eBook - ePub

Cap-Analysis Gene Expression (CAGE)

The Science of Decoding Genes Transcription

- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is a guide for users of new technologies, as it includes accurately proven protocols, allowing readers to prepare their samples for experiments. Additionally, it is a guide for the bioinformatics tools that are available for the analysis of the obtained tags, including the design of the software, the sources and the Web. Finally, the book provides examples of the application of these technologies to identify promoters, annotate genomes, identify new RNAs and reconstruct models of transcriptional control. Although examples mainly concern mammalians, the discussion expands to other groups of eukaryotes, where these approaches are complementing genome sequencing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cap-Analysis Gene Expression (CAGE) by Piero Carninci in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Probability & Statistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Cap Analysis Gene Expression (CAGE)

Omics Science Center, RIKEN Yokohama Institute, Japan

Email: [email protected]

Cap Analysis of Gene Expression (CAGE), originally developed by our group, is used to perform a genome-wide survey of promoters. Our group is primarily engaged in transcriptome analysis and has developed fundamental technologies required for such analysis. In addition, we have developed a full-length cDNA selection method known as the Cap Trapper method (see Chapter 2) that is one of the fundamental technologies for CAGE. In CAGE, the 5’-CAP of mRNA is obtained using this full-length cDNA selection method, or Cap Trapper. From the 5’ end of mRNA, which is a product of transcription, 20-base pair are collected as tags using Type IIS restriction enzymes and the tag sequence is determined by sequencing. Incidentally, we have recently developed a technique producing 27-base pairs long tags. The obtained tags can identify promoter sites by mapping model organism genomes to the human. Furthermore, by investigating the expression frequency of the tag mapped to each promoter site, we can measure the transcription activity of promoters. Thus far, CAGE has been the main method for identifying promoters and determining their activity at the genome-wide level.

An analysis of promoters is essential if we are to understand the gene network that comprehensively explains life phenomena at a molecular level. In the international project called Functional Annotation of Mammalian cDNA (FANTOM3), more than 230,000 mouse promoters were identified by CAGE, and on average that represents approximately 5 promoters for each gene, and therefore the same number of transcription start sites. We are currently engaged in the FANTOM4 project through which we aim to link genes to phenotypic characteristics at the genome level. Since systems biology and gene network analyses require promoter-based analysis, CAGE will become increasingly important in the future.

In recent years, $100,000 genome technology has been accomplished and it is not long before we reach $1,000 genome-sequencing technology. Despite a relatively short read length of 30–100 bases, companies such as 454 (Roche Diagnostics), Solexa (Illumina), SOLiD (Applied Biosystems) and Helicos have rapidly commercialized their own sequencers based on different technologies. As it stands, all of these technologies allow sequencing of a large number of reads: 300,000 to 500,000,000 in a massively parallel way. Often the read length of these technologies is short, so we need to optimize the assembly of trace sequences to determine de novo sequencing of genomic DNA. However, current sequencers are certainly effective for the human genome, where the full-length sequence has already been determined. Furthermore, unlike a traditional cDNA sequencing project, the produced sequence does not identify the correspondence of expressed tags with the original mRNA, and direct use of these data for full-length cDNA sequence reconstruction is difficult. However, these sequencing technologies are very effective for CAGE because it does not require assemblies of full-length cDNA sequences. Since each produced sequence is a tag, all information can be obtained by simply mapping such tags onto the genome. With such massively parallel sequence technologies and the dramatic increase in throughput, it is possible to achieve quantitative analyses of gene expression by measuring the number of tags mapped to each promoter. It is not an exaggeration to say that $1,000 genome sequencing technology is conceivable when combined with CAGE. A massive parallel shotgun sequencer with the ability to produce an enormous number of tags can easily sequence 1,000,000 to 10,000,000 tags per cell in a run. If this is applied to a CAGE library from one tissue, it is theoretically possible to identify and measure RNA molecules at a molecule for each 1 to 10 cells with a probability of greater than 99.9%. Therefore, CAGE-based analysis has entered a completely new phase thanks to these sequencing technologies. In the FANTOM3 research released in 2005, CAGE data was used mainly for genome-wide identification of transcription start sites. Such data provide an extremely useful tool for linking expression analysis to network analysis in the current FANTOM4 analysis ongoing at Omics Science Center and at collaborative facilities.

The trend is gradually moving from genome and transcrip- tome analyses to the molecular description of life phenomena. This may also allow systems biology to systematically cover all molecules inside the living body. In this era, promoter analysis becomes very important and represents an essential analytic target for the investigation of the networks that regulate life phenomena. After our cDNA discovery research (FANTOM1 and 2) using full-length cDNA technology and promoter discovery (FANTOM3) achieved by CAGE, next-generation research in FANTOM4 is about to explain certain cellular conditions with transcription factors. CAGE is one of the key technologies of a pipeline called Life Science Accelerator (LSA) for describing molecular networks that link genes to phenotypes in a computational and combinatorial way.

Both CAGE and SAGE produce fragments of RNAs as tags and determine their sequences. However, the concept behind each is completely different. SAGE was originally developed to obtain frequency information of the number of specific sequences (tags) that appear from the recognition sites of restriction enzymes in the mRNA pool. The one-to-one correspondence between SAGE tags and mRNA/cDNA are thus defined by the sequences of the restriction enzymes used for cDNA cutting and the length of the produced sequences using Type IIs restriction enzymes, like MmeI, 20 nt. However, the frequencies of SAGE tags reflect the overall expression frequency of all RNAs containing the tag sequences, regardless of their alternative promoters and splicing. Thus, SAGE does not uncover various promoters of genes and associated transcription activity, nor is it able to measure the number of molecules per RNA (per RNA isoform).

Conversely, CAGE was developed to determine the position of the genome from which RNAs are transcribed. In other words, this technology identifies the core promoter sites of each gene on the genome. Since the tags start from the CAP sites in CAGE, we can identify transcription start sites by mapping the tag to the genome sequence. SAGE can identify the existence of certain expressed sequences, but it cannot differentiate whether the sequences are derived from one or more transcripts or are regulated by various promoters; therefore, SAGE only achieves overall expression information. In this sense, information obtained by SAGE is similar to microarrays. Conversely, information obtained by CAGE indicates the number of molecules produced by each transcription start site. Significantly enough, in CAGE, promoter activity at each alternative “first” exons is identified with the number of the detected tags. In other words, CAGE is the only method that analyzes expression activity at each promoter.

In general we would like to address two major biological questions:

(1) How is production of RNAs regulated?

(2) What kinds of RNAs are produced?

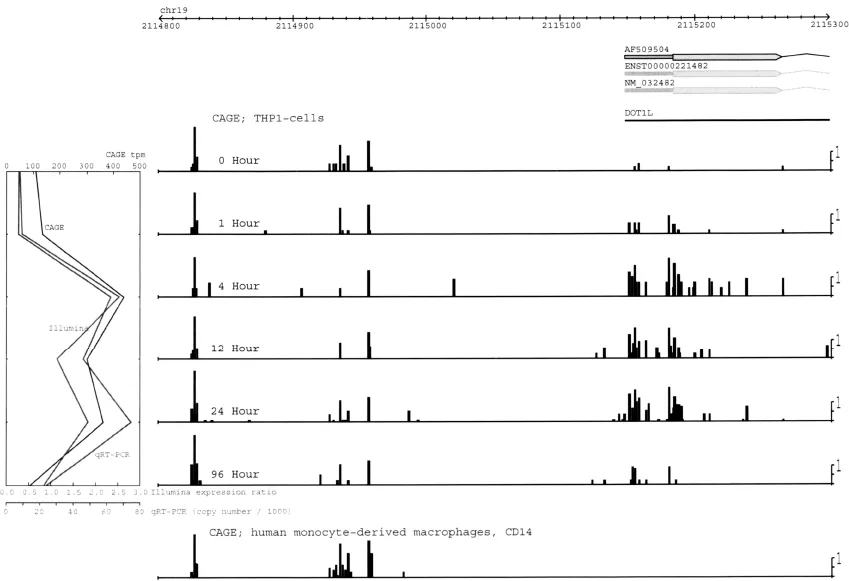

For the first question, we can obtain information by CAGE analysis. For the second, we need synthesis of full-length cDNA and their sequencing. Figure 1.1 shows the advantage of CAGE in measuring regulation by upstream promoters. In a comparison of normal and cancer cells, CAGE is used to show the significant differences in the activity of upstream promoters.

For the first question, we can obtain information by CAGE analysis. For the second, we need synthesis of full-length cDNA and their sequencing. Figure 1.1 shows the advantage of CAGE in measuring regulation by upstream promoters. In a comparison of normal and cancer cells, CAGE is used to show the significant differences in the activity of upstream promoters.

At present CAGE does need 25–50 μg of RNA for quantitative analysis. One of our next targets is to reduce the amount of sample needed for CAGE analysis. Ultimately, we should be able to detect the products of a single cell. This is because conditions of cells vary depending on each cell and if more than one cell is targeted for CAGE measurement, we can only obtain averaged results and thus cannot uncover unique activity at the cellular level.

In the following, we discuss the rapid improvements in the analytical capability of CAGE and explain the principles underlying the technology and associated details of data analysis and applications.

Figure 1.1. Core promoter activity identified by CAGE. CAGE tags are represented by blue vertical bars, mapping at different positions on the genome. CAGE identifies activity of normal tissues (left) and cancer-specific promoters (right). The 6 horizontal lines identify different CAGE libraries from the THP-1 cell line.

Chapter Two

Tagging Transcription Starting Sites with CAGE

Omics Science Center, RIKEN Yokohama Institute, Japan

Email: [email protected]

The output of the genome is much more complex than previously thought. The number of transcription starting sites exceeds by at least one order of magnitude the number of protein-coding genes. CAGE is the only technology to address such transcriptional variability, allowing identification of promoter and the detection of their activity, as well as the detection of novel species of non-protein coding RNAs. CAGE technology provides specific information that cannot be obtained with other transcriptome approaches.

2.1 THE OUTPUT OF THE GENOME IS COMPLEX

In present-day biology textbooks the workings/function of the mammalian genes are/is explained in a fairly simple/elementary and straightforward manner. In a such view, a typical gene transcribes a messenger RNA (mRNA) encoding one or sometimes multiple protein isoforms by alternative splicing. Generally, gene expression is depicted as being driven by a single promoter. Except for splicing, 5’ end capping, and 3’ poly-A tail addition, there are few conceptual differences in the description of prokaryotic and eukaryotic RNA outputs. However, recent studies have challenged this notion of mammalian gene structure and demonstrated that the output of mammalian genomes is much more complex than previously thought. In fact, the complexity of the organ and tissue development in the animal kingdom, including the nervous system, is associated with a parallel increased complexity of the genome output in terms of RNA complexity and diversity. This includes a plethora of different RNAs from individual loci, including non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). Indeed, loci encoding for known proteins also produces multiple transcripts that often originate at different positions in the genome. This includes alternative promoters and promoters inside known gene elements (internal exons, introns as well as 3’ untranslated regions, or 3’ UTRs).1,2 Moreover, many large non-protein-coding RNAs have also been broadly identified in mammalians,3,4 and these are often transcribed in a direction opposite to previously known transcripts, otherwise known as antisense (AS) RNAs.5 The emerging picture, which is still far from complete, is that mammalian genomes can be seen as “RNA machines”. This is a concept that is dramatically different than that presented in today’s textbooks where the genome is described as a repository of information encoding for proteins. The traditional idea is that proteins derive from the translation of a relatively few species of mRNAs, which are generally produced from a well defined starting site of a single promoter. Instead, this simplistic pattern is true only for a minority of mammalian genes. In fact,

(1) more than half of the genes have alternative promoters;

(2) even defined promoters show multiple transcription initiation sites over a broad span of 50–100 base pairs of core promoters;

(3) an even larger number of genes show alternative splicing;

(4) more than half of the transcriptional units encoded in the genome are constituted by non-coding RNAs;

(5) at least 72% of genes show sense-antisense transcription, often involving non-coding RNAs;

(6) mammalian cells contain a multiplicity of short RNA variants of large RNAs.6 Such complex patterns of multiple and different RNAs produced by each locus are challenging our image of what constitutes a gene product, and ultimately what constitutes a gene.

Although it is still very informative to analyze the transcriptome with conventional approaches, i.e., using microarrays for simple eukaryotes (like yeast) without dramatically compromising the identification of various overlapping mRNA, but more complex eukaryotes, and in particular vertebrates, show a much large number of transcripts and variants originating from different positions of the same locus. Therefore, predicting all the various RNA products and their transcription starting sites, including the alternative promoters, is impossible without a dedicated approach like CAGE, which has been instrumental in revealing such complexity.4,7,1

Indeed, the CAGE technology addresses multiple questions in the transcriptome analysis:

(1) How can we comprehensively identify the transcriptional starting sites (TSSs) and therefore the core promoter elements?

(2) How can we identify the nearby genomic regions that act as core promoter elements?

(3) How can we identify the RNA starting sites that are tissue- and cell-specific?

(4) How can we connect specific transcription starting sites with the regulatory network behind the specific RNA expression in tissues, cells, or other biological conditions?

(5) How can we also identify and profile various capped RNAs, including ncRNAs and antisense RNAs and their controlling elements?

We will address these questions herein and provide more detail in the chapters describing bioinformatic and biological analyses.

2.2 MAPPING 5’ ENDS: FROM ESTS TO TAGGING TECHNOLOGIES

Initial genomics-based approaches for large scale mapping of transcription starting sites (TSSs) have been based on the preparation of full-length cDNA libraries, followed by the sequencing of expressed sequencing tags (ESTs) from their 5’ ends and alignment to the human genome.8 The strategy underlying this approach is as follows: if multiple 5’ end sequences of full-length cDNAs can be aligned at nearly overlapping positions on the genome, they are likely to identify t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Cap Analysis Gene Expression (CAGE)

- 2. Tagging Transcription Starting Sites with CAGE

- 3. Construction of CAGE Libraries

- 4. Transcriptome and Genome Characterization Using Massively Parallel Paired End Tag (PET) Sequencing Analysis

- 5. New Era of Genome-Wide Gene Expression Analysis

- 6. Computational Tools to Analyze CAGE — Introduction to PART II

- 7. Extraction and Quality Control of CAGE Tags

- 8. Setting CAGE Tags in a Genomic Context

- 9. Using CAGE Data for Quantitative Expression

- 10. Databases for CAGE Visualization and Analysis

- 11. Computational Methods to Identify Transcription Factor Binding Sites Using CAGE Information

- 12. Transcription Regulatory Networks Analysis Using CAGE

- 13. Gene-Expression Ontologies and Tag-Based Expression Profiling

- 14. Lessons Learned from Genomic CAGE

- 15. Future Challenges in CAGE Analysis

- 16. Comparative Genomics and Mammalian Promoter Evolution

- 17. The Impact of CAGE Data on Understanding Macrophage Transcriptional Biology

- Color Index

- Index