![]()

1

Introduction to Convergent Disciplines in Optical Engineering: Nano, MOEMS, and Biotechnology

Representative examples of the evolving interrelationships of optics, nanotechnology, microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), micro-opto-electromechanical systems (MOEMS), and biotechnology include

Digital image processing of optical imagery from high-speed cameras and x-ray illumination for real-time x-ray cineradiography

Optical signal processing for super high-speed computing

Physiology of the cell molecule mitochondria where messenger RNA generate proteins and signaling system pathways in response to impulse functions characterized with optical fiber sensor instrumentation

Laser illumination with spatiotemporal filtering to see through fireballs

Velocity and surface deformation measurement with fiber-optic Doppler sensing

Mach–Zehnder interferometric logic gate switches for high-speed computing

Flash x-ray cineradiographic event capture at the interface between mechanical structures and biophysiologic entities

Nanoassembly of protein structures for protein binding to specific steps in metabolic processes

Additional applications of optical engineering to biotechnology of particular interest include bioimaging, biosensors, flow cytometry, photodynamic therapy, tissue engineering, and bionanophotonics, to name a few. Such are the applications of the future. This book is intended to extend the fields of optical engineering and solid-state physics into the realms of biochemistry and molecular biology and to ultimately redefine specialized fields such as biophotonics. It is in such crossdisciplinary endeavors that we may ultimately achieve some of the most significant breakthroughs in science.

The parallels in solid-state physics and engineering to biochemistry are enlightening. For instance, models for electron transport through respirasomes are analogous to the energetic transport of electrons in solid-state physics. The semiconductor model involves electrons in the valence band, excited to the conduction band, and essentially hopping along the crystal matrix through successive donor–acceptor energetics. In the semiconductor, “pumping” or increasing the electron energy across a band gap is necessary for electron transport, while in the biochemical model the proton-motive force across a membrane supplies the “pump.”

Each mechanism exhibits its own electron transport stimuli, for instance, increased nano-ordering of water in a hydrogen-bonded contiguous macromolecule serving to “epigenetically” influence the transport of ions across a cell membrane or to influence protein folding. What are the light-activated switching mechanisms in proteins? Are there aspects of epigenetic programming that can be “switched” with light? If we “express” such a protein in a cell, can we then control aspects of the protein’s behavior with light?

Consider the analogy of the progression of signal processing using combinations of digital logic gates and application-specific integrated circuits to optical signal processing using operator transforms, optical index, and nonlinear bistable functions through acousto- and electro-optic effects to perform optical computing; to Dennis Bray’s “Wetware” biologic cell logic [1]; and to the astounding insights of Nick Lane in the last two chapters of his recent “Life Ascending—the Ten Great Inventions of Evolution” [2], where Lane characterizes the evolutionary development of consciousness and death (through the mitochondria), providing the basis for the biological logic and how best to modify and control that inherent logic (see Chapter 7, Section 7.5.5).

We are on the cusp of an epoch, where it is now possible to design light-activated genetic functionality, to actually regulate and program biological functionality. What if, for instance, we identify and isolate the biological “control mechanism” for the switching on and off of limb regeneration in the salamander, or, with the biophotonic emission associated with cancer cell replication, and analogous to the destruction of the cavity resonance in a laser, we reverse the biological resonance and switch or epigenetically reprogram the cellular logic?

Scaffolds are three-dimensional nanostructures fabricated using laser lithography. Perhaps, complex protein structures could be assembled onto these lattices in a preferred manner, such that introduction of the lattice frames might “seed” the correct protein configuration. This inspires the concept of biocompatible nanostructures for “biologically inspired” computing and signal processing, for example, biosensors in the military, or for recreating two-way neural processes and repairs.

By spatially recruiting metabolic enzymes, protein scaffolds help regulate synthetic metabolic pathways by balancing proton/electron flux. This represents a synthesis methodology with advantages over more standard chemical constructions. It is certainly something to look forward to in future biotechnology and biophotonics developments.

We previously designed sequences of digital optical logic gates to remove the processing bottlenecks of conventional computers. But if we now look to producing non-Von Neumann processors with biological constructs, we may truly be at the computing crossroad for the “Kurzweil singularity.”

A recent article in Wired magazine entitled “Powered by Photons” [3] described the emerging field of opto-genetics in understanding how specific neuronal cell types contribute to the function of neural circuits in vivo—the idea that two-way optogenetic traffic could lead to “human–machine fusions in which the brain truly interacts with the machine rather than only giving or only accepting orders….” The fields of proteomics, genomics, epigenetic programming, bioinformatics, nanotechnology, bioterrorism, pharmacology, and related disciplines represent key technology areas. These are the sciences of the future.

References

1. Bray, D. 2009. Wetware: A Computer in Every Living Cell. New Haven: Yale University Press.

2. Lane, N. 2009. Life Ascending: The Ten Great Inventions of Evolution. New York: W.W. Norton and Co.

3. Chorost, M. November 2009. Powered by photons. Wired.

![]()

2

Electro-Optics

2.1 Introduction

Developing communication, instrumentation, sensors, biomedical, and data processing systems utilize a diversity of optical technology. Integrated optics is expected to complement the well-established technologies of microelectronics, optoelectronics, and fiber optics. The requirements for applying integrated optics technology to telecommunications have been explored extensively and are well documented [1]. Other applications include sensors for measuring rotation, electromagnetic fields, temperature, pressure, and many other phenomena. Areas that have received much recent attention include optical techniques for feeding and controlling GaAs monolithic microwave integrated circuits (MMIC), optical analog and digital computing systems, and optical interconnects for improving integrated system performance [2].

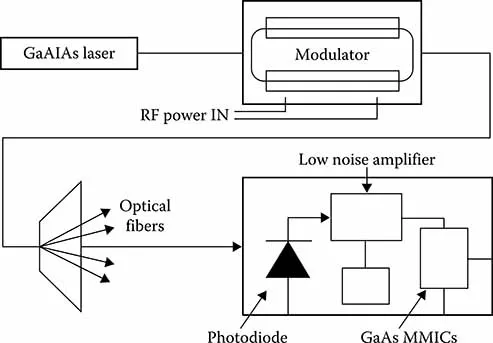

An example of an MMIC application [3] is a fiber-optic distribution network interconnecting monolithically integrated optical components with GaAs MMIC array elements (see Figure 2.1). The particular application described is for phased array antenna elements operating above 20 GHz. Each module requires several RF lines, bias lines, and digital lines to provide a combination of phase and gain control information, presenting an extremely complex signal distribution problem. Optical techniques transmit both analog and digital signals as well as provide small size, light weight, mechanical stability, decreased complexity (with multiplexing), and large bandwidth.

An identical RF transmission signal must be fed to all modules in parallel. The optimized system may include an external laser modulator due to limitations of direct current modulation. Much research is needed to develop the full compatibility of MMIC fabrication processes with optoelectronic components. One such device being developed is an MMIC receiver module with an integrated photodiode [4]. Use of MMIC foundry facilities for fabrication of these optical structures is discussed in Section 5.11.

Another application area that can significantly benefit from monolithic integration is optically interconnecting high-speed integrated chips, boards, and computing systems [5]. There is ongoing demand to increase the throughput of high-speed processors and computers. To meet this demand, denser higher speed integrated circuits and new computing architectures are constantly developed. Electrical interconnects and switching are identified as bottlenecks to the advancement of computer systems. Two trends brought on by the need for faster computing systems have pushed the requirements on various levels of interconnects to the edge of what is possible with conventional electrical interconnects. The first trend is the development of higher speed and denser switching devices in silicon and GaAs. Switching speeds of logic devices are now exceeding 1 Gb/s, and high-density integration has resulted in the need for interconnect technologies to handle hundreds of output pins. The second trend is the development of new architectures for increasing parallelism, and hence throughput, of computing systems.

FIGURE 2.1

Optical signal distribution network for MMIC module RF signals.

A representation of processor and interconnect complexity for present and proposed computing architectures [6] is shown in Figure 2.2.

The dimension along the axis is the number of proc...