eBook - ePub

Osmotic Dehydration and Vacuum Impregnation

Applications in Food Industries

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Osmotic Dehydration and Vacuum Impregnation

Applications in Food Industries

About this book

This volume in the Food Preservation Technology Series presents the latest developments in the application of two solid-liquid operations, Osmotic Dehydration (OD) and Vacuum Impregnation (VI), to the food industry. An international group of experts report on the improvement of osmotic processes at atmospheric pressure for fruits and vegetables, cu

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Osmotic Dehydration and Vacuum Impregnation by Pedro Fito,Amparo Chiralt,Jose Manuel Barat,Walter E. L. Spiess,Diana Behsnilian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Engineering General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

OSMOTIC PROCESSES IN FRUIT AND VEGETABLES AT ATMOSPHERIC PRESSURE

CHAPTER 1

High-Quality Fruit and Vegetable Products Using Combined Processes

INTRODUCTION

CONSUMER demand has increased for processed products that keep more of their original characteristics. In industrial terms, this requires the development of operations that minimize the adverse effects of processing. At the moment there is a high demand for high-quality fruit ingredients to be used in many food formulations such as pastry and confectionery products, ice cream, frozen desserts and sweets, fruit salads, cheese, and yogurt. For such uses, fruit pieces must preserve their natural flavor and color, they must preferably be free of preservatives, and their texture must be agreeable. Proper application of “combined processes” may fulfill these specific requirements. These processes use a sequence of technological steps to achieve controlled changes of the original properties of the raw material (Maltini et al., 1993). In most cases, the aim is to obtain ingredients suitable for a wide range of food formulations, although end products can also be prepared. Although some treatments, e.g., blanching, pasteurization, and freezing, have primarily a stabilizing effect, other steps, namely, partial dehydration and osmodehydration, allow the properties of the material to be modified. Modification may include physical properties such as water content, water activity, and consistency, and chemical and sensory properties as well; the latter two are also associated with a change in composition. A partial dehydration step is useful to set the ingredients in the required moisture range, whereas a finer adjustment of water activity, consistency, sensory properties, and other functional properties is better achieved by what is generally called an “osmotic step,” i.e., a temporary dipping in a concentrated syrup. As is now well recognized, under this conventional term of osmosis, there is a more complex phenomenon that has been defined as “Dewatering-Impregnation-Soaking” in concentrated solutions. According to temperature, time, type of syrup, and surface and mass ratio of product to solution, the osmotic treatment can induce on the same raw material very different effects. Of primary importance are the ratio of water loss, mainly affecting consistency, to solute uptake from the syrup, affecting flavor and taste.

Despite the large number of theoretical and experimental studies, combined processes are still hard to find in the food industry, although there are some “confidential” applications. The general criteria, here outlined, could be a first help in the choice and management of the proper technology. As an example, results are summarized of researches conducted to evaluate the effect of both raw material characteristics and process parameters on texture, color, and vitamin C retention in frozen kiwifruit slices after processing and during frozen storage.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The first goal of the research was to obtain high-quality, high-moisture frozen kiwifruit slices for the preparation of frozen fruit salads. As a first step, the influence was studied of the ripening stage, and thus of the texture level of the raw fruit on the texture characteristics of freeze-thawed kiwifruit slices. Because there is a strong correlation between texture characteristics and pectic composition of fruits (Souty and Jacquemin, 1976), the different forms of pectins were analyzed on the basis of their different solubility: water soluble, oxalate soluble, and residual protopectin.

Kiwifruits, cultivar Hayward, were stored differently to obtain the following three texture levels: 4–5 kg (firm), 1.8–2.5 kg (medium), and 0.8–1.5 kg (soft). Osmotic dehydration in a 70% sucrose solution for 4 h at room temperature was used as a pretreatment considering the high sensitivity of kiwifruit color to air drying (Fomi et al., 1990). The osmodehydrated fruits were then frozen and stored at –20°C for 12 months. As for the osmotic step, the lower the texture level the lower the soluble solids gain, whereas the water loss value is higher in the firm fruits compared with that of medium and soft ones (Torreggiani et al., 1998a).

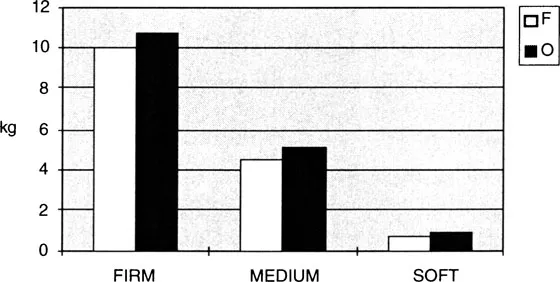

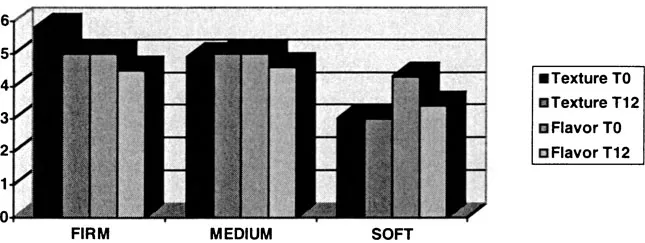

A slight increase of texture was observed in the osmodehydrated kiwifruits, which could be due to the simultaneous loss of water and gain of solids caused by the process (Figure 1.1). Firm, medium, and soft kiwifruit show percentage texture increase of 6%, 13%, and 17%, respectively.

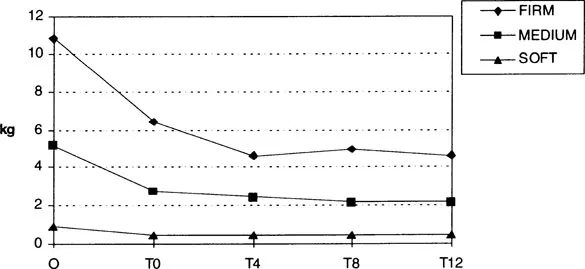

As shown in Figure 1.2, a significative decrease of texture due to the freezing process was observed (Torreggiani et al., 1998b). Firm, medium, and soft kiwifruit showed percentage texture decrease of 42%, 44%, and 62%, respectively, indicating a very poor suitability of the soft fruits. During the first 4 months of storage, texture of firm and medium fruits showed a further significant decrease. At the end of the 12 months of storage, the texture of the firm kiwifruits was still significantly higher than that of the medium and soft ones.

Figure 1.1 Texture values of kiwifruit slices before (F) and after (O) osmotic dehydration (Torreggiani et al., 1998a).

The analysis of the pectin composition confirmed the major role of the protopectin in tissue firmness (Shewfelt and Smit, 1972), as shown in Figure 1.3.

Furthermore, residual protopectin (R) degradation observed during freezing in firm and medium kiwifruit (Figure 1.3) could be regarded as one of the causes of the texture reduction observed in the freeze-thawed fruits. A direct correlation (R2 = 0.92) was found between texture of the raw fruit and texture acceptance of the processed fruit all along the storage period (Figure 1.4), so indicating that the ripening stage of the raw fruit is a key point in the production of high-quality frozen kiwifruit slices.

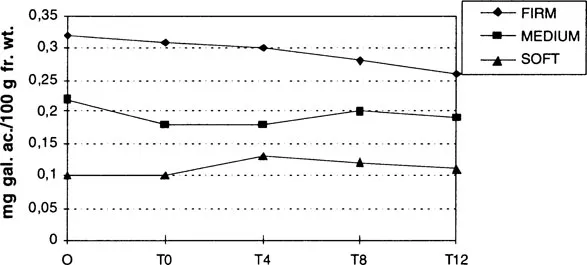

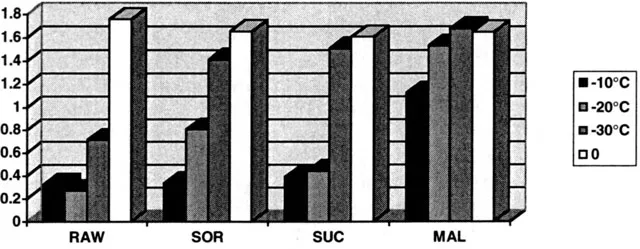

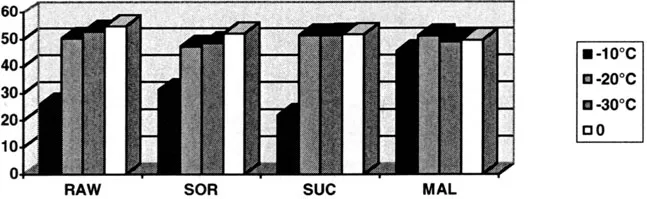

The second step in the combined process optimization was to evaluate the influence of the osmotic solution on the stability of chlorophyll pigments and ascorbic acid content of osmodehydrofrozen kiwifruit slices during frozen storage. According to the kinetic interpretation based on the glass transition concept, chemical and physical stability is related to the viscosity and molecular mobility of the unfrozen phase, which, in turn, depends on the glass transition temperature (Levine and Slade, 1988; Roos, 1992). So it has been hypothesized that the cryostabilization of frozen foods depends on the ability to store the food at temperatures less than its glass transition (Tg) or the ability to modify the food formulation to increase glass transition temperatures above normal storage temperature (Slade and Levine, 1991). Kiwifruit slices 10 mm thick were osmodehydrated in a 60% solution of sorbitol, sucrose, and maltose for 4 h, and then were frozen and stored at –10°C, –20°C, and –30°C for 9 months. The osmotic pretreatment modified the percent distribution of the sugars and thus the glass transition temperature of the fruits (Torreggiani et al., 1994). There was a correlation between the storage temperature and chlorophyll retention: the lower the temperature the higher the retention (Figure 1.5). At the same storage temperature, kiwifruit pretreated in maltose and thus having the highest Tg values showed the highest chlorophyll retention. Ascorbic acid content was stable at –20°C and –30°C, whereas there was a significative decrease at –10°C (Figure 1.6). At –10°C the ascorbic acid content showed the highest retention in the kiwifruit pretreated in maltose.

Figure 1.2 Texture values of kiwifruit slices after freezing (T0) and after 4 (T4), 8 (T8), and 12 (T12) months of storage at −20°C (Torreggiani et al., 1998b).

Figure 1.3 Pectin fraction R of kiwifruit slices after freezing (T0) and 4 (T4), 8 (T8), and 12 (T12) months of storage (Torreggiani et al., 1998b).

Figure 1.4 Texture and flavor acceptance of osmodehydrofrozen kiwifruit (Torreggiani et al., 1998b).

Figure 1.5 Chlorophyll content (mg/100 g fr. wt.) of kiwifruit slices, not pretreated (raw) and pretreated in sorbitol (SOR), sucrose (SUC), and maltose (MAL), after 9 months of frozen storage; 0 = content before freezing.

In the case of both chlorophyll and ascorbic acid content, the glass transition theory holds. Increasing the glass transition temperature through an osmotic step could increase the fruit stability during frozen storage. These data were confirmed by the results obtained by studying anthocyanin stability in osmodehydrofrozen strawberry halves (Fomi et al., 1997a) and color and vitamin C retention in osmodehydrofrozen apricot cubes (Fomi et al., 1997b). The protective effect of sorbitol observed both in osmodehydrated strawberry halves and apricot cubes could not be explained through the glass transition theory. Further research is needed to define all the different factors such as pH, viscosity, water content, and specific properties and characteristics of this sugar-alcohol, influencing pigment degradation.

The second goal of the research was to obtain high-quality, low-moisture kiwifruit products. Besides studying the dehydration methods (osmotic dehydration, air dehydration, and their combination), the dehydration levels (20, 30, 40, 50, and 60% weight loss) and their influence on color of the end products were also studied. Up to 40% weight loss osmodehydration and its combination with air dehydration did not significantly modify the kiwifruit color, whereas air drying caused a significant yellowing (Figure 1.7). The results show that 40% weight loss is the limit for kiwifruit pretreatments if high-quality products are required.

Figure 1.6 Ascorbic acid content (mg/100 g fr. wt.) of kiwifruit slices, not pretreated (raw) and pretreated in sorbitol (SOR), sucrose (SUC), and maltose (MAL), after 9 months of frozen storage; 0 = content before freezing.

By referring to this research on kiwifruit, it is easy to understand that despite the large number of theoretical and experimental studies, combined processes are still hard to find in the food industry. The wide range of possibilities regarding raw material characteristics, product characteristics, process parameters, and flow sheets make it very difficult for these processes to be applied. Bec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Preface

- Preface

- Acknowledgement

- List of Contributors

- Part I: Osmotic Processes in Fruit and Vegetables at Atmospheric Pressure

- Part II: Vacuum Impregnation and Osmotic Processes in Fruit and Vegetables

- Part III: Salting Processes at Atmospheric Pressure

- Part IV: Vacuum Salting Processes

- Part V: Vacuum Impregnation, Osmotic Treatments and Microwave Combined Processes

- Index