![]()

Part I

Sensors for Biological Applications

![]()

1 Advanced Sensing and Communication in Biological World

Abhisek Ukil

CONTENTS

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Bats: Echolocation

1.2.1 Introduction

1.2.2 Echolocation

1.2.3 Neurobiology and Physics of Echolocation

1.2.4 Utilization of Echolocating Capability

1.2.5 Engineering Adaptation

1.3 Insects: Acoustical Defense

1.3.1 Introduction

1.3.2 Aposematism

1.3.3 Signal Jamming

1.3.4 Insect Auditory Mechanism

1.3.5 Engineering Adaptation

1.4 Snake: Infrared Thermography

1.4.1 Introduction

1.4.2 Anatomical Structure

1.4.3 IR Detection Principle

1.4.4 Neurological Interpretation

1.4.5 Engineering Adaptations

1.5 Honeybee: Waggle Dance Communication

1.5.1 Introduction

1.5.2 Waggle Dance Pattern

1.5.3 Information Encoding in Waggle Dance

1.5.4 Controversy around Waggle Dance

1.5.5 Other Information in Waggle Dance

1.5.6 Engineering Adaptations

1.6 Dolphin, Whale: Sonar

1.6.1 Introduction

1.6.2 Biology, Neurobiology of Sound Production

1.6.3 Utilization: Echolocation

1.6.4 Utilization: Social Living

1.6.5 Utilization: Cultural Aspect and Emotions

1.6.6 Utilization: Whale Song

1.6.7 Utilization: Language

1.6.8 Utilization: Others

1.6.9 Influence of Noise

1.6.10 Engineering Adaptations

1.7 Others

1.7.1 Swiftlets: Echolocation

1.7.2 Fish: Electrolocation

1.7.3 Shrimp: Light Polarization

1.7.4 Marine Lives: Bioluminescence

1.7.5 Insect Katydid: Acoustic Mimicry

1.7.6 Mosquitoes: Sexual Recognition

1.7.7 Wasps: Finding Hidden Insects

1.7.8 Beetles: Gas Sensing

1.7.9 Cockroaches: Climbing Obstacles

1.7.10 Salamander: Limb Regrowing

1.7.11 Ants: Pheromone Communication

1.7.12 Paddlefish: Stochastic Resonance

1.7.13 Dragonfly: Aerodynamics

References

1.1 Introduction

The animal kingdom is vast and varied. The entire animal kingdom, ranging from the smallest insects to the biggest animals, relies on various sensory systems to interact with nature and live. The types of biological sensors found in nature exhibit enormous variation, like advanced sonar, infrared (IR) thermal sensors, advanced gas sensors, image sensor, vibration detector, chemical sensor, and so forth. Besides having advanced sensory systems, many creatures possess extraordinary communication capability to facilitate proper utilization of the sensory signals and transmit the important information to other fellow creatures. The sensors, associated signal processing, communication, sensor fusion often surpass the state-of-the-art manmade engineering systems. This chapter would provide an explorative study of the different biological sensory systems with the associated signal processing and the possible engineering adaptation of the relevant systems. However, this cannot in anyway be an encyclopedia of the vast amount of advanced sensory science abundant in nature. Some of the best studied creatures and their sensory mechanisms are described in the following sections.

The remainder of the chapter is organized as follows: In Section 1.2, echolocation capabilities of bats are discussed. Section 1.3 presents the amazing acoustical defense mechanisms of nocturnal insects, against the attacks of the bats. IR thermography in certain type of snakes is discussed in Section 1.4. This is followed by a discussion on the waggle dance communication of the honeybees, a Nobel prize winning discovery, in Section 1.5. Advanced sonar capabilities of the dolphins and the whales are discussed in Section 1.6. Finally, Section 1.7 presents brief discussions on sensory systems of several other species, including electrolocation by fish, polarized light sensing by shrimps, bioluminescence in marine lives, acoustic mimicry in insects, advanced gas sensing in beetles, flexible mechanical structures of cockroaches, chemical sensing and communication in ants, etc.

1.2 Bats: Echolocation

1.2.1 Introduction

Bats are one of the oldest mammals, the oldest known bat fossil is approximately 52 million year old. Over centuries, people had had curiosities for bats. They fly like birds, bite like beasts, hide by day, and see in the dark. In the folklores of different cultures, we can find instances of bats, for example, in the Greek storyteller Aesop, in the Latin culture, some Nigerian tribes and the North American Cherokee Indians, Chinese, Buddhists, Mayan, etc. In modern days, we also see big influence of bats on good (e.g., Batman) and bad (e.g., vampire) symbolizations.

Bats are the only mammal that can fly and has bidirectional arteries [1]. The forelimbs of all bats are developed as wings; that is why bats have scientific classification order as “Chiroptera” “cheir” (hand), and “pteron” (wing). There are about 1100 species of bats worldwide. About 70% of bats are insectivorous; most of the rest are frugivorous, with a few species being carnivorous [2]. Bats range in size from Kitti’s hog-nosed bat measuring 29–33 mm (1.14–1.30 in.) in length and 2 g (0.07 oz) in mass [4] to the giant golden-crowned flying-fox, which has a wing span of 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in.) and weighs approximately 1.2 kg (3 lb). Bats are classified in many different ways; most prominently they are classified as “megabats” and “microbats” [3]. Main characteristics of these two classes are mentioned as follows:

Megabats:

Microbats:

Usually smaller in size

Insectivores or carnivores

Practically no vision

Advanced auditory system: using echolocation to move and hunt [4,5]

Different ear and cochlea structure [6]

From the aforesaid classifications, it can be noticed that microbats employ an interesting mechanism called “echolocation” [7,8] to forge and hunt in almost darkness. It is to be noted that they have usually very poor vision; therefore, they rely on their auditory sensors to navigate.

Lazzaro Spallanzani made first experiments on bats’ navigation and location methods in 1793. He noted that bats were fully able to navigate with their eyes covered and in total darkness. Spallanzani conducted series of experiments in 1799, eventually concluding that even though bats did not use their eyes, covering or damaging their ears would prove invariably fatal to them, as they would stumble on any and all obstacles and be unable to catch any prey.

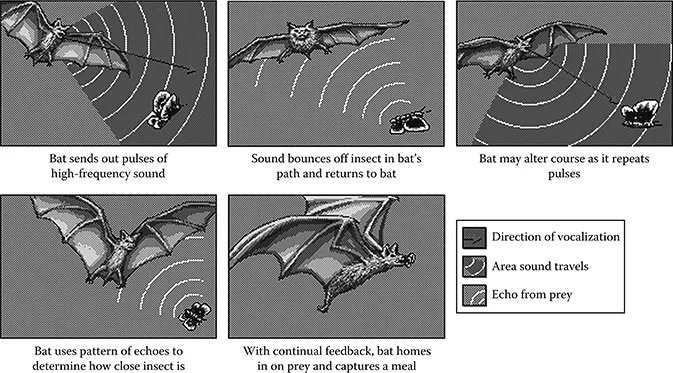

1.2.2 Echolocation

Bat echolocation is a perceptual system where ultrasonic sounds are emitted specifically to produce echoes. By comparing the outgoing pulse with the returning echoes, the brain and the auditory nervous system can produce detailed images of the bat’s surroundings. This allows bats to detect, localize, and even classify their prey in complete darkness [8,9]. Bats emit echolocation sounds in pulses. The pulses vary in properties depending on the species and can be correlated with different hunting strategies and mechanisms of information processing [1], as shown in Figure 1.1. Bat uses timing, frequency content, duration, and intensity of the echo pulses in an adaptive way to catch the prey that is also moving.

FIGURE 1.1 Echolocation mechanism of bats to catch prey in real time using ultrasound signals in an adaptive manner.

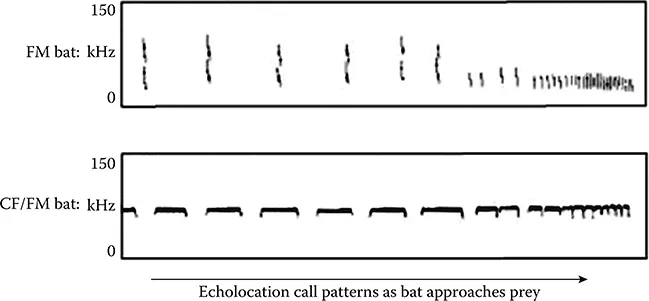

Echolocating bats use frequency modulated (FM) or constant frequency (CF) signals for orientation and foraging. Many types of bats use FM pulses with downward sound that sweeps through about an octave. Others use CF and FM signal combinations. The CF component occurs around 27 kHz, with a duration of about 20–200 ms. The FM component sweeps down from 24 to 12 kHz, with a prominent second harmonic from 40 to 22 kHz [10]. Evolutionary developments of the FM or CF/FM type echolocation capability in bats have been motivated by several factors like nature of structural anatomy [11], habitat [12], foraging behavior [13], etc.

The CF and FM signals serve different purposes. For example, the narrowband CF signals are used to localize targets and to determine target velocity and direction [10]. In comparison, FM signals, with broader bandwidth, are used to form a multidimensional acoustic image to identify targets [10].

Bats that use mixed signal forms usually hunt in cluttered environments where prey detection is harder for bats that use only FM signals. The mixed signals are of three basic types: FM/short-CF, short-CF/FM, and long-CF/FM sounds. Even though most of the species use only one type of sound [10]. The difference in foraging behaviors of the FM bat and CF/FM bat is shown in Figure 1.2.

Main characteristics of the CF/FM and FM type bats are mentioned as follows:

CF/FM bat

Uses mixed signal with longer CF part with short narrowband FM part

Lives mostly at dense places, caves, etc.

Has Doppler shift compensation (DSC) to compensate own wing flattering and increase resolution accounting for insects’ wing flattering [8]

Does not have advanced delay time processing

Has higher sensitivity and frequency selectivity, adaptive motion control [13]

FM bat

Uses shorter duration broadband signals

Lives mostly in open forest

Has no DSC

Can differentiate delay time less than 60 μs [8]

Has better target localization

FIGURE 1.2 Different echolocating calls: FM and CF/FM bats.

Evolutionary developments of echolocating capabilities in different bat species are described in Ref. [11]. For example, Cynopterus brachyotis shows no echolocation, Rousettus aegyptiacus shows brief, broadband tongue clicks, Lasiurus borealis uses narrowband, fundamental dominated pulses, narrowband multiharmonic pulses are used by Rhinopoma hardwickii and Taphozous melanopogon, short broadband multiharmonics are used by Megaderma lyra and Mystacina tuberculata, and long broadband multiharmonics are used by Myzopoda auritam, etc. [11].

1.2.3 Neurobiology and Physics of Echolocation

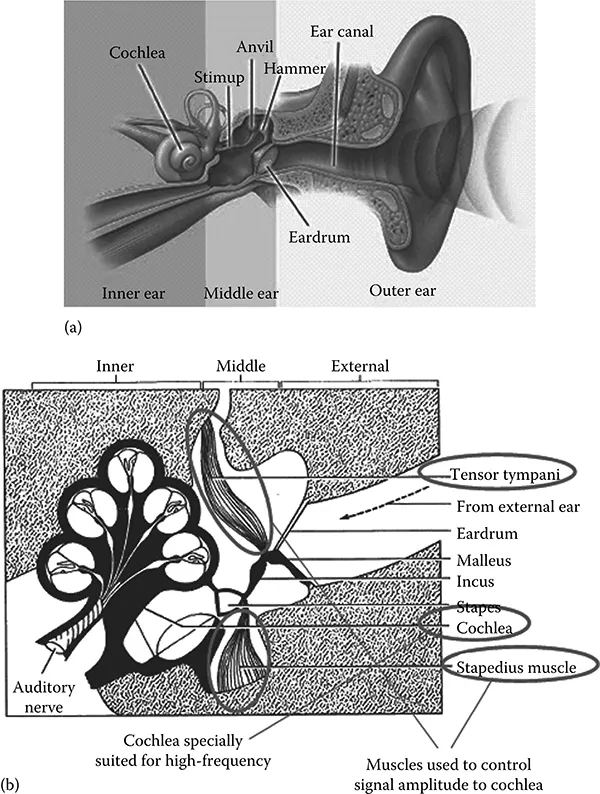

FIGURE 1.3 Anatomical structures of (a) human ear and (b) bat ear.

The anatomical structures of the bat ear, vis-á-vis human ear, are shown in Figure 1.3. In general, for echolocation, bats have bigger pinna [6]. They also have specialized muscles...