![]()

1 The Three L’s: Location, Location, Location

If you are a robot, you are blind, deaf, and do not know where you are. This is equally true if you are a robot moving around on Mars, as if you are a robot moving around in a building at night. In the field of mobile robotics, localization has been referred to as “the most fundamental problem to providing a mobile robot with autonomous capabilities” (Cox, 1991). Autonomous robots are built on mobile platforms, where a new degree of control flexibility is needed. As opposed to industrial robots, they move around in their environment, which is often highly unstructured and unpredictable. Slowly, various markets are emerging for this type of robotic system. Entertainment applications and different types of household or office assistances are the primary targets in this area of development. The Aibo dog from Sony and the Trilobite vacuum cleaner from Electrolux are early examples of this future industry.

Outdoor positioning, using global positioning systems (GPS) or techniques that measure the position of the user in a cellular network, have been well explored and standardized. But GPS does not work indoors and may not give you the accuracy you need to move around. You need some way to measure your position in the building, to make sure where you are and that you are going in the right direction.

This applies to robots as well as people. It may be redundant for the mail delivery person to measure his position, but it may be important to the water mains repairman, who wants to make sure that he is not breaking down walls just to find out where the pipes should go. It may also be useful to the night watchman, who becomes able to create automatic reports of his position and any event that may have occurred there (none, if all goes well).

Localization, or the problem of estimating spatial relationships among objects, has been a classical problem in many disciplines, including mobile robotics (Thrun et al., 2001), virtual reality systems (Welch et al., 1999), navigation systems (VOR), and cellular networks (RAD).

Buildings can have a small area but several floors. These may have the same physical characteristics, but different information associated with them. For the security manager, it makes sense to schedule more rounds on the floor where the engineers sit than where accounts receivable are handled, simply because it is more likely that the engineers handle more sensitive company material — maybe even prototypes. Connecting the indoor location system to an inventory tracking system, marking all sensitive objects with radio frequency identification (RFID) tags, makes sense.

Buildings can also be large structures that cover a big area, but do not have a large extent in height. America is home to the biggest malls in the world, and it makes sense to know where in the mall you are — and where you are going. This is a typical indoor positioning application, which may be equally useful for the delivery person as for the “mall rat” who wants to find his friends.

Positioning systems range from an object is closest to (for example, which shelf in a warehouse a pallet is stacked on) or record when an object crosses a boundary (such as leaving a lot) to sophisticated systems that can determine precise location using multiple readers with overlapping fields of view. You can build indoor positioning systems in many ways, for instance, embedding bar codes where they can be conveniently read, but even if the bar code tags cost next to nothing, you are dependent on finding them to measure your position. This means that the position is only available in certain places, which may be a problem if you are moving along a path and get momentarily distracted (for instance, by an object placed in the path). In this regard, it is better to have a system that enables you to measure your position independently of the location in the building (i.e., you do not have to be close to the positioning device).

This means some kind of field or radiation, and while there are several types available, this book will look more deeply into those that are based on standards and that are practical to deploy, which means radio-based systems. For comparison, we will look into the MIT Cricket system, which uses a combination of radio and ultrasound.

For local-area requirements, such as tracking pallets in a warehouse, people within a building, or vehicles within a limited range of movement, indoor positioning technologies are better suited when compared to wide or global systems like GPS. Examples include triangulation within a wireless local-area network (WLAN) or proximity sensors, including RFID. RFID systems include relatively simple approaches that basically determine which reader is used or accessed. The most economical way to enable indoor positioning is to piggyback it on top of other systems that are used for the communication in the building. It is possible to build dedicated systems, using, for instance, pseudolites, which send out a simulated GPS signal, but this becomes expensive if a large area is to be covered, and the risk of interference with the true GPS signal has to be managed carefully. It makes more sense to use the wireless LAN, which probably is set up in the building anyway.

But placing positioning beacons is only the first step. Once you have determined the positions and made them available to whomever is to do the positioning, you have to relate that position to something. Knowing you are on the sixth floor in Room 135 does not help you much if you do not know how to get where you are going from there. It is even worse if all you know is that you are at a set of coordinates.

This means creating an application on top of the positioning system that can easily be filled with information, and that this information can as easily be retrieved. Actually, it means several applications (for instance, one for the acquisition of information, another for the authorization and authentication, and so on). In addition, you probably want to import information from existing databases and map systems into the application — so you do not have to recreate them. This may mean importing building drawings, which is not just a matter of mapping coordinate points to images, but if it is to work well, it has to involve some more thinking/work.

There is a tendency in the (nascent) indoor location industry to think that you can deliver monolithic applications — systems that in themselves contain everything. This may work for deployments where the vendor is in charge of everything, but it is a model that the wide-area location industry has long left behind. Nobody today even imagines the GPS device provider to be the same as the provider of maps, or the route calculation application. By introducing interfaces between the different components, the industry has taken off since the horizontal specialization lets each part of the chain do what it is best at.

Corresponding interfaces do exist for local-area systems, and we point them out in this book. But much standardization remains for them to be a viable alternative to the totally integrated — or “stovepipe” — solutions.

APPLICATION EXAMPLES AND USE CASES

With the advent of the GPS and the availability of chip-size GPS receivers, all future mobile wireless nodes can be equipped with the knowledge of their location. A user’s location will become information that is as common as the date is today, getting input from GPS when outdoors and other location-providing devices when indoors. Availability of location information will have a broad impact on the application level as well as on network-level software. We already have many devices with some location/position awareness or capability — cell phones, personal digital assistants (PDAs), laptops, RFID tags. And we will see many devices that could have location awareness but currently do not — wireless phones (though the pager feature allows one to find it), printers, computers, iPods, bikes, cars, other types of vehicles, etc., as well as whole classes of hybrid products — WiFi cellular phones and iPod handsets, for instance. Plus, we will get further degrees of integration with the devices we find common — a compass or gyroscope in a cell phone, accelerometers in laptops (IBM already has one, I think), etc. Things that sense motion or change in azimuth in conjunction with other location-aware devices. Accurate location-tracking technology helps support a range of wireless applications, such as E911 for tracking voice over wireless phones and wireless asset management. An increasingly popular use of mobile devices is to allow a user the ability to interact with his physical surroundings. For example, handheld computers can provide the user with information on topics of interest near the user, such as restaurants, copy centers, or automated teller machines. Similarly, mobile computers seek to allow a user to control devices located in close proximity to that computer, such as a printer located in the same room. Additionally, specialized computing devices, such as navigational systems found in many automobiles, seek to provide the user with directions based on the user’s current location. Also, pushing local information (i.e., in location-based advertising applications) increases business in that companies often have local information that is beneficial for users to have, especially when users are residing within specific areas. If a user’s position is known, a central server can then send valuable information to the user based on that location. As the user moves into different areas, the information sent to the user can then change accordingly.

Location-based service (LBS) applications include intelligent information management in Wi-Fi hot spots. A traveler gets off a plane at Boston’s Logan Airport and turns on his Wi-Fi-enabled PDA, for example, and immediately the local network pushes out floor plans of the airport, flight and ground transport information, and directions to — or, more ominously, ads from — on-site restaurants and shopping. Airports, for example, can offer to public wireless LAN subscribers client software that shows passengers how to find specific gates, baggage claims, restrooms, and customer service counters. In addition, location-based advertising that identifies where to find the nearest coffee shop or restaurant is possible. Microsoft has launched a web service — MS Location WiFi Finder — that allows Wi-Fi users to obtain details of their location and access to local information. The locations of Wi-Fi access points are pre-recorded (see war driving in Chapter 3) and stored in a database as part of the MapPoint System, which in turn is part of MS Local Live (previously known as Virtual Earth).

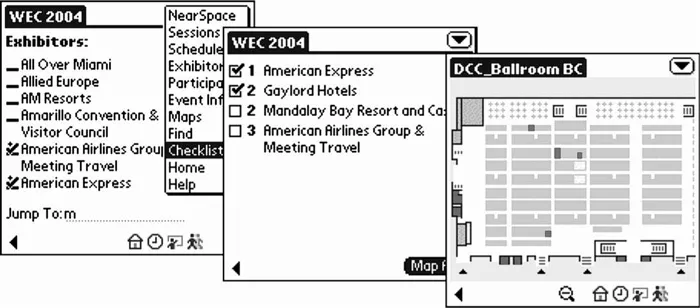

LBS products can, for example, provide convention center guests with specific directions from one wing of the facility to another, as shown in Figure 1.1. Figure 1.2 shows how attendees can locate sessions, exhibitors, and event services on dynamic maps and floor plans. The exhibition and conference industry constitutes another information-rich environment where indoor mobile location services can be deployed. The growing size of exhibitions (for example, CeBIT 2001, which is the leading event in the IT industry, occupied 432,000 m2 of space and attracted more than 830,000 visitors in eight days) naturally creates the need to develop new applications that will benefit visitors, exhibitors, and exhibition organizers alike. The development of applications based on indoor mobile communication technologies will probably transform the modus operandi of the exhibition industry in fundamental ways. Visitors will be able to register their personal preferences before visiting the exhibition (for example, through home or work access to an exhibition server). Upon entering the exhibition premises, they will receive a personal hand-held wireless device through which they will be able to obtain information about a particular stand or product, receive personalized notifications by the exhibition organizers (for example, notifications about events that are about to start), navigate along a predefined route generated by the system (based on expressed interests), schedule appointments with exhibitors, and so on. Exhibitors will also benefit by arranging and distributing marketing material more effectively, and by achieving personalized service, thus paving the way for more efficient customer relationship management (CRM). Finally, the exhibition organizers will be able to organize their work force according to events that might occur, provide announcements for specific target groups in a “silent” mode (through the hand-held device), and provide ex post statistics to their clients (i.e., the exhibitors).

An LBS makes it possible for a centralized server application to track users and assets. For example, a user’s PDA can continuously provide position updates. Universities are very interested in this form of LBS. Areas such as classrooms can be places where a school can block access to the Internet and the ability for students to use chat to share test answers. Of course, the more intelligent students could still use an ad hoc form of wireless LAN connectivity for communicating with their neighbors.

In hospitals, staff attach a small radio frequency identification (RFID) tracking device to all the babies that are born. This device is very difficult to remove, and sensors within that area of the hospital track the location of the baby. If anyone moves the baby outside an invisible perimeter (which is just before entering the exit areas of the labor-and-delivery unit), an alarm goes off and the system automatically secures all relevant exits. This makes it very difficult for anyone to steal babies, which happens more often than you would think in some hospitals.

Even without the use of a central server, an LBS makes sense for tracking applications. In this somewhat peer-to-peer form of LBS, users exploit the location of other users to make better decisions. For example, emergency crews responding to natural disasters and terrorist attacks can keep abreast of each other’s positions to effectively handle a situation. Each person can carry a PDA that shows the relative location of others.

Manufacturing and logistical operations throughout the supply chain need to efficiently manage numerous logistical optimizations to cut cost and time to market. Manual tracking of assets is labor-intensive and error-prone. Ekahau RTLS solutions let manufacturing plants, warehouses, and distribution centers monitor and manage the movement of work in process, inventory, tools, equipment, and key personnel. Using Ekahau’s solutions in manufacturing and supply chain management increases throughput, reduces turnaround times, optimizes equipment utilization, and increases staff productivity. Figure 1.3 portrays the overall possibilities.

PEOPLE/ASSET MANAGEMENT AND TRACKING

Asset management is often suggested as an application of location tagging, the idea being that it is possible to keep an inventory of assets and their locations to make it easier to find assets when needed. Wi-Fi or RFID tags enable the wireless network infrastructure to locate people and assets otherwise not connected to a wireless network. The tag can be used to track people in many valuable applications — child tracking in amusement parks, security personnel in enterprises, hospital patients, tracking the location and motion of consumers carrying a mobile communications device in a commercial retail establishment, employees in office buildings, equipment and parcels in a manufacturing or shipping facility, or attendees at a conference in a convention center. Various types of equipment can be tagged, including vehicles in parking lots; inventory in a manufacturing line; containers, forklifts, and other assets for efficient supply chain management; shopping carts in supermarkets; and medical equipment in hospitals. Some examples include:

Find a person: Ekahau Finder is an end-user web applicatio...