![]()

1 Introduction

Lawrence Sáez and Gurharpal Singh

Introduction

The 2009 general election in India revealed that, contrary to conventional wisdom, a governing coalition can complete a full term of office and be re-elected. This landmark development, after almost 20 years of coalition governments, suggests that India’s transition to an era of minority governing coalitions has reached a degree of systemic stability. The concept of systemic stability under conditions of coalition governance in democratic parliamentary systems has an extensive pedigree in political science. For instance, William Riker’s seminal work (Riker 1962) on the theory of coalitions has generated a rich tradition of analysis into the dynamics behind cabinet formation and government durability that has subsequently been extended by others (see Taylor and Herman 1971; Dodd 1974; Brass 1977; Mitra 1980; Lijphart 1984). Game-theoretic and institutionalist approaches to the subject of systemic stability also share a common perspective that the size and the policy distance between coalition actors have specific expected outcomes in terms of cabinet size and government durability. Moreover, analytical perspectives that focus on ideology (Strom 1985, 1988) predict that ideological cohesiveness and the potential conflict levels among coalition partners can affect the expected duration of a coalition government.

In the literature on the transformation of India’s political system from a dominant one-party system to coalition politics, a great deal of attention is paid to the institutional mechanisms in the functioning of party systems. Since 1989, India has had six minority governing coalitions, some of them short-lived. Scholarly analyses of these governments has focused on the features of minority coalition governments at the national level (Manor 1994; Sridharan 2003) or changes in the party system at the sub-national level (Sáez 2002; Heath 2005; Wilkinson 2005). Other authors have also attempted to evaluate the impact of coalition politics on public policy formulation against the backdrop of the rise of Hindu nationalism, (Adeney and Sáez 2005), increasing corruption (Singh 2005) and minority, gender and affirmative action rights (Mitra 2005; Rao 2005).

Ideological difference between the parties, as we shall see below, and in the papers presented in this volume, are significant in determining the policies pursued, but in India these cannot be easily framed or understood within the existing political science literature. For example, Downsian models of democracy (Adams et al. 2004; Adams and Somer-Topcu 2009; Ezrow 2005, 2008) postulate that in plurality elections there should be a party convergence towards the views of the median voter. While this is no doubt the case in that successful winning coalitions in the last 20 years are those that have sought to appeal to middle ground – the traditional center occupied by Congress – the implicit assumption about rational utility-maximizing voters in Downsian models can be difficult to apply in India because of the different arenas under which party competition takes place.

Arenas of Political Competition

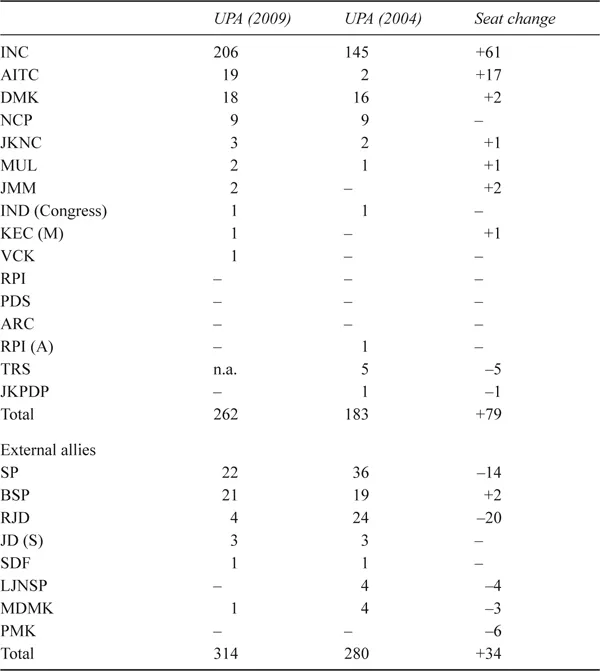

A minority coalition government in India normally faces two challenges. At a national level it must stave off potential threats from the non-governing opposition coalition. More importantly, it must engage with the components of the coalition itself. Such coalitions can be unstable if there is a high degree of internal fractionalization; that is, division of support among the constituent parties. For this reason, minority governing coalitions must be able to maintain stability by ensuring a minimum number of parliamentary seats to secure a simple majority. In India’s case this means securing more than 272 parliamentary seats. As Table 1.1 shows, in 2004 the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) obtained 248 seats and in addition had the support from four parties (the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), the Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) and the Lok Jan Shakti Party (LJNSP)). In 2009, the UPA coalition increased its seat share to 262 parliamentary seats (nearly 96.3 per cent of the seats needed to obtain a simple majority). Its external allies in the 2004 general election suffered a substantial decline in total seats (a net loss of 45 seats). However, with the enhanced position of the Indian National Congress (INC, henceforth Congress/Congress Party), the UPA coalition was in a firmer parliamentary position in 2009.

Nonetheless, as Duverger (1951: 324) has noted, alliances between parties ‘can vary greatly in form and degree. Some are ephemeral and unorganized … others are lasting and are strongly organized, so that sometimes they are like super-parties.’ The UPA’s coalition governments in 2004 and 2009 have features of growing organization and strength, but it is worth remembering that India’s minority governing coalitions in 2004 and 2009 necessitated more than 11 parties to secure a simple parliamentary majority.

Table 1.1 UPA performances in 2009 and 2004

Notes

1 UPA coalition allies in 2004 included the INC, TRS, RJD, LJNSP, NCP, JMM, JKPDP, MUL, KEC (M), JD (S), RPI, RPI (A), DMK, MDMK, PMK, PDS, ARC and IND (Congress). Many of these parties were not UPA allies in 2009.

2 Political party acronyms correspond to those used by the Electoral Commission of India.

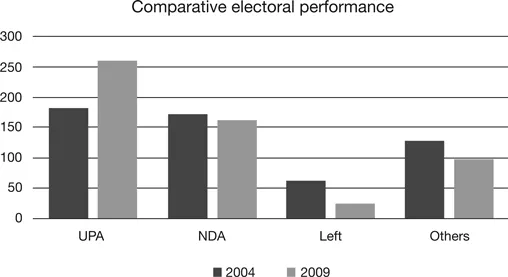

Figure 1.1 shows that there has been a significant shift in parliamentary strength of the core group of UPA coalition allies, relative to the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), from 2004 to the 2009 general election. Figure 1.1 also shows that the parliamentary strength of the leftist parties has diminished considerably between 2004 and 2009.

Figures represent number of parliamentary seats obtained by each parliamentary group. Figures for the UPA and the NDA exclude external coalition supporters.

Figure 1.1 Comparative electoral performance of the principal parliamentary groupings (2004 and 2009)

India’s federal system represents a secondary arena of political competition. Individual national parties, like the Congress or the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), must also compete at a provincial level. Although the national electoral cycle is five years, Indian political parties must contest a plethora of state assembly elections every year. This ongoing system of sub-national electoral competition forces the main national political parties to pursue national policies that will not alienate its allies in regional electoral contests.

During the last two national electoral cycles (2004 and 2009), the INC and the BJP have been competitive in about half of India’s state assemblies. For instance, Table 1.2 shows the comparative level of strength of the INC and the BJP in 14 state assemblies in India in 2004 and 2009.

Table 1.2 List of state assemblies controlled by either the INC or the BJP in 2004 and 2009

|

State assembly | 2004 | 2009 |

|

Andhra Pradesh | INC | INC |

Assam | INC | INC |

Chhattisgarh | BJP | BJP |

Goa | BJP | INC |

Gujarat | BJP | BJP |

Himachal Pradesh | INC | BJP |

Jharkhand* | BJP | JMM |

Karnataka | INC | BJP |

Kerala | INC | CPM |

Madhya Pradesh | BJP | BJP |

Maharashtra | INC | INC |

Manipur | INC | INC |

Meghalaya | INC | INC |

Mizoram | MNF | INC |

Rajasthan | BJP | INC |

Uttarakhand | INC | BJP |

|

Note

* Jharkhand was under President’s Rule from 19 January 2009 until 29 December 2009. The list does not include union territories.

As Table 1.2 shows, between 2004 and 2009, there has been some alternation in six of these states. Three states (Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, and Uttarakhand) switched from the INC in 2004 to the BJP in 2009. In turn, two states (Goa and Rajasthan) switched from the BJP to the INC during the same time period. One state (Jharkhand) switched from the BJP to a regional party (the JMM) from 2004 to 2009, one state (Mizoram) switched from a regional party (the MNF) to the INC. The state of Kerala switched from the INC in 2004 to the CPM in 2009. Outside these 16 states, the level of penetration by the two largest national parties in India’s state legislatures is severely constrained.

To complicate matters, some political parties (e.g. DMK, Telugu Desam Party (TDP), CPM) are essentially provincial parties that often compete against and form alliances with the two main national parties (Congress and BJP). Since the de-linking of national and state elections in 1967, political competition in the states has produced a variety of party systems ranging from the dominant to multiparty systems (Rudolph and Rudolph 1987; Nikolenyi 1998; Sáez 2002). In some ways, though, the most significant change has come about as result of the rise of dalit parties in north India (SP, RJD and the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP)) that have effectively eroded Congress party support, especially in its northern heartland (Chandra 1999, 2000; Jaffrelot 2000). For instance, the Congress party has not governed the state of Bihar since 1990 and Uttar Pradesh since 1998. In these conditions, national coalition building requires not only that ideological and policy differences are accommodated, but it also necessitates that the coalition building and maintenance process is able to reconcile the demands of these regional parties, which often can be idiosyncratic, designed to outbid their main political rival in the state (e.g. DMK) or, still, determined by their pragmatic relationship with either the Congress or the BJP.

The UPA as a Political Phenomenon

To date there has been no serious analysis of the UPA in power. The literature on the Congress party, both from an overarching historical perspective as well as its role in Indian politics, is quite extensive (Franda 1962; Kothari 1964, 1974; Morris-Jones 1967; Kochanek 1969; Mendelsohn 1978; Rudolph and Rudolph 1980; Chand 1985; Gehlot 1991). Some scholars, however, have tried to develop our understanding of the changing role of the Congress party within an era of coalition governments in India (Vanderbok 1990; Singh 1992; Pai 1996; Candland 1997). It is only in recent years that there has been a renewed interest in the Congress party as a leading force in a governing coalition. For example, Johari (2006) provides a useful example of the analysis of the party’s development, including a chapter on the UPA. More narrowly, Bijukumar (2006) aims to evaluate Congress’s economic policies, but only offers a cursory treatment of the subject. Although useful in their own right, these works do not really offer a comprehensive assessment of the UPA’s performance across a broad range of policies. Nor for that matter do they evaluate the performance of the UPA coalition once it was in power.

The issue of the challenges faced by minority governing coalitions has sparked an intense debate among Indian politics specialists. For instance, Chakravarti (2006) offers a sound analysis of the historical structure of national governing coalitions in India. However, the book takes an aggregate look at the phenomenon of coalition politics over time (focusing on three co...