![]()

Chapter 1:

Action & Coordination

![]()

Nonlinear Attractor Dynamics and Symmetry Breaking in Prism Adaptation and Re-adaptation

Julia J. C. Blau1, Damian G. Stephen1, Till D. Frank1, M.T. Turvey1, 2, & Claudia Carello1

1 Center for the Ecological Study of Perception and Action, University of Connecticut, USA, 2Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, CT USA.

The typical prism adaptation paradigm consists of three phases (Fig. 1, panel 1). In the baseline phase, participants throw to a target to establish their average natural deviation from the target. During adaptation, participants wear prism goggles that shift their gaze. The disturbed vision results in an initial systematic deviation from the target, and exponential error decay as the participant adapts to the perturbed perception-action system. The prism goggles are removed for the third phase, re-adaptation. At this point, the perception-action system is still adapted to the perturbation; which results in systematic error in the opposite direction of the original error, known as the aftereffect. This aftereffect is eliminated exponentially over the rest of the phase.

Prism Adaptation—An Extended Case. An extension of the paradigm reveals that when experimental conditions (presence of a wrist weight; Fernandez-Ruiz et al., 2000) differ during adaptation and re-adaptation phases (symmetry breaking), then re-adaptation is only partial. Performance error (aftereffect) does decay; however, when experimental conditions are re-established (symmetry regained), performance error returns (latent aftereffect) and another re-adaptation process occurs.

Error Decay and the Dynamic Systems Approach. Adaptation, the error decay of the aftereffect, and the latent aftereffect all exhibit gradual, exponential error decay, rather than one-trial learning. One explanation of this phenomenon is that the system is only calibrated for fine-tuning, with a maximum step per throw (Fernandez-Ruiz & Diaz, 2006). However, a dynamical systems approach might offer new insights. Dynamic systems theory is a powerful approach to examining perception-action systems (Beek et al., 1995; Kelso, 1995). Learning approached from this perspective has been associated with the emergence of attractors and self-organized states (Schöner & Kelso, 1995). We propose a dynamic model for prism adaptation.

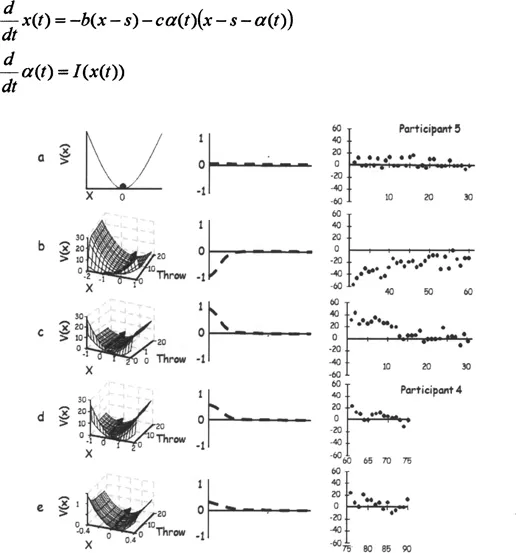

The Model. Evolution of distance-to-target, x(t), depends on the intrinsic attractor, VO, and the adaptation attractor, VA. The intrinsic attractor is invariant; the adaptation attractor emerges during an adaptation process and vanishes in the course of a re-adaptation process. The evolution of x(t) is defined by:

where V(x, t) is the total potential VO (x) + VA(x, t). VO and VA can be modelled explicitly and predictions can be derived (Fig. 1, first two columns) by solving the model equation numerically and analytically (Frank, Blau, & Turvey, 2009). For an adaptation process we studied a model equation of the form:

Figure 1. Explicit models (first column), predictions (second column) and examples of corresponding results (third column) in the general (panels a-c) and extended (panels d and e) prism adaptation paradigm.

where s is the prismatic shift, and α is a time-dependent function of the adaptation potential VA (Fig. la, b). For the re-adaptation dynamics, s = 0 (Fig. 1c). For the extended prism paradigm, we add a constant term, δ, that accounts for the symmetry-breaking (Fig. 1d). For the secondary adaptation process δ = 0 (Fig. 1e). (See Frank, Blau, & Turvey, 2009, for a full explication of the model).

In this model, the symmetry-breaking term, δ, must be defined experimentally. Although mass has been suggested as a possibility, the mass manipulation of Fernandez-Ruiz et al. (2000) is conflated with rotational inertia. These variables are disentangled in our experiment by placing a given mass at one of two locations on the arm, thereby manipulating rotational inertia while keeping mass constant. This also offers us the opportunity to compare our model predictions to actual experimental data (Fig. 1).

Method

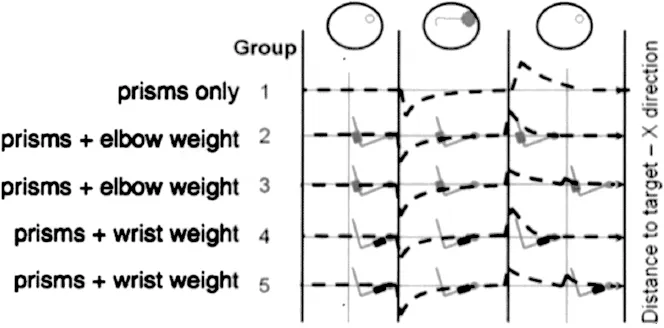

Forty undergraduates with normal or corrected-to-normal vision were assigned randomly to one of five groups defined by when, where, or whether prisms and weights were added or removed (Fig. 2). On each trial, a 108 g bean-bag was thrown to a target 2.5 m away. Prisms (30-diopter Fresnel lenses) shifted vision to the left. A 1.15 kg band attached at the elbow brought about a smaller change in rotational inertia than that same band attached at the wrist.

Figure 2. Vertical lines indicate when prisms and/or weights were added or removed. Results are symbolized by the dashed line. By convention, deviations below the horizontal line are to the left.

Results and Discussion

Model Fit. In all cases, the data fit the model predictions (Fig. 1, last column), suggesting that a dynamical systems model can account for gradual learning behaviour such as prism adaptation. The model was also able to account for the symmetry breaking (Fig. 1d, e).

Symmetry Breaking Term. The first aftereffect was smaller and the latent aftereffect was greater in groups 3 and 5 than in groups 2 and 4, F(1, 30) = 12.82, p < .002, confirming the existence of the latent aftereffect under conditions of symmetry breaking (Fig. 2). In Groups 1, 3, and 5, the first aftereffect declined and the latent aftereffect increased across groups, F(2, 21) = 13.94, p < .0001, suggesting that rotational inertia, not mass, is the variable responsible for the symmetry breaking. Further research should uncover more variables that cause such a break in an effort to discover the underlying cause (see Blau, Stephen, Carello, & Turvey, under review, for a full discussion).

General Discussion. Prism adaptation does not exhibit one-trial learning. Prism adaptation is a dynamic process that can be described in terms of an evolution equation. Adaptation processes involve the emergence of behavioural patterns. Our modelling approach reveals that these patterns emerge in a nonlinear system. In short, our analysis suggests that adaptation requires nonlinearities. The context-dependency of prism adaptation can be understood as breaking the symmetry of conditions during adaptation and re-adaptation. Taking a dynamic systems perspective, symmetry-breaking reveals itself as an additive force. By fitting the proposed model to experimental data, meaningful parameters can be derived. Since the study of prism adaptation has clinical relevance (Brooks et al., 2007), these parameters could be used for diagnostic purposes.

References

Beek, P. J., Peper, C. E., & Stegeman, D. F. (1995). Dynamical models of movement coordination. Human Movement Sciences, 14, 573–608.

Blau, J. J. C., Stephen, D. G., Carello, C., & Turvey, M. T. (under review). Prism adaptation of underhand throwing: Rotational inertia and the primary and latent aftereffects.

Brooks, R. L., Nicholson, R. I., & Fawcett, A. J. (2007). Prisms throw light on developmental disorders. Neurophysiologica, 45, 1921–1930.

Fernández-Ruiz, J., & Díaz, R. (2006). Prism adaptation and aftereffect: Specifying the properties of a procedural memory system. Learning & Memory, 7, 193–198.

Fernández-Ruiz, J., Hall-Haro, C., Díaz, R., Mischner, J., Vergara, P., & Lopez-Garcia, J. C. (2000) Learning motor synergies makes use of information on muscular load. Learning & Memory, 7, 193–198.

Frank, T. D., Blau, J. J. C., & Turvey, M. T. (2009). Ninlinear attractor dynamics in the fundamental and extended prism adaptation paradigm. Physics Letters A, 373(11), 1022–1030.

Kelso, J. A. S. (1995) Dynamic patterns. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Schöner, G. S. & Kelso, J. A. S. (1988). A synergetic theory of environmentally-specified and learned patterns of movement coordination: I. Relative phase dynamics. Biological Cybernetics, 58, 71–80.

Acknowledgments. This research was supported by National Science Foundation grant SBR 04-23036.

![]()

Functional Tuning of Action to Task Constraints in Tool-Use: The Case of Stone Knapping

Blandine Bril, Robert Rein, & Tetsushi Nonaka

École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, France

Tool use appears as a privileged entry to understand goal directed actions, the organism being not simply directed toward the goal, but rather directed by the goal (Shaw, 1987). The aim of the current study is to characterize the expertise in the earliest known instance of human tool-use, stone knapping, from the perspective where the emphasis is on the goal while the movement is viewed as driven by task constraints.

In stone knapping, one stone (hammer) is used to strike another (core) to remove a sharp-edged piece (flake) according to the fracture mechanism called conchoidal fracture. Counter intuitively, in conchoidal fracture, it has been demonstrated that the force of the blow does not play a major role in determining the dimension of the detached flake (Dibble & Pelcin, 1995). It does, however, play a critical role in determining whether or not a flake can be produced in the first place. Therefore, kinetic energy of the hammer at impact is one of the essential task constraints for flake production, and we hypothesized that if actions are controlled in a functionally specific manner, knappers would maintain the kinetic energy of the hammer at impact invariant irrespective of the mass of hammers used. In other words, the achievement of the goal, the removal of a flake, is driven in such a way to meet the constraints of the task, that is, to produce the required kinetic energy of the hammer at impact of the strike.

Method

Nine participants with different knapping experience (two experts, three intermediates and four novices) participated in the experiment. Two hammers with different mass (heavy: 400g, light: 250g) were used. Flint weighing between 2-3 kg was used as cores. Striking movements were recorded using an Ascension miniBIRD© magnetic marker system set at a recording frequency of 100Hz. One sensor was attached to the backside of the hand. Each participant produced twenty flakes with each hammer. The trajectory length of the hammer was calculated based on the trajectory of the hand sensor in 3D space from the maximum vertical height to the point of impact. The kinetic energy was calculated using the formula Ekin = ½ m v2 (v = resultant velocity). A linear mixed-model analysis incorporating hammer weight and skill level in the fixed-effects structure and subject as a random effect was used for statistical analysis, and Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests were used for multiple comparisons.

Results and Discussion

590 strikes contributed to the analysis. Success rate of flaking per group was 84% for experts, 55% for intermediates, and 49% for novices.

Hammer trajectory length. Statistical analysis indicated a significant main effect for hammer weight, F(1, 577) = 79.1, ...