eBook - ePub

The Origin of Higher Clades

Osteology, Myology, Phylogeny and Evolution of Bony Fishes and the Rise of Tetrapods

- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Origin of Higher Clades

Osteology, Myology, Phylogeny and Evolution of Bony Fishes and the Rise of Tetrapods

About this book

The book provides insight on the osteology, myology, phylogeny and evolution of Osteichthyes. It not only provides an extensive cladistic analysis of osteichthyan higher-level inter-relationships based on a phylogenetic comparison of 356 characters in 80 extant and fossil terminal taxa representing all major groups of Osteichthyes, but also analyses various terminal taxa and osteological characters. And also provides a general discussion on issues such as the comparative anatomy, homologies and evolution of osteichthyan cranial and pectoral muscles, the development of zebrafish cephalic muscles and the implications for evolutionary developmental studies, the origin homologies and evolution of one of the most peculiar and enigmatic structural complexes of osteichthyans, the Weberian apparatus, and the use of myological versus osteological characters in phylogenetic reconstructions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Origin of Higher Clades by Rui Diogo in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780429526626Subtopic

BiologyChapter 1

Introduction and Aims

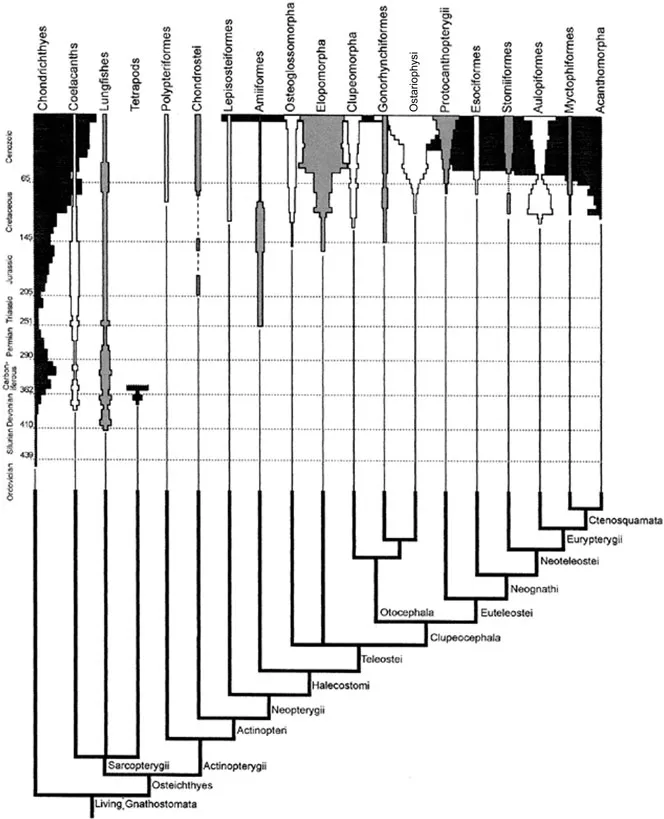

The Osteichthyes, including bony fishes and tetrapods, is a highly speciose group of animals comprising more than 42,000 living species. Two main osteichthyan groups are usually recognized: the Sarcopterygii (lobefins and tetrapods), with an estimate of more than 24,000 living species (e.g., Stiassny et al., 2004), and the Actinopterygii (rayfins), including more than 28,000 extant species (e.g., Nelson, 2006). The extraordinary taxonomic diversity of osteichthyans is associated with a remarkable variety of morphological features and adaptations to very different habitats, from the deep sea to high mountains. In this brief Introduction, I will not provide a detailed historical account of all the numerous works dealing with osteichthyan phylogeny. Such information can be found in overviews such as Arratia (2000: relationships among major teleostean groups), Clack (2002: relationships among major groups of early tetrapods), Stiassny et al. (2004: relationships among major groups of gnathostome fishes), Cloutier and Arratia (2004: relationships among early actinopterygians), and Nelson (2006: relationships among numerous fish groups). I prefer simply to give the reader a general idea of the phylogenetic scenario that is nowadays most commonly accepted in textbooks concerning the relationships between the major osteichthyan groups, which is shown in Fig. 1. Further details about this subject will be given in Chapter 3, in which I will discuss each of these groups separately and compare the phylogenetic results obtained in this work with those of previous studies.

The extant vertebrates that are usually considered to be the closest relatives of osteichthyans are the chondrichthyans (Fig. 1). However, it should be stressed that according to most authors there is a group of fossil fishes that is even more closely related to osteichthyans: the †Acanthodii, which, together with the Osteichthyes, form a group usually named Teleostomi (e.g., Kardong, 2002). In addition, it should be noted that apart from the Teleostomi and Chondrichthyes, there is another group that is usually included in the gnathostomes and that is usually considered the sister-group of teleostomes + chondrichthyans: the †Placodermi (e.g., Kardong, 2002). There are only two groups of extant sarcopterygian fishes, the coelacanths (Actinistia) and lungfishes (Dipnoi) (Fig. 1). The Polypteridae (included in the Cladistia) are commonly considered the most basal extant actinopterygian taxon (Fig. 1). The Acipenseridae and Polyodontidae (included in the Chondrostei) are usually considered the sister-group of a clade including the Lepisosteidae (included in the Ginglymodi) and the Amiidae (included in Halecomorphi) plus the Teleostei (Fig. 1). Regarding the Teleostei, four main living clades are usually recognized in recent works: the Elopomorpha, Osteoglossomorpha, Otocephala (Clupeomorpha + Ostariophysi) and Euteleostei (Fig. 1).

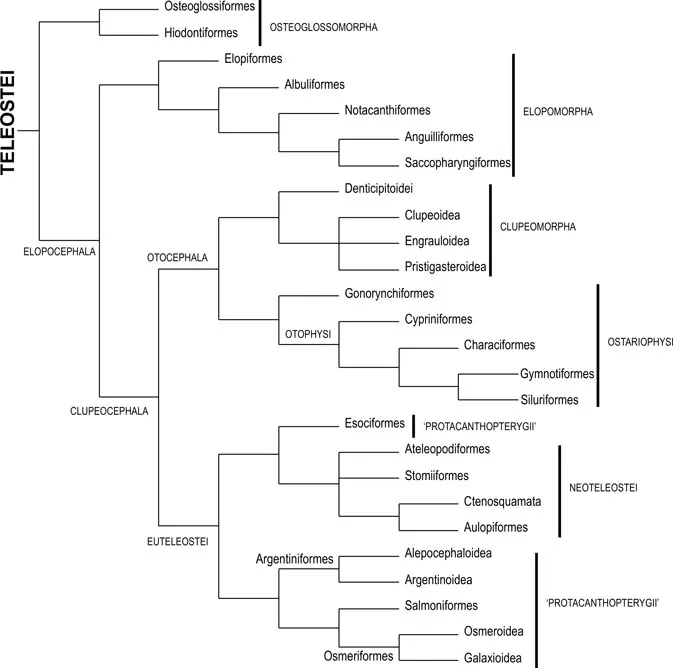

In order to provide more detail on the various subgroups of these four teleostean clades, I will refer to a cladogram provided by Springer and Johnson (2004), which, in my opinion, adequately summarizes the scenario that is probably accepted by most researchers nowadays. A simplified version of this cladogram is shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen, among these four teleostean groups the Osteoglossomorpha appears as the most basal one, the Elopomorpha appearing as the sister-group of Otocephala + Euteleostei (Fig. 2). Within the Euteleostei, the Esociformes are placed closely related to the Neoteleostei, although many authors consider the esociforms as part of the “Protacanthopterygii” (see below). Other fishes usually included in the “Protacanthopterygii” are the Alepocephaloidea, the Argentinoidea, the Salmoniformes, the Osmeroidea, and the Galaxioidea.

As stressed by Springer and Johnson (2004) and Stiassny et al. (2004), on whose works Figs. 1 and 2 are based, although the scenarios shown in those figures are widely accepted nowadays, they are far from being agreed upon by all specialists. For instance, Filleul (2000) and Filleul and Lavoué (2001) argued that the Elopomorpha is in fact not a monophyletic unit. Ishiguro et al. (2003) and other authors maintained that the Otocephala, as currently recognized (Ostariophysi + Clupeomorpha), is also not monophyletic, since certain otocephalans are more closely related to the “protacanthopterygian” alepocephaloids than to other otocephalans. Also, contrary to what is accepted by most authors (Fig. 2), Ishiguro et al. (2003) suggested that the non-alepocephaloid “protacanthopterygians” (sensu these authors, that is, the Esociformes, Salmoniformes, Osmeriformes and Argentinoidea) form a monophyletic, valid “Protacanthopterygii” clade. To give another example, Arratia (1997, 1999) argued that the most basal extant teleostean group is the Elopomorpha, and not the Osteoglossomorpha, as shown in Fig. 2. In fact, as can be seen in Fig. 1, in contrast with Springer and Johnson (2004), Stiassny et al. (2004) opted to place the Osteoglossomorpha, Elopomorpha and remaining teleosts in an unresolved trichotomy. And, as can also be seen in that figure, this is not the only trichotomy appearing in Stiassny et al.’s (2004) cladogram.

The other trichotomy appearing in that cladogram concerns one of the most discussed topics in osteichthyan phylogeny: that concerning the identity of the closest living relatives of the Tetrapoda (Fig. 1). This topic has been, and continues to be, the subject of much controversy. In general textbooks such as those by Lecointre and Le Guyader (2001), Kardong (2002) and Dawkins (2004), the tetrapods often appear more closely related to lungfishes than to the coelacanths. This view has been defended, at least partly, in many morphological and molecular works, such as those by Rosen et al. (1981), Patterson (1981), Forey (1980, 1991), Cloutier and Ahlberg (1996), Zardoya et al. (1998), Meyer and Zardoya (2003), and Brinkmann et al. (2004). However, researchers such as Zhu and Schultze (1997, 2001), on the basis of anatomical studies, defended a closer relationship between tetrapods and coelacanths than between tetrapods and lungfishes. And Zardoya and Meyer (1996) and Zardoya et al. (1998), on the basis of molecular analyses, have inclusively suggested that coelacanths and lungfishes may be sister-groups. A completely different scenario has been defended in a series of molecular works by Arnason and colleagues (Rasmussen and Arnason, 1999a,b; Arnason et al., 2001, 2004): that tetrapods are the sister-group of a clade including taxa such as lungfishes, cladistians, coelacanths, sharks and teleosts. Nevertheless, it should be said that the methodology and the results of these latter works have been severely criticized and questioned by numerous researchers (see below).

In light of all this controversy, Stiassny et al. (2004) opted to place coelacanths, lungfishes and tetrapods in an unresolved trichotomy inside the sarcopterygian clade (Fig. 1). In other words, they considered that the data currently available does not allow us to suitably answer two fundamental questions concerning two of the most highly diverse osteichthyan groups, the Tetrapoda and Teleostei: Which is the closest living relative of tetrapods? And which is the most basal extant teleostean clade? And, as stressed by Stiassny et al. (2004), “although most workers have followed Patterson (1973) in the recognition of Amia as the closest living relative of the Teleostei, there remains some controversy” about the phylogenetic position of this taxon. Actually, according to Grande (2005), an extensive study in progress done by Grande and Bemis supports the hypothesis that, contrary to what is often accepted nowadays (see Fig. 1), the Halecomorphi (including the Amiidae) may be more closely related to the Ginglymodi (including the Lepisosteidae) than to the Teleostei. Such a view has also been supported by molecular studies by Inoue et al. (2003) and Kikugawa et al. (2004). Thus, another fundamental question concerning one of these two highly diverse osteichthyan groups remains disputed: which are the closest living relatives of teleosts, the amiids of the genus Amia, or both these fishes and the lepisosteids of the genera Lepisosteus and Atractosteus, that is, the members of the three extant genera of an eventual clade Halecomorphi + Ginglymodi? Together with what was mentioned above about the controversies regarding the monophyly/non-monophyly of the Elopomorpha, the Otocephala, and the “Protacanthopterygii”, these are just a few examples to illustrate that, in fact, despite the progress achieved in osteichthyan phylogeny in the last decades, some crucial questions concerning this subject do remain unresolved and highly debated.

Le et al. (1993) and Meyer and Zardoya (2003) have stated that in order to help resolve such crucial questions it is extremely important to promote “new morphological character analyses”. In fact, apart from the obvious need for new studies using, and combining, different types of molecular data and, very important, including more terminal taxa than the few species usually included in most molecular studies, I also consider that there is an imperative need for new, fresh morphological cladistic analyses to help clarify osteichthyan higher-level phylogeny. When one reads certain recent molecular works, it may appear that morphologists have already played all their cards regarding the resolution of major issues on the phylogeny of groups such as osteichthyans. In my opinion, this is clearly not the case.

First of all, many studies have focused on the anatomy of representatives of the major osteichthyan groups, but much of the vast amount of anatomical data available has unfortunately not been used to promote explicit cladistic analyses (Diogo, 2004a). To put it more simply, a certain researcher may describe in detail a region of the body of a certain taxon A, and may even compare it with the same region of the body of a certain taxon B. In many cases, however, this anatomical data is ultimately not used to promote a cladistic study in which are included not only taxa A and B but also other taxa, and in which all the data available is presented in the form of phylogenetic characters that then allow the building of a phylogenetic matrix that is, in turn, analyzed under an explicit cladistic procedure.

Another important point is that among the unfortunately few explicit morphological cladistic analyses published so far on osteichthyans, the great majority are focused on a single family, a single subfamily, or even a single genus (Diogo, 2004a). Such studies are of course needed and much welcomed. But the fact is that explicit cladistic studies using a high number of characters and a high number of representatives of various osteichthyan orders are very rare. And including terminal taxa from osteichthyan groups as varied as, for example, the Teleostei, the Halecomorphi, the Ginglymodi, the Chondrostei, the Cladistia, the Actinistia, the Dipnoi, and the tetrapods, as in the present work, is even more rare. As stressed by Le et al. (1993) and Ishiguro et al. (2003), the consequence of this is that certain major osteichthyan clades that are generally accepted by morphologists, and by other researchers as well, have in reality never been supported by explicit morphological cladistic analyses. I will provide some examples of this in Chapter 3.

Another aspect pointed out by Diogo (2004a,b) is that most morphological cladistic analyses that have been published so far on osteichthyans concern mainly osteological and/or external characters. Very few of them include a significant number of myological characters, not even those dealing exclusively with extant terminal taxa. At least to my knowledge, there is not a single morphological cladistic analysis published on osteichthyan higher-level phylogeny that has included a great number of both osteological and muscular characters.

In summary, in my opinion morphologists have clearly not played all their cards for the resolution of major issues regarding osteichthyan phylogeny: (1) there is a vast amount of anatomical data already available in the literature that could be used in explicit cladistic analyses; (2) an effort could also be made to promote cladistic analyses including representatives of various major osteichthyan groups, in order to test whether the higher clades often accepted in the literature are, or are not, supported by these analyses; and (3) an effort could be made to include other types of anatomical characters, for example, myological ones, in such cladistic analyses, since much useful anatomical information is being lost in using mainly osteological characters.

One of the main aims of the present work is precisely to provide a cladistic analysis that includes terminal taxa from osteichthyan groups as varied as the Teleostei, Halecomorphi, Ginglymodi, Chondrostei, Cladistia, Actinistia and Tetrapoda, and that includes a large number of both osteological and myological characters. This may make it possible, for instance, to check whether the major osteichthyan clades shown in Figs. 1 and 2 are in fact supported by such a cladistic analysis. The inclusion of a great number of both osteological and myological characters may also allow us to compare how these different types of characters behave in the phylogenetic study, for example, to see which characters provide better support for the major clades obtained in the study or which characters appear to be more homoplasic within these clades. Such issues have unfortunately not been much discussed in the literature (Diogo, 2004a,b). According to Diogo (2004a,b), myological characters may play an important role in phylogenetic reconstructions, particularly in those concerning the relationships of higher clades. One of our aims here is thus to discuss whether or not the results of the cladistic analysis of the present work, which is precisely focused on the higher-level phylogeny of a major group such as the osteichthyans, support such a view. The inclusion of muscular characters in a study such as the present one may also pave the way for a more detailed, integrative reflection on the functional morphology and evolution of, for example, the pectoral girdle or the head (Winterbottom; 1993; Galis, 1996; Borden, 1998, 1999; Diogo, 2004a). It is important to emphasize that structural complexes are constituted by a set of integrated bones, but also muscles, cartilage and ligaments. For this reason, as well as for the other reasons that will be given in these first two chapters, the characters examined in the present work concern not only the configuration of bones, but also that of numerous muscles, cartilage and ligaments.

It should be stressed that the cladistic analysis provided in this work refers essentially to the higher-level relationships among the major basal groups of the sarcopterygian and actinopterygian lineages, and not to the interrelationships between the various taxa of highly diverse, derived extant groups such as the actinopterygian neoteleosts and the sarcopterygian tetrapods. As explained above, this cladistic analysis does include some representatives of these two groups, but with the main aim of searching for the higher-level relationships between these groups and other major osteichthyan clades. A detailed morphological cladistic analysis of the relationships among the numerous teleostean subgroups and among the numerous tetrapod taxa would require at least two books such as this one. But I do hope that the present work will pave the way for such analyses. For instance, the results obtained here may help to clarify which of the taxa examined may be more closely related to neoteleosts and to tetrapods and may thus help in choosing appropriate outgroups and polarizing characters in future works on the interrelationships among the various subunits of these two groups.

These results can also help to clarify the origin and homologies of certain structures found in the members of these groups, for example, the peculiar tongue muscles found in most tetrapods. One of the main goals of the book is to provide a new insight into the homologies and evolution of certain key osteological and myological structures examined, taking into account the phylogenetic results obtained. I consider that it is particularly important to give a fresh look to the homologies and evolution of osteichthyan muscular structures, which have been much less studied and discussed than the osteological ones. The most extensive, detailed compa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction and Aims

- 2. Methodology and Material

- 3. Phylogenetic Analysis

- 4. Comparative Anatomy, Higher-level Phylogeny and Macroevolution of Osteichthyans—A Discussion

- References

- Index