![]() Part I

Part I

Ideas and structures of the book![]()

1

Economics in an interdisciplinary context

Humans are heterogeneous in many ways. Nothing can be more evident than this simple fact. Yet, in mainstream economics, the device of the homogeneous agent or, more formally, the representative agent, has been employed for quite a long, yet uneasy, period of time. Psychologists, on the other hand, have acknowledged the heterogeneity of agents right from the beginning. Various developments in psychometric testing simply show us that humans are empirically different. They are not just bounded rational; they are heterogeneous in cognitive capacity as well as personality. Moreover, anthropologists and sociologists show us that, when put in a social context, they are under different sets of beliefs or norms. From the viewpoint of genetic biology, some human heterogeneities are inherited from parents or ancestors. Nevertheless, mainstream economics has long been silent on all of these human factors, assuming that they are not economically sensible. The empirical evidence accumulated in recent years, however, shows the significance of cognitive capacity, personality, emotion, cultural inheritance, and social norms, from micro to macro. Nevertheless, the modeling techniques which can incorporate agents who are heterogeneous in these dimensions and demonstrate the emergent aggregate behavior through their interactions are less well established in economics.

The purpose of this book is to place the study of economics in an interdisciplinary framework so that the underlying mathematical or computational modeling can be grounded in various kinds of empirical evidence ranging from genetic biology to neural sciences, sociology, psychology, and, of course, experimental economics. In fact, this interdisciplinary modeling has already existed by different names among people with different backgrounds. For people with a conventional economics, psychology, or mathematics background, its familiar name is behavioral economics; for people with a mixed background of economics and computer sciences or computer engineering, its familiar name is agent-based computational economics; for the recent immigrants from physics to their “colony” in economics, it is called econophysics. Each of its names represents an origin of its development. Behavioral and econophysic modeling is more analytically demanding, whereas agent-based computational economic modeling is computationally intensive.

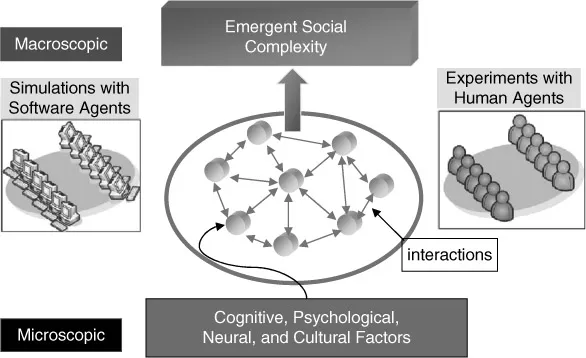

Regardless of different names, models with these tags and origins share a great common feature, i.e., they can each replace the conventional representative agent model and provide an alternative microfoundation. Figure 1.1 shows this common feature. We will come back to this figure and elaborate on its essence in Section 1.1. Here, we only provide a brief list to exemplify the microfoundational work already done in each of the three research areas.

Figure 1.1 Microfoundations and macroeconomics.

Behavioral macroeconomics

There is a series of works on behavioral macroeconomics by George Akerlof, the 2001 Nobel Laureate in Economics. The most notable features of this are his Nobel Prize lecture (Akerlof, 2002), his American Economic Association Presidential address (Akerlof, 2007), and his advice on the current financial tsunami (Akerlof and Shiller, 2009). This series can be augmented by a number of macroeconomic laboratory experiments (Duffy, 2009).

Agent-based computational economics

Agent-based computational economics, almost since its beginning, has been devoted to the study of macroeconomic issues. Leigh Tesfatsion, on her Iowa State University web page, http://www.econ.iastate.edu/tesfatsi/amulmark.htm, has a collection of these studies. Among them, Chen (2003), Delli Gatti et al. (2008), LeBaron and Tesfatsion (2008), and Delli Gatti et al. (2011) provide various illustrations with different motives. Due to the financial crisis which occurred in 2008–2009, attention has been paid to agent-based computational economic modeling as an alternative approach to maintaining better tabs on the increasingly complex and intertwined economy (Buchanan, 2009; Farmer and Foley, 2009). In addition, a series of conferences were organized in the year 2010 to reflect on the crises in economic theory with regard to the economic crisis of 2007–2009. In 2009, George Soros pledged to give 50 million dollars over ten years to set up the Institute of New Economic Thinking as a reaction to his feeling that “false theory” has resulted in tremendous damage to the world economy. Agent-based economic modeling is considered to be a candidate for an alternative.

Econophysics

In physics, during the late nineteenth century a fundamentally new approach referred to as statistical mechanics was advanced by James Maxwell (1831–1879), Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906), Josiah Gibbs (1839–1903), and others. This approach, which significantly contributed to the study of molecular dynamics, was also formally introduced to the study of economics and even the social sciences in the 1990s.1 This new field is broadly known as econophysics or sociophysics.2 An econophysics approach to macroeconomics can be exemplified by a series of work done by Masano Aoki (Aoki, 1996, 2002a; Aoki and Yoshikawa, 2006).

1.1 The interdisciplinary framework

Figure 1.1 has all the ideas to be included in this book, albeit expressed in a highly simplified way. Let us start with the middle part of the figure, which intends to picture a system of interacting agents.3 For a physicist, this picture may be read as a particle system, with two important departures:

Heterogeneous agents

First, agents (particles) are not homogeneous; instead, they are heterogeneous. Abandoning the device of the representative agent is exactly the concept conveyed at the beginning of this book. In Part VI, we will provide corroborative evidence and discussions as to why heterogeneous agents should not be viewed as an exception but as a rule in the future of economic modeling.

Interactions

Second, the relations among the agents (particles) are not just random bumping but social in the sense that these agents mutually influence each other, so that their behaviors change along with these interaction processes. These agents are, in general, not independent. This feature allows us to accommodate concerns from anthropology, religion, culture, sociobiology, and evolutionary psychology.

Social networks

Although the interactions among agents can be erratic, they may not be entirely random. Implicitly or explicitly, the interactions take place through social networks. The topologies of social networks can be another crucial factor for the interactions, and the topologies, in general, are endogenously determined.

Homo sapiens

Let us move to the bottom of Figure 1.1, which describes these individual agents. In conventional economics, the description of the agents is simple: Homo economicus or economic man. They are identically infinitely smart, hyperrational, self-interested, unemotional, and utility-maximizing agents. While these creature have been surviving in mainstream economics for decades, economists are now becoming more interested in knowing Homo sapiens—emotional beings (Thaler, 2000).4 This broader interest has brought about significant growth in interdisciplinary engagement between economists and other social scientists or even scientists. Psychology and computer science both come into play from this side.

Psychological fundamentals

On the one hand, we certainly hope to give a more realistic description of the human agents by at least not missing their essential dimensions; on the other hand, we want to make this description programmable. The former motivates an increasing number of economists to learn from psychologists and coherently ties economics and psychology in an unprecedented way. This interdisciplinary collaboration between the two has also promoted a new subfamily in economics, namely behavioral economics. Economists are now more alert to the social consequences of widely documented agents’ behavioral biases. More recently, psychology has helped economists to reshape a proper definition or representation of an individual economic agent. A series of recent studies indicates that cognitive capacity (the intelligence quotient) and personality are two important missing elements in conventional characterizations of economic agents. In fact, these two human factors should be thought of as the fundamentals of the economy; they are certainly more concrete than preference, a very controversial idea, both historically and currently.

Artificial agents

We program the artificial agents to reflect various kinds of psychological fundamentals, behavioral rules, or behavioral biases. Artificial agents is not a term commonly used in behavioral economics, although all the models inevitably start with some artificial agents. The whole of Part III is devoted to this construct, but most materials introduced there were produced in the earlier stages of agent-based computational economics when it was still distinct from behavioral economics. In agent-based computational economics the focus of artificial agents is on learning, whereas in behavioral economics the focus is on preference and utility. In the future, the gap between the two will be narrowed as behavioral agent-based computational economic models are gradually developed. Chapter 19 presents one case in point.5

1.2 Organization of the book

Normally, the table of contents of a book suggests that the reader can read the book in a sequential order. While the table of contents must be unique, that kind of suggestion is not. Therefore, in this section, we elaborate on the organization of the book and suggest some alternative tables of contents which could be used by different readers with different purposes or different pursuits.

1.2.1 Two fundamental questions

The book tries to answer two questions which we consider to be quite fundamental to the study of agent-based economic models, namely, what and why? What is agent-based computational economics? Why do we need agent-based economic modeling of the economy? These two questions are generally shared by other social scientists who are also interested in agent-based modeling. Therefore, they are better addressed in a broader background, i.e., agent-based computational social sciences. To answer the first question, it would be nice if we could start with some very simple agent-based social or economic models which, however, all have the essences of agent-based models. Chapter 4 serves this purpose. It is mainly composed of the three simplest agent-based social models, namely Schelling’s Segregation Model, Conway’s Game of Life, and Wolfram’s Edge of Chaos. This chapter can help beginners to quickly grasp what an agent-based social model is.

The most direct way to address the second question is to ask whether we can have a collection of successful agent-based models in the social sciences. By success, we mean that these models are capable of explaining or predicting some social phenomena which are hard to capture using the conventional models of the respective disciplines or are able to provide new insights. While we cannot be absolutely sure what these models are, Chapter 2 does make such an attempt. In addition to that, Epstein (2008) provides a long list of answers to the issues involved, and in Chapter 2 we shall review some of them.

1.2.2 Novelty discovery: toward autonomous agents

The book will start with a concrete example of agent-based (economic) modeling, namely cellular automata (Chapter 4). The reason we choose cellular automata as our kick-off example is partially because we consider a model of agents to be the first part of agent-based modeling. However, to clearly indicate our departure from Homo economicus to Homo sapiens, we would like to provide a simple historical background on the development of economic agents in economics; specifically, from algorithmic (behavioral) agents to autonomous agents (Chapter 5). This will quickly lead us to see that part of the economic agents is defined by the associated algorithms. In fact, Chapters 5 to 7 provide many more illustrations on the algorithmic aspects of economic agents, as they are called algorithmic agents.

Autonomous agents are first exemplified in Chapter 6 via an artificial intelligence tool called genetic programming (GP), while the foundation work for autonomous agents is not given until later in Part IV. This line of exposition is then further extended to Chapter 8. Chapter 8 can be read together with Section 14.5 and Part VIII, and are all concerned with a central theme of the book, which I shall refer to as the legacy of Marshall. Together they demonstrate one unique feature of agent-based modeling, i.e., its capability of modeling intrinsically constant changes. One essential ingredient of triggering constant change is equipping agents with a novelty-discovering or chance-discovering capability so that they may constantly exploit the surrounding environment, which causes the surrounding environment to act or react, and hence change constantly.

1.2.3 Microstructure dynamics

If economics is about constant change, and that happens because autonomous agents keep on searching for chance and novelties, then change in each individual and change in the microstructures must accompany the holistic picture of constant change. A number of chapters in this book attempt to have microstructure dynamics as their focus. Part V illustrates the rich microstructure dynamics in agent-based financial markets. Chapter 14 is mainly devoted to the study of microstructure dynamics in light of the statist...