![]() Part I

Part I

Comparative and theoretical issues![]()

1

South Asian migration to the GCC countries

Emerging trends and challenges1

Ginu Zacharia Oommen

South Asia’s long historical and cultural links with the Gulf date back to ancient times when West Asian ports were a key element in maritime trade. The discovery of oil and the economic rise of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries attracted a huge influx of migrant workers from South Asian countries, particularly India, to the Gulf. At present, out of 15 million expatriates in the Gulf region, South Asians constitute around 9.5 million (Ozaki 2012). Of these, Indians are the largest group. The historical linkages, colonial domination, religious and cultural proximity, poverty, unemployment, political instability and insurgency in the South Asian countries are some of the factors that have led to this large influx to GCC countries. Kapiszewski (2006) argues that in the international milieu, West Asia has always been a major destination for labour migration, particularly the GCC countries. In Gulf countries, migrants constitute one-third of the total population.

In the 19th century, the British administration recruited skilled workers from the Indian subcontinent to the Gulf region in clerical and secretarial positions for the smooth functioning of the colonial administration (Jain 2006). Later, with the development of the oil industry, it created an additional need for workers in clerical jobs as well as skilled and semi-skilled manual occupations. As the local labour of the region was scarce, or had limited experience in industrial employment, oil companies were obliged to import large numbers of foreign workers in these categories. The South Asia region, especially India, receives the largest amount of remittances, particularly from the Gulf. Remittances from GCC countries form the major external financial flow for these countries. Seccombe and Lawless (1986) noted that the British administration promoted the migration of Indian workers to the newly established oil fields and they also blocked the inflow of Arab workers from the neighbouring Arab countries.

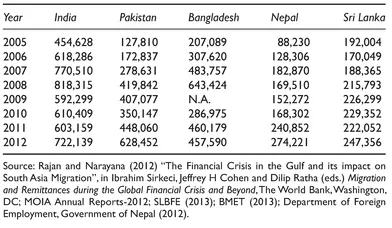

The strategic and economic implications of ‘Asianisation’ in terms of migration and remittance flow is quite important for both the sending and receiving countries, as India alone received US$23 billion in 2012 from the GCC region (Ozaki 2012). The South Asian community has made a remarkable contribution to the socio-economic progress and cultural development of the GCC countries. Interestingly, the ‘Asianisation’ of migrant labour in the Gulf is the outcome of the ‘preference and choice’ of the receiving governments due to various economic-political considerations. Though the composition of migrant workers has been shifting in GCC countries, a consistent and significant shift from Arab workers to Asians workers has taken place, ever since the late 1970s, mainly to safeguard the political interests of the oil-rich monarchies (Kapiszewski 2006). The initial domination of Arab workers from the neighbouring non-GCC countries started to decline in the mid-1970s, while, on the other hand, the inflow of South Asian workers increased significantly, which defended both the strategic and economic interests of the Gulf region. Moreover, the Asian migrant workers are considered to be relatively less expensive, diligent, submissive, and least interested in local politics. The flow of migrant workers from Asia, particularly South Asia, had given stiff competition to workers from West Asia (Silva and Naufal 2012). In the last three decades, GCC countries have massively recruited maximum workers from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal (Kapiszewski 2006). Thus the South Asian community has become the dominant workforce in the economy of the region. Table 1.1 indicates the unparalleled flow of South Asian migrant workers to the GCC region, from 1,069,761 in 2005 to 1,530,222 in 2008.

Surprisingly, the global economic crisis, job cuts, Arabisation policies of the GCC governments, and socio-spatial isolation of the expatriates has not reduced the steady flow of migrants from the Asian region, nor has it created a ‘reverse migration’ back to the sending countries. Irudaya Rajan, in “The Financial Crisis in the Gulf and its Impact on South Asian Migration and Remittances” notes that only 5 per cent of the migrant labourers returned to South Asia during the economic crisis (Rajan and Narayana 2012). The GCC government’s frequent appeal for the ‘localisation of jobs’ has not been fully implemented by the workforce due to the non-availability of a well-qualified workforce from the native population.

Table 1.1 Outflow of migrant workers from South Asia to the Gulf, 2005-09

The recent decision of the Saudi Arabian government to strictly implement Nitaqat or the nationalisation of the workforce could be an unexpected setback in the free flow of migration to the Gulf region (The Hindu 2013). The majority of expatriate workers in GCC countries are largely from South Asian countries. In 2009, the share of Asians in the workforce in Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) was around 80 per cent, while Asians constituted 60 per cent of the workforce in Saudi Arabia (Migration News 2012). The global financial crisis partially affected migrant workers as the GCC countries had high reserves accumulated which they had earned during the oil price hike and they invested this capital in infrastructure projects during this period. Thus reverse migration to the South Asian region was less (Rajan and Narayana 2012). Moreover, the local population is facing either a skill-mismatch in the job market or the current educational system in the Gulf region is inadequate to produce an efficient and skilful workforce.

This chapter explores new trends in the ‘South Asia-Gulf migration industry’. This particular aspect has not been given much attention in the relevant literature, despite the emergence of the ‘South Asia-Gulf Corridor’ as an important epicentre of transnational migration with greater opportunities, prospects and challenges.

Migration history and trends

Part I

Trade relations between the Indian subcontinent and the Arab region as the West Asian was very strong, and ports were the epicentre of Indo-Mediterranean trade (Jain 2006). However, the historical contributions of the Semitic communities in the Indo-Mediterranean trade, cultural and religious interface have not figured prominently in South Asian studies. Jain, in his studies on the Indian Merchant communities, highlights the presence of vibrant Indian merchant communities in the Persian Gulf towns during the British Raj (ibid.). India’s trade in the Mediterranean region was fostered by the presence of Indian business settlements across the Persian Gulf. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Indian merchant community had a significant role in the internal trade of Oman and the UAE (Allen 1981). In 1929, Indian goods constituted 72.47 per cent of the total imports of Bahrain (Fuccaro 2009). However, with the independence of the Gulf countries, the influence of the Indian merchant communities started receding in favour of native trading communities. The skilled Indian workers played a key role in running the colonial administration in the GCC region and Indians were the ‘preferred’ workforce of the British (Seccombe and Lawless 1986). In the post-Second World War period, a large number of Indians were recruited in postal services, communications, police, and in various colonial administrative sectors (Jain 2006).

Seccombe and Lawless point out that in 1939, Indians accounted for nearly 94.3 per cent of the total clerical and technical employees and 91.1 per cent of the total artisans employed in Bahrain Petroleum Company, a leading oil company (ibid.). By 1950, the large oil companies in the Gulf employed nearly 8,000 immigrants from the Indian subcontinent (Claude 1999). A majority of these migrants are reportedly known to have originated in Kerala and other south Indian provinces. Most of them – even the highly educated professionals – are on contract and, therefore, are not allowed to settle permanently in these countries. Later, the large-scale extraction of oil and the subsequent economic rise of the GCC countries in the late 1960s inspired a huge flow of migrant workers from India to the Gulf region. Thus, in 1970–71, there were only 50,000 Indians in the region. This figure rose to 150,000 in 1975 and 1.5 million in 1991 (Natarajan 2013). Presently, the Indian population in the Gulf region is estimated at about 5.5 million (MOIA 2012). Indian communities in the Gulf countries predominantly consist of skilled, low-skilled and semi-skilled workers; technical, supervisory and managerial personnel; professionals and sub-professionals; and entrepreneurs/businesspersons.

The state of Kerala continues to be the largest migrant-sending state, followed by Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar (Rajan and Zacharia 2012). Out of a total 6 million migrant workers who migrated internationally during 2000–10, 85 per cent joined the workforce of the oil-rich countries in the Persian Gulf (Ozaki 2012). While the construction boom of the 1970s led to the employment migration to the Gulf countries, globalisation and the IT boom of the 1990s have accelerated mutual trade and investment in both regions. Statistics show that the flow of migrant workers from India to the GCC countries was never quite fast in the late 1970s. By the mid-1980s, even this flow had lessened, although by the beginning of the 1990s the flow of migrants had accelerated once again. It declined drastically in the late 1990s, but once again peaked in mid-2000 (Jain 2008). Table 1.2 shows how since 2001 there has been a significant upsurge in t...