1.1 Introduction

Viewed from one perspective, one can say that, like life itself, ultrasonics came from the sea. On land, the five senses of living beings (sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste) play complementary roles. Two of these, sight and hearing, are essential for long-range interaction, while the other three have essentially short-range functionality. But things are different under water; sight loses all meaning as a long-range capability, as does indeed its technological counterpart, radar. So, by default, sound waves carry out this long-range sensing function under water. The most highly developed and intelligent forms of underwater life (e.g., whales and dolphins) over a time scale of millions of years have perfected very sophisticated range finding, target identification, and communication systems using ultrasound. On the technology front, ultrasound also really started with the development of underwater transducers during World War I. Water is a natural medium for the effective transmission of acoustic waves over large distances, and it is indeed, for the case of transmission in opaque media, that ultrasound comes into its own.

In this book, we are more interested in ultrasound as a branch of technology as opposed to its role in nature, but a broad survey of its effects in both areas will be given in this chapter. Human efforts in underwater detection were spurred in 1912 by the sinking of RMS Titanic by collision with an iceberg. It was quickly demonstrated that the resolution for iceberg detection was improved at higher frequencies, leading to a push toward the development of ultrasonics as opposed to audible waves. This led to the pioneering work of Langevin, who is generally credited as the father of the field of ultrasonics. The immediate stimulus for his work was the submarine menace during World War I. The United Kingdom and France set up a joint program for submarine detection, and it is in this context that Langevin set up an experimental immersion tank in the Ecole de Physique et Chimie in Paris. He also conducted large-scale experiments, up to 2 km long, in the Seine River. The condenser transducer was soon replaced by a quartz element, resulting in a spectacular improvement in performance, and detection up to a distance of 6 km was obtained. With Langevin’s invention of the more efficient sandwich transducer shortly thereafter, the subject was born. Although these developments came too late to be of much use against submarines in that war, numerous technical improvements and commercial applications followed rapidly.

But what, after all, is ultrasonics? Like the visible spectrum, the audio spectrum corresponds to the standard human receptor response function and covers frequencies from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, although, with age, the upper limit is reduced significantly. For both light and sound, the “human band” is only a tiny slice of the total available bandwidth. In each case, the full bandwidth can be described by a complete and unique theory, that of electromagnetic waves for optics and the theory of stress waves in material media for acoustics.

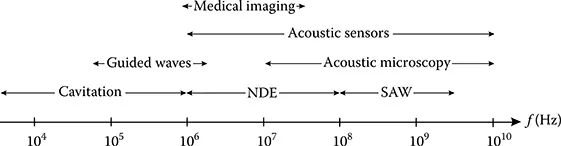

Ultrasonics is defined as that band above 20 kHz. It continues up into the megahertz range and finally, at around 1 GHz, goes over into what is conventionally called the hypersonic regime. The full spectrum is shown in Figure 1.1, where typical ranges for the phenomena of interest are indicated. Most of the applications described in this book take place in the range of 1 to 100 MHz, corresponding to wavelengths in a typical solid of approximately 1 mm to 10 μm, where an average sound velocity is about 5000 m/s. In water—the most widely used liquid—the sound velocity is about 1500 m/s, with wavelengths of the order of 3 mm to 30 μm for the above frequency range.

FIGURE 1.1 Common frequency ranges for various ultrasonic processes.

Optics and acoustics have followed parallel paths of development from the beginning. Indeed, most phenomena that are observed in optics also occur in acoustics. But acoustics has something more—the longitudinal mode in bulk media, which leads to density changes during propagation. All the phenomena occurring in the ultrasonic range occur throughout the full acoustic spectrum, and there is no theory that works only for ultrasonics. So the theory of propagation is the same over the whole frequency range, except in the extreme limits where funny things are bound to happen. For example, diffraction and dispersion are universal phenomena; they can occur in the audio, ultrasonic, or hypersonic frequency ranges. It is the same theory at work, and it is only their manifestation and relative importance that change. As in the world of electromagnetic waves, it is the length scale that counts. The change in length scale also means that quite different technologies must be used to generate and detect acoustic waves in the various frequency ranges.

Why is it worth our while to study ultrasonics? Alternatively, why is it worth the trouble to read (or write) a book like this? As reflected in the structure of the book itself, there are really two answers. First, there is still a lot of fundamentally new knowledge to be learned about acoustic waves at ultrasonic frequencies. This may involve getting a better understanding of how ultrasonic waves occur in nature, such as a better understanding of how bats navigate or dolphins communicate. Also, as mentioned later in this chapter, there are other fundamental issues where ultrasonics gives unique information; it has become a recognized and valuable tool for better understanding the properties of solids and liquids. Superconductors and liquid helium, for example, are two systems that have unique responses to the passage of acoustic waves. In the latter case, they even exhibit many special and characteristic modes of acoustic propagation of their own. A better understanding of these effects leads to a better understanding of quantum mechanics and hence to the advancement of human knowledge.

The second reason for studying ultrasonics is because it has many applications. These occur in a very broad range of disciplines, covering chemistry, physics, engineering, biology, food industry, medicine, oceanography, seismology, and so on. Nearly all of these applications are based on two unique features of ultrasonic waves:

Ultrasonic waves travel slowly, about 100,000 times slower than electromagnetic waves. This provides a way to display information in time, create variable delay, and so on.

Ultrasonic waves can easily penetrate opaque materials, whereas many other types of radiation such as visible light cannot. Since ultrasonic wave sources are inexpensive, sensitive, and reliable, this provides a highly desirable way to probe and image the interior of the opaque objects.

Either or both of these characteristics occur in most ultrasonic applications. We will give one example of each to show how important they are. Surface acoustic waves (SAWs) are high-frequency versions of the surface waves discovered by Lord Rayleigh in seismology. Because of their slow velocity, they can be excited and detected on a convenient length scale (cm). They have become an important part of analog signal processing, for example, in the production of inexpensive, high-quality filters, which now find huge application niches in the television and wireless communication markets. A second example is in medical applications. Fetal images have now become a standard part of medical diagnostics and control. The quality of the images is improving every year with advances in technology. There are many other areas in medicine where noninvasive acoustic imaging of the body is invaluable, such as cardiac, urological, and opthalmological imaging. This is one of the fastest growing application areas of ultrasonics.

1.2 Ultrasonics in Nature

We consider first the important case of ultrasonic communication by animals, including mammals, rodents, fish, birds, and so on. In fact, only a limited number of species use this capability and they mostly do so in environments where normal sensing mechanisms are not very effective, for example, night or underwater vision or where there is high background audible noise. The sensing functions include navigation and communication for group interaction or survival such as attracting mates, evading predators, or detecting prey. The relative importance of ultrasonics in the sensing arsenal of the animal will depend on such technical factors as attenuation, scattering, directionality, and so on as compared to audible or optical communication.

There has recently been heightened interest in this field mainly due to the use of highly controlled laboratory experiments. Often this involves surgical intervention to allow direct study of the animal’s sensing system, accompanied by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) mapping of the cervical areas involved in different functions. The laboratory also allows controlled modification of the environment, which gives complementary information to field observations. Development of improved ultrasonic instrumentation, microphones, and so on has also led to more refined experiments. Very recent work has also focused on breakthroughs in the genetic area.

In this short review, we begin with one of the most advanced practitioners of ultrasonics, the bat. This is followed by accounts of evasive measures developed by its prey, such as moths, mantis, and crickets. We then consider rodents, followed by frogs and the cetacean (whales, porpoises, and dolphins).The discussion is rounded out by the most spectacular of all, the snapping shrimp.

One of the best-known examples is ultrasonic navigation by bats, the study of which has a rather curious history [1]. The Italian natural philosopher Lazzaro Spallanzani published results of his work on this subject in 1794. He showed that bats were able to avoid obstacles when flying in the dark, a feat that he attributed to a “sixth sense” possessed by bats. This concept was rejected in favor of a theory related to flying by touch. In the light of further experimental evidence, Spallanzani modified his explanation to one based on hearing. Although this view was ultimately proven to be correct, it was rejected and the touch theory was retained. The subject was abandoned; it was only in the mid twentieth century that serious research was done in the subject, principally by Griffin and Pye. More complete investigations have shown that the bat is fully equipped with an animal sonar system; there are many detailed variations as the technique is used by the suborder microchiptera, which contains over 800 species. Emission of the signals is from the larynx at 10–200 pulses per second (pps). A low rate of 10 pps is used far from the target to ensure good resolution and the rate increases to 200 pps close to the target. The duration (0.2–100 ms) and intensity (50–120 dB) are decreased when nearing the target to avoid receiver saturation and temporary deafness. The pulse interval is linked to the desired range (100 ms allows 17 m range, while 5 ms gives a range of 85 cm). Directionality is assured in the usual way by reception with the two ears of the bat. A number of studies have shown that the bat has an incredibly sophisticated signal processing system. There are two main modes of operation: (1) Frequency modulation (FM) sweep, which permits very precise localization by short duration signals. It is effective for close-in work and where there are numerous targets, as it affords a resolution as good as 1 mm. It allows the use of cross-correlation techniques by the bat. The disadvantage is the reduced range due to the use of many frequencies, meaning a lower signal level per frequency; and (2) Constant frequency (CF), which allows the use of Doppler shifting. It is best adapted to a stationary bat in an open environment. Long-range detection is possible due to the concentration of energy at one frequency. Harmonics can also be used and these are also exploited for Doppler. The bat’s auditory system is, of course, highly developed to handle this sophisticated signal processing. MRI studies have shown that FM and CF modes involve different parts of the bat’s brain [2]. In some cases, the physiological system is very specialized for the technique used; the mustached bat has a thickened membrane to optimize reception at 61–61.5 kHz, precisely the Doppler-shifted second harmonic frequency. In summary, there is evidence that the bat’s echolocation system is almost perfectly optimized; small bats are able to fly at full speed through wire grid structures that are only slightly larger than their wingspans. Good discussions of echolocation by bats are given in Suga [2] and Fenton [3].

It is also fascinating that one of the bat’s main prey, the moth, is also fully equipped ultrasonically. The moth can detect the presence of a bat at great distances—up to 100 ft—by detecting the ultrasonic signal emitted by the bat. Laboratory tests have shown that the moth then carries out a series of evasive maneuvers and sends out an ultrasonic signal consisting of a series of clicks. For a long time, the precise role of these clicks was uncertain, but recent controlled laboratory experiments with tethered tiger moths have shown unambiguously that the clicks represent a jamming signal to be picked up by the bat [4]! Another fascinating example is the praying mantis. It has a single ear with which it detects the approaching bat. Just before the bat arrives, it goes into a steep dive, just like a fighter pilot engaged in a dog fight [5]. Finally, another example of ultrasonics used by insects is provided by the cricket meconematinae katydid in the South American rain forest [6]. Most crickets produce sound by flipping their wings, but this katydid produces the highest frequency of all insects by another method. He has a scraper and uses it to close the forewings to store elastic energy. At some point, the scraper slips free and the elastic energy is released in the form of a short ultrasonic pulse. Crickets have another specialty in that the female has an incredibly high directional sensitivity that cannot be explained by the intensity difference received by the two ears. It turns out that the female is sensitive to the phase difference, an effect which is optimized if the male sends out a long pure tone.

Several types of birds use ultrasonics for echolocation, and, of course, acoustic communication between birds is highly developed. Of the major animals, the dog is the only one to use ultrasonics. Dogs are able to detect ultrasonic signals that are inaudible to humans, which is the basis of the silent dog whistle. However, dogs do not need ultrasonics for echolocation, as these functions are fully covered by their excellent sight and sense of smell for long- and short-range detection. Other examples of terrestrial animals using ultrasonics are rodents, chiefly Richardson’s ground squirrel, the prairie gopher. These rodents live in colonies and use ultrasonic alarms to warn other members of the presence of predators. They use both audio (8 kHz) and ultrasonic (48 kHz) alarms, depending on the distance of the predator.

Anyone who lives in the country knows that singing is a vital part of a frog’s life. Amphibians play a link role between land and aquatic life, and this is also true for animal’s use of ultrasonics. The Chinese concave-eared torrent frog, Odorrana Tormata, is a very interesting example of a creature’s adaptation to its environment. It has been studied in detail by Feng and Narins over the last 10 years [7] and the findings are fascinating. These frogs live near noisy streams, leading to a high ambient noisy background, which was found to cover virtually the full audio spectrum. The frogs get around this by making their calls in the ultrasonic range, producing intense chirps up to 128 kHz. They use all the tricks developed independently by bats: CF and FM calls, period doubling, and sub-harmonics, indicative of nonlinear chaotic behavior. Their recessed eardrums and shortened connecting bones and other physiological aspects allow them to hear up in the ultrasonic range. Most surprisingly, they have active control of the opening to their Eustachian tubes, allowing them to close the tubes when necessary to cut down the background noise to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Like the katydid crickets, both males and females display an extraordinar...