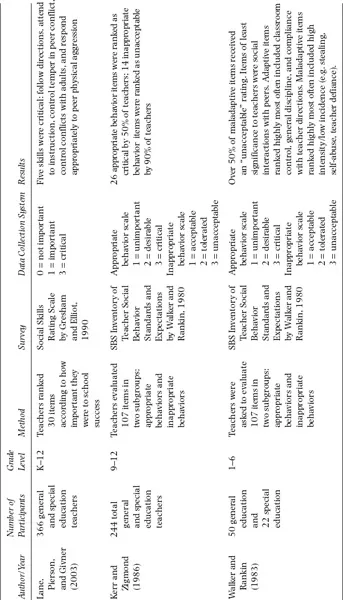

Studies conducted across all grade levels show that teachers consistently look for and expect similar classroom behaviors in spite of the grade level taught (Hersh & Walker, 1983; Kerr & Zigmond, 1986; Lane, Pierson, & Givner, 2003; Walker & Rankin, 1983). In addition, when they list undesirable or intolerable behaviors within the classroom setting, they are closely related as well. As shown in Table 1.1, the findings of research into teacher expectations suggest that teachers rate behaviors such as self-control, cooperation, overall discipline, and ability to follow teacher direction as most critical and more important than social interactions with peers and related behaviors.

While teachers agree overall on the behaviors that promote a positive learning environment, some differ depending on grade level. That is, elementary and high school teachers tend to value some behaviors differently (Hersh & Walker, 1983; Kerr & Zigmond, 1986; Lane et al., 2003; Walker & Rankin, 1983). For example, as shown in Table 1.1, overall, elementary-grade teachers place less value on items that relate to peer-to-peer relationships, such as initiating conversation with peers, while stressing the importance of behaviors that directly impact their interaction with students, such as following written and oral directions. Elementary-grade teachers generally consider half as many behaviors critical for the classroom as high school teachers, though they rank many as desirable. Table 1.2 compares the top 10 behaviors rated critical for classroom success by high school teachers with the top 10 of those teaching elementary grades. Though there are many similarities between the two lists, the degree to which behaviors are valued varies.

Table 1.1 Overview of Research on Student Behaviors in General Education Classrooms

Table 1.2 Teachers’ Perceptions of Essential Student Behaviors

High School

- Follows established classroom rules

- Attends to and follows oral instructions given for assignments

- Attends to and follows written teacher instruction

- Complies with teacher commands

- Completes assignments in class when required

- Responds appropriately to peer pressure pertaining to following classroom rules

- Produces work corresponding with ability and skill level

- Possesses effective classroom management skills—efficient, organized, on-task

- Requests assistance in an appropriate manner when needed

- Copes with failure in an appropriate manner

Elementary School

- Complies with teacher commands

- Follows established classroom rules

- Produces work corresponding with ability and skill level

- Attends to and follows oral instructions given for assignments

- Expresses anger appropriately

- Interacts with peers without becoming hostile or angry

- Regulates behavior in non-classroom settings

- Responds appropriately to peer pressure pertaining to following classroom rules

- Completes assignments in class when required

- Requests assistance in an appropriate manner when needed

A comparison of teacher tolerance across grade levels is also interesting. When provided a list of inappropriate behaviors, elementary-grade teachers ranked over half of the maladaptive behaviors as “unacceptable.” In comparison, only 14 behaviors were rated “unacceptable” by at least 90% of the high school teachers. So while the high school teachers demand more, the elementary-grade teachers tolerate less. Table 1.3 compares the maladaptive behaviors most often rated “unacceptable” by high school teachers and by elementary teachers.

While understanding behavioral characteristics is important, one must also realize that the image each student projects impacts how teachers and others perceive them and interact with them. Richard Lavoie (cited in Bieber, 1994) has outlined several characteristics that should be taught to all students in every classroom because they are held in high esteem by adults and student peers.

- Smiling and laughing. All children enjoy seeing another child smile. It is contagious and keeps the atmosphere of the room light and positive.

- Greeting others. Teach the students to say hello to others as they pass in the hallway. It is friendly and encourages students to keep their heads up as they change classes.

- Extending invitations. When students are going out together or starting an activity, encourage them to include others and to always look for additional participants.

- Conversing. Communication skills are important to express, request, and comment on a variety of scenarios throughout the day. Help students understand the basic rules of communication, how to initiate a conversation and take turns, and how to take interest in others.

- Sharing. No one enjoys a student who keeps everything to himself. Encourage students to work together and collaborate on projects and share supplies.

- Giving compliments. Everyone enjoys knowing what is special about him or her. Make a point to express when a student does something well or when he or she is appreciated.

- Good appearance. Hygiene and grooming are important for self-esteem, cleanliness, and positive interactions among peers.

Table 1.3 Teachers’ Perceptions of Inappropriate Classroom Behaviors

High School

- Engages in inappropriate sexual behavior

- Steals

- Is physically aggressive against others

- Behaves inappropriately in class when corrected

- Damages others’ property

- Refuses to obey teacher-imposed classroom rules

- Disturbs or disrupts the activities of others

- Is self-abusive

- Makes lewd or obscene gestures

- Ignores teacher warnings or reprimands

Elementary School

- Steals

- Is self-abusive

- Retaliates in class when corrected

- Is physically aggressive with others

- Makes lewd or obscene gestures

- Engages in inappropriate sexual behavior

- Refuses to obey teacher-imposed classroom rules

- Damages others’ property

- Throws tantrums

- Ignores teacher warnings and reprimands

Lavoie has also outlined a list of behaviors that will help students be successful. He calls this list the “No Sweats,” as they take relatively little time to learn as well as minimal effort and energy to do.

- Be on time.

- Establish eye contact when speaking or listening.

- Participate, either by giving input to a discussion or simply by asking a question.

- Use the teacher’s name.

- Submit work on time.

- Use the required format for assignments and projects.

- Avoid crossing out on papers.

- Request explanations instead of giving up when not understanding.

- Thank the teacher for his or her effort and time.

If these skills and behaviors are taught in the classroom and included as expectations, a general education classroom can be expected to run more harmoniously.

CONSISTENCY AND CLEAR COMMUNICATION OF EXPECTATIONS

Communication of expectations is the key (Backes & Ellis, 2003). Often students “misbehave” because they do not clearly understand what is expected. Three to five classroom rules may be posted that contain items such as “Be courteous.” Without a specific definition of what that rule entails, it is left open to a variety of interpretations and may be widened or narrowed according to each child’s personal analysis. In addition to general classroom behavior, expectations are assumed for personal conduct, safety, and assignments and should be clearly outlined or stated to ensure understanding. Since many students move through several teachers and classrooms in a given day, it is helpful to define, set, and uphold expectations in a similar manner.

Members of the same profession do not always agree on expected outcomes. Therefore, those who interact with the child need to determine what is desired by all team members so that when individual members teach students about appropriate behaviors, the students are meeting the larger set of expectations across all settings.

EXPECTATIONS IN PRACTICE

Teacher expectations must be translated into rules and routines that students understand. Most students without disabilities are able to infer these expectations. However, for many students with disabilities, teacher expectations remain a mystery. General education expectations can be operationalized into four groups: (a) response to teacher, (b) interactions with peers, (c) self-regulation, and (d) classroom performance. These expectations are not always easy to follow or understand when they are not explicitly written out or taught. Often rules are posted, but expectations are inferred and vary from task to task. Therefore, to maintain and perform at a level consistent with the general expectations that fall into these four categories, students must use combined components from social, communication, and cognitive domains. For some children, performing to desired expectations poses a genuine challenge. Having to pay attention to only one component at a time prevents them from being able to multitask and perform consistently at the level expected without supports from the school environment. Students with Asperger Syndrome (AS) fall into this category.

Response to Teacher

Response to the teacher is defined as those behaviors that directly relate to the instructor. Listening to teacher instructions, complying with requests, asking questions, and seeking help appropriately fall into this category.

Listening to Teacher Instructions and Complying With Requests

Students with AS generally process directions and instructions better when given in a concrete, visual manner. Therefore, when instructions are given only verbally they are often not able to accurately process and follow them. In the first case study above, Wilson is unable to process Mrs. Blume’s verbal directions. Mrs. Blume, not understanding that Wilson has difficulty processing verbal instructions, thinks he is misbehaving and scolds him. Wilson does not understand why he is being scolded because he had not heard the instructions. He begins to cry and falls to the floor. However, when Wilson was unable to get started on his math assignment, Mrs. Smith wrote the directions on the paper in three steps in addition to verbally stating it. After receiving written instruction, Wilson was able to complete the assignment with little additional assistance.

Asking Questions and Seeking Help Appropriately

When a student with AS needs a pencil, other class supply, or assistance, he may blurt out the request without paying attention to the context of the situation—that is, that students are to raise their hands to get the teacher’s attention. In the second case study, Talia has disrupted class and she blurts loudly that she needs a pencil instead of quietly raising her hand until the teacher calls on her. By learning a method through which to make the request (i.e., raising her hand), the student has an outlet to receive what she needs in a manner that complies with the environment.

Interaction With Peers

Interaction with peers consists of behaviors such as conversing with and relating to peers and collaborating with peers.

Conversing With and Relating to Peers

Communication and interaction with peers can be a great challenge to students with AS because they often lack skills to detect facial cues and other nonverbal cues and fail to understand social subtleties. In addition, depending on their special interests as well as developmental level, students with AS may or may not relate to their same-age peers. Thus, some students may need instruction and support in learning how to join a group of children and suggestions for how to maintain intera...