1.1 Introduction

Electricity provides consumers with the ability to realize numerous conveniences in their everyday lives. One does not buy electricity as an end product. One buys electricity as an input which is then utilized to produce consumable goods and services or to enjoy domestic comforts. Compared to most other everyday products, electricity is elusive because it does not possess a physical form. Electricity is energy, and it is readily available to the consumer in a most unique way.

Flip a switch and an electric lamp is immediately illuminated. The “order” is simultaneously placed by the consumer and filled by the supplier. Electricity arrives on a just-in-time delivery basis. No practical applications of mass electricity storage exist today; therefore, electricity must be produced and transmitted to the point of use upon demand. Electricity travels fast at about 186,000 miles per hour. The continuous, high speed transportation of this energy requires a reliable power production and delivery system to ensure that the demands of all consumers are met continuously.

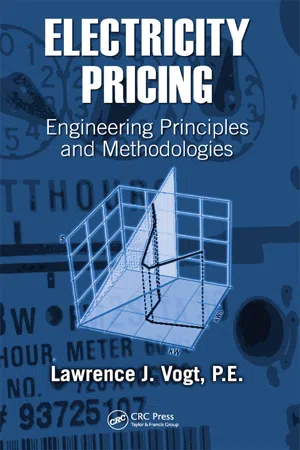

A massive infrastructure of electric utility systems has been developed. Electricity is generated at central stations and then transmitted to consumers via a complex network of wires which are operated at a variety of voltages. The basic organization of the electrical power system is shown in Figure 1.1. Three major functions are identified: production, transmission, and distribution.

The production plants are facilities where other forms of energy are converted into electrical energy by means of a generator. The relatively low voltage output of the generator is transformed to higher voltages in order to effectively transmit power to consumers, many of whom are located far away from the plants. The transmission system operates at high voltage levels in order to move large amounts of power over long distances to load centers (i.e., towns and regions within large cities). At the load centers, the high level voltages are transformed into medium level voltages for the distribution or routing of power within different locales. At various service points along the distribution system, the medium voltages are transformed to low voltages at which many electrical devices, or loads, operate.

As indicated in Figure 1.1, customers may take electric service at any functional level of the power system depending on their specific needs. In general, large commercial and industrial customers receive service at higher voltages than smaller customers. Residential customers are predominantly served at the lowest voltage level.

Figure 1.1 Functional organization of the electric power system. The major functions represent different levels of operating voltage.

In addition to the principal functions of producing and delivering energy, electric service includes a number of attendant services. The power system provides energy to customers having rather dynamic requirements. The energy needs of customers vary significantly in correspondence to the diverse operations of a variety of loads composed of electrical equipment and appliances. Taken together, the load requirements imposed on the power system fluctuate significantly from moment to moment. The power system is designed and operated to provide the capacity necessary to adequately serve the load in this fashion. Thus, the ongoing process of balancing generation with dynamic loads represents one example of an ancillary service which is provided as a responsibility of the system operators. Another example of an ancillary service is reactive power, which is required for system voltage control and to meet the power factor needs of customers.

Other nonelectric attendant services are also included with the rendering of electric service. Metering, billing, and customer accounting are functions which are necessary in order to properly invoice customers and maintain the records of customers’ usage and payment histories. Additional utility functions include customer service representatives and education programs which deal with such topics as electrical safety and energy usage and management methods.

Types of Customers

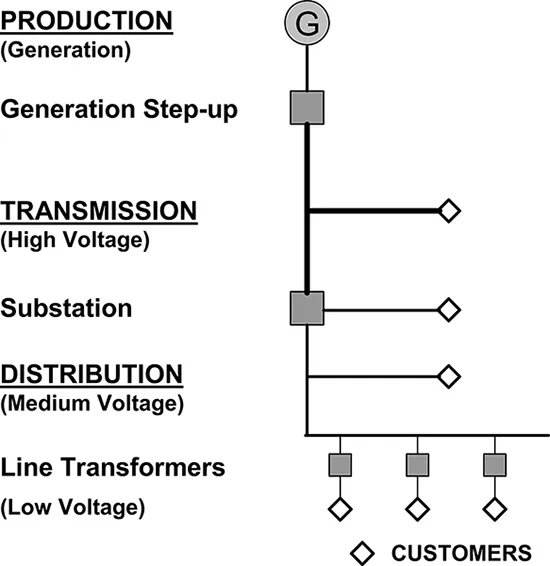

Electricity sales are generally categorized along the lines of customer classes. Figure 1.2 illustrates the customer segment groups which are typically used to delineate customers by class of service. A utility may provide service to both retail and wholesale customers. Customers in the retail sector are ultimate users of electricity. Lighting service customers are actually residential, commercial, public authority, and industrial types of customers. Each of these primary classes may separately purchase outdoor lighting service for safety and security reasons. Cities, towns, and communities require lighting service for illumination of streets, highways, and interchanges. Lighting service can consist of only electricity, or it can also include the actual fixtures, lamps, and the associated maintenance responsibility. Customers in the wholesale sector purchase electricity from a utility for resale to other entities or to their own ultimate customers.

Territorial or native customers represent a utility’s retail customers and its wholesale requirements customers, or municipals and cooperatives. Wholesale customers may be classified as taking either full requirements service or partial requirements service. Partial requirements customers have some generation resources which must be supplemented with wholesale electricity purchases in order to meet the needs of their ultimate customers. Traditionally, other wholesale customers consisted of adjacent, interconnected utilities that established interchange agreements for the basic purpose of economy and emergency purchases and to augment generation construction schedules. But with contemporary changes in the wholesale sector, a number of new buyers and sellers have appeared, including power marketers, brokers, and customer aggregators.

Figure 1.2 Classifications of utility customers. An example of an investor-owned utility’s customers. Retail service is provided to ultimate customers (end users). Wholesale service is provided to other utilities and service providers for resale purposes. Requirements service customers may own production facilities which meet a portion of their load.

Key Electricity Pricing Concepts

Pricing of electric service must take into account both the production and delivery of electrical energy as well as the attendant services required to adequately render service. While similar to other products and services in many respects, electricity possesses its own exceptional characteristics. As a result, the process of pricing electricity is both complex and unique.

To simply compute a single price per kilowatt-hour (kWh) to be applied to all kWh usage, regardless of customer type, would grossly ignore the distinct differences that exist in the ways in which customers utilize electricity. By carefully assessing these distinctions, a number of factors which justify price differentials can be recognized. For example, much of the power system is jointly shared by all customers. All customers share in the use of generation resources. Furthermore, all customers share in the use of the transmission system. But customers taking service at the transmission level do not utilize the utility’s distribution system. Transmission customers have their own transformation facilities and distribution systems; thus, the prices for customers served at a transmission voltage should not include any cost recovery for the utility’s distribution facilities. Meanwhile, customers served at primary and secondary voltage levels would share in the costs of the primary distribution system. This observation leads to the rationale for pricing which is differentiated by voltage level.

Temporal variations in the way in which electricity is utilized lead to another significant pricing differential. The power system experiences periods during which the combined loading of all of the customers is much higher than at other times. This on-peak period vs. off-peak period situation is quite prevalent throughout the industry in terms of both seasonal and daily variations. During peak loading conditions, such as a summer afternoon in climate zones when customers are using air conditioning extensively, a major portion of the power system’s capability is utilized. The system is designed and built to carry such loads adequately (since storage is not possible). As a result, when the load falls off at night, the system’s capability becomes underutilized. Simply stated, more costs must be incurred to serve peak period loads than to serve off-peak loads. This observation leads to the rationale for pricing which is differentiated by time.

A distinction in pricing can also be raised due to spatial variations of the system. Consider, for example, an area that is experiencing an accelerated level of growth compared to an adjacent area that has been “built out,” possibly for some time. Such a situation often occurs within the same city. The high growth area requires significant distribution system upgrades in addition to completely new facilities, including perhaps a new substation. In contrast, customers located in the older area continue to be served by fully operational distribution system facilities of an earlier vintage, which were constructed to serve the electric loads of the day. An inspection of the costs relative to these two areas would reveal a higher cost to serve customers located in the fast growing area.1 This observation leads to the rationale for pricing which is differentiated by location.

Another pricing distinction occurs relative to the configuration of local facilities. Obviously, customers with high peak loads require higher capacity service equipment than do smaller customers. But some customers (e.g., those with large motor loads) have a requirement for three-phase power while many other customers only need single-phase power. In comparison, three-phase service requires more conductors, transformers, and protective devices than single-phase service. Metering cost is also greater for three-phase service. Even at the same overall capacity requirement, three-phase service typically would be more expensive than single-phase service. This observation leads to the rationale for pricing which is differentiated by character of service.

A final observation relative to pricing distinctions can be recognized from the type of construction. Specifically, service provided from underground transmission and/or distribution facilities may require a greater investment than service provided from overhead facilities (except for higher density loads). On the other hand, underground facilities are less exposed to the types of physical hazards faced by overhead facilities; thus, underground distribution may offer an advantage with respect to reliability. In general, the overhead method of delivering electricity often represents the least-cost approach.

The common theme uncovered in each of the preceding discussion points is that, within an electric power system, certain situations often occur which lead to the existence of cost-of-service differentials between individual customers (even within the same customer segment) and between dissimilar groups of customers. Recognition of the more significant cost-of-service differentials through pricing structures is necessary to ensure reasonable equity between customers while balancing the inherent risks assumed by each of the parties. In short, costs should be more accurately attributed to those who require that those costs be incurred.

To adequately capture the cost-related attributes of electricity through pricing, while preserving equity among customers, three individual pricing components are recognized.

■ Customer Component - the costs associated with a customer’s connectivity to the power system2

■ Demand Component - the costs associated with a customer’s maximum load requirements

■ Energy Component - the costs associated with a customer’s requirements for a volume of electricity, i.e., kWh

These elementary pricing components represent unit prices or rates and are combined and modified in a variety of fashions to form the basic billing mechanism or rate structure. The form of rate structure is varied for different customer segments in order to reflect the cost distinctions of each of the groups. Typically, simplistic rate structures are utilized for small residential and commercial customers while more complex rate structures are used for large commercial and industrial customers. Taken together, the rate structures of all of the customer classes represent the nucleus of the electric tariff.

1.2 Objectives of the Electric Tariff

The tariff is a comprehensive document which contains all of the prices and contract features under which electric service is rendered.3 In addition to the basic rate structures for the various customer classes, a number of supplementary stipulations and clauses are required. These auxiliary provisions are needed to define such aspects as the qualifications for service, the character of service, and the term of service. Furthermore, a variety of additional billing clauses are needed to price specific service issues, such as power factor, which are not always addressed within the basic rate structure. To accomplish this objective, a rate schedule is established for each classification of service.

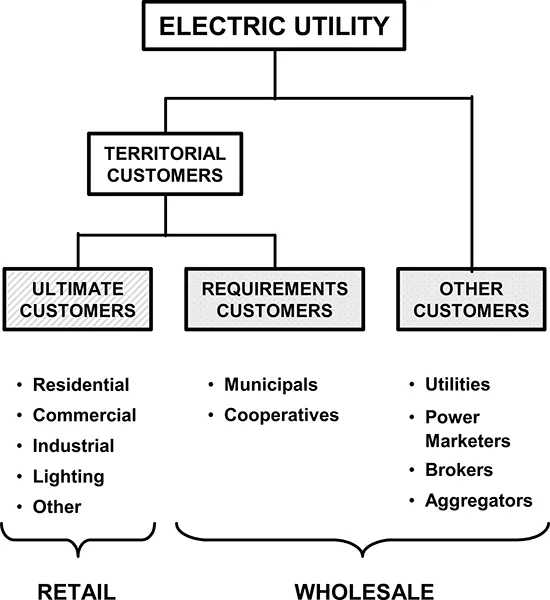

Rate schedules may be end-use specific, customer class specific, or general in nature. General service rate schedules apply across the commercial and industrial customer classes. Examples of common electric service rate schedule applications are shown in Figure 1.3.

In addition to the rate schedules, the tariff specifies the general terms and conditions for service which are rules and regulations that apply commonly to all classifications of customers. Some examples of such stipulations would be restrictions in the use of the service, billing and metering methods and requirements, and line extension policies.

The Stakeholders of Electricity Pricing

While many aspects of a utility and its operations are rather obscure to those outside of the business, the tariff receives a lot of attention from many bearings. The electric tariff has the objective of satisfying the interests of three principal stakeholder groups: customers, the utility, and jurisdictional regulators.

Historically, customers have been served exclusively by a local utility which typically operates in a specified franchise area. No other suppliers have been allowed to compete for customers within these restricted service territories. All new customers locating within a franchise area are required to take electrical service only from the incumbent utility. This utility-customer relationship is a classical example of a monopoly operation. Consequently, pricing of electrical services have fallen under the scrutiny of local and national governmental agencies which serve as utility regulators.

Figure 1.3 Examples of retail electric service rate schedule applications. Rate schedules may be customer class specific or general in nature. General service rates apply across two or more customer classes. Special rates may apply only to specific customer end-use applications.

Customers have come to view electricity as an essential public service. Like any other product or service, customers seek value from electricity and expect a price leve...