R. Alan Cheville

1.1 INTRODUCTION TO TERAHERTZ SPECTRAL REGION

A recent report from the National Academies outlines that electronic and optics are combining to open up a new “Tera-Era.”1 This vision includes computers performing operations at rates of teraflops, terabit-per-second communication systems, and electronic devices on the picosecond time scale. From a spectroscopic point of view, the terahertz (THz) spectral region from 300 GHz (λ = 1 mm) to 10 THz (λ = 30 µm) has not yet seen the technological development of optical or microwave frequencies with the result that commercial spectrometers covering the entire spectral range are not yet widely available. This is primarily because of the difficulty of generating and detecting THz frequencies compared with the better-established technologies of optics and electronics.

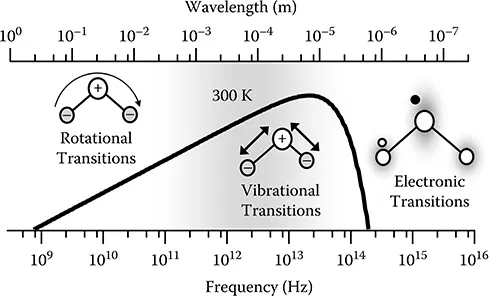

The so-called “THz gap” arises from the nature of the sources and detectors used in spectroscopy both at the optical (high-frequency) side and electronic (low-frequency) side of the gap. One terahertz corresponds to a photon energy of 4 meV (33.3 cm−1). These energies are much less than the electronic state transitions of atoms and molecules commonly used in lasers or other light sources (Figure 1.1). Semiconductor materials also have bandgaps on the order of an electron volt, orders of magnitude larger than THz energies.

FIGURE 1.1 The electromagnetic spectrum from microwave to optical region. The area easily accessible by THz spectroscopy using photoconductive sources is shown shaded in gray. Rotational, vibrational, and electronic transitions are shown along with the blackbody radiation curve at 300 K.

Vibrational frequencies, such as the 10.6 µm CO2 laser, and rotational transition frequencies do fall in the far infrared. Light sources based on these transitions exist, but typically cover limited frequency ranges.2 Thermal emission from incoherent blackbody radiation is one of the most commonly used sources since the thermal energy, kT, is about 25 meV at room temperature (300 K). The blackbody radiation curve and the relative spectral power emitted are shown as a black line in Figure 1.1. Scaling electronics to operate in the THz gap is limited by the frequency response of devices. The high-frequency limit is determined by the time it takes electrons to traverse the device, which is determined by the physical size and carrier mobility. Although feature sizes are continually shrinking, material properties ultimately limit high-frequency response. New semiconductor materials and the ability to confine carriers at the quantum level are leading to high-speed devices pushing into the THz gap. Some exciting recent developments are laser diodes,3 high electron mobility transistors, and quantum cascade lasers.4

The same physical limitations that arise in scaling optical sources down (or electronic sources up) to the THz spectral region also hold for detectors of THz radiation. THz photons cannot excite electrons into the conduction band in a photodiode (without multiphoton absorption, which would require unreasonable intensities) or provide enough energy to cause photoelectric emission of electrons. Although bolometers can detect radiation, they are limited by incoherent thermal background signals unless cooled to very low temperatures.

The far infrared spectrum and the points made previously are summarized in Figure 1.1. There is a great deal of interest in this spectral region ranging from creating faster electronic devices to the wealth of spectroscopic information available. THz spectroscopy provides information on the basic structure of molecules and is a useful tool of radio astronomy. Rotational frequencies of light molecules fall in this spectral region, as do vibrational modes of large molecules with many functional groupings, including many biologic molecules that have broad resonances at THz frequencies.

This chapter provides an overview of how the technologic difficulties inherent to THz generation and detection can be overcome through a synthesis of ultrafast optical and electronic techniques. By gating micron scale antennas on photoconductive substrates with femtosecond pulses, it is possible to generate and detect electromagnetic pulses with THz bandwidths.

1.2 BRIEF THEORETICAL BACKGROUND FOR PHOTOCONDUCTIVE TERAHERTZ GENERATION

Because THz radiation generated and detected through photoconduction arises from the flow of charge, it is theoretically described by Maxwell’s equations. Maxwell’s equations do not, however, describe the processes from which charge flow occurs on a femtosecond scale in semiconductors. This is a topic worthy of a complete book,5 and the description of processes from which charge flow arises are not gone into in detail here. From the perspective of THz generation, the source terms of Maxwell’s equations are written to show time-dependent terms explicitly by adding a (t) to them.

Here, μ(t)H(t) = B(t) is the magnetic flux, H(t)= σ(t)E(t) is the current density, and ε(t)E(t) = D(t) is the electric displacement. Any process that creates a time-dependent change in the material properties μ, σ, or ε can act as a source term that can result in emission of THz radiation. For THz generation using photoconductive switches, an ultrashort optical pulse incident on a semiconductor causes rapid transient changes to the macroscopic material properties represented by μ(t), σ(t), and ε(t). For the discussion that follows, the major change caused by the optical pulse is assumed to be in the conductivity, σ. The rapid, optically induced change of σ on a femtosecond time scale is the origin of ultrafast THz pulses generated through photoconduction as well as the physical mechanism by which the THz pulses are detected. It is important to note that many physical processes occur when ultrafast optical pulses are absorbed by semiconductors, and, from an experimental viewpoint, they are not easily separable. Both resonant (absorption of a photon to create charge carriers, σ) and non-resonant (nonlinear optical difference frequency generation, ε) effects can contribute to THz pulse generation. A common example of a material in which both processes contribute to THz generation is gallium arsenide (GaAs).

The driving term, σ(t), in Maxwell’s equations results from an ultrafast optical pulse that impulsively excites the semiconductor. The resulting electric and magnetic fields created through the time-dependent conductivity have fast transients with correspondingly broad spectral bandwidths. The spectral bandwidth can be estimated from the uncertain relation [between the bandwidth, Δω, required to support a transient signal] Δt. Because ΔtΔω ≥ ½, a 1-ps excitation pulse requires, and can create, spectral bandwidths on the order of 0.3 THz, whereas a 100-fs transient has a bandwidth of at least 3 THz. With sub-10-fs pulses readily available from current commercial ultrafast lasers, very broad spectral coverage of the THz region has been achieved.

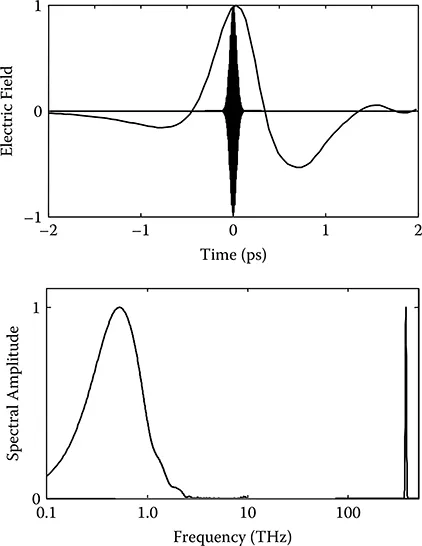

FIGURE 1.2 Electric field of a measured THz pulse and the simulated field of the exciting optical pulse are shown in the upper figure, whereas the amplitude spectrum is shown in the lower figure.

An example of a THz measurement from the author’s laboratory is shown in Figure 1.2. The upper figure compares the measurement of the electric field of a THz pulse in the time domain with the numerically calculated electric field of the 50-fs optical pulse at 800 nm used to generate the THz pulse. The rapidly oscillating carrier frequency of the optical pulse makes it appear to be a filled Gaussian envelope. The spectral amplitude of the THz pulse and optical pulse are shown in the lower figure. Although the actual bandwidth of the optical pulse (10.6 THz) is considerably larger than that of the THz pulse (0.7 THz), the THz pulse spans a greater fraction of the electromagnetic sp...