1 Introduction

In June 2016, England (population 55 million) lost to Iceland (population 330,000) in the Euro 2016 Football Championship and failed to make it into the quarter-finals of the tournament. I live down the road from the Arsenal Football Club in London, which is an internationally competitive club in England’s Premier League, attracting players, sponsors and resources from around the world. Why is there such a gap between the fortunes of England’s club football and its national team? Why do resources, energy, and ethos coalesce around the enterprises that are premier football clubs in England but cannot do so when it comes to fielding a national team? The answer lies in the history of England’s institutional development of its particular form of capitalism.1

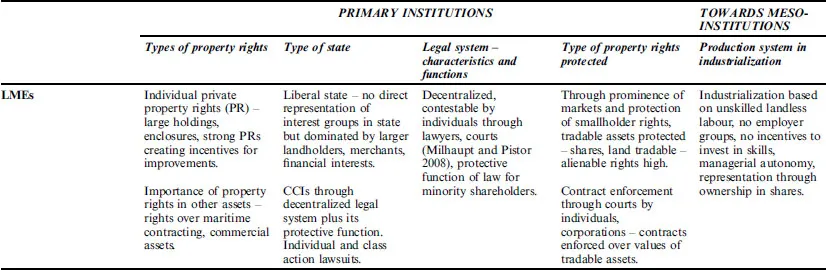

My starting point is to build on the varieties of capitalism literature of Hall and Soskice (2001), which divided developed capitalisms into liberal market economies (LMEs), such as those of Britain and the United States, and coordinated market economies (CMEs), exemplified in the first instance by continental European countries such as Germany and France. These varieties of capitalism have different characteristics in terms of what I call their ‘meso-institutions’ – their labour market institutions of employment protection and mobility of labour, and the types of skills and training these cultivate – and their capital market institutions, such as the degree to which firms use equity markets to finance their activities and the extent to which they are publicly-listed and issue shares that are freely tradable on those markets. LMEs have been characterized as having less employment protection, greater mobility of labour and changing of jobs, and an emphasis on the general and portable skills that people carry with them between different firms. Firms in LMEs use equity markets to raise finance and are publicly-listed on stock markets. There is more shareholding by individuals and institutions, an example of the latter being pension funds that are external to the firms whose shares they hold. There is a more active takeover market, meaning that companies and assets are bought and sold through the market for corporate control. In this process, acquired companies typically have to change strategic direction, destroying skills and assets that had been built up under the previous regime. These assets and skills are not well protected under liberal institutions. Paramount in these economies is using markets to maintain the tradability of assets.

The coordinated market economy has greater employment protection, more coordinated wage bargaining, longer job tenure and greater training in skills relating to specific firms. Firms use close relationships with their banks rather than using public equity markets and public listing of companies. Shareholding structures are more concentrated, with leading owners having blockholdings of shares. Owners keep control of their companies, and there are numerous obstacles in the way of hostile takeovers. These obstacles take the form of concentrated ownership itself, which cannot be bought out; of proxy votes by banks; and of different classes of shares, which enable capital to be raised without lessening owners’ control over their firms. They result in the protection of strategic assets – the skills and assets built up inside companies – rather than an emphasis on the tradable nature of assets and the protection of that tradability.

Making this distinction between the kinds of property rights that are protected is new to the literature. I am building on this in two ways. First, I believe there to be a substantial truth in the distinction between these different ways of running capitalism, and I want to understand how they got to that point, that is, to bring out the histories of their institutions. Second, I would like to forge the connection between the meso-institutions of the varieties of capitalism and the primary institutions that underpin capitalist economies. Neither of these elements has been explored before. When property rights have been discussed, it has been assumed that they are all of one nature or one type. Here, I bring out the differences and tensions that exist between different kinds of property rights: tradable versus strategic, individual versus customary, and privately ordered versus publicly backed by the state.

How I do this is through outlining institutional histories across different countries that have been classed as running their capitalisms in different ways. This book is largely about joining up the dots, bringing together different literatures so as to focus, historically and conceptually, on the linkages between the protection of different kinds of property rights in the different varieties of capitalism and the historical routes and underpinnings that offer an explanation as to how and why they became so different. Of necessity, the joining together is sketchy and schematic – it highlights different building blocks – the different natures of property rights, the contrasts between legal systems and differing conceptions of the rule of law, and the variety of and changing constructions of state apparatuses and structures. These I label primary institutions, the institutions that are deemed to underpin capitalism and enable contract enforcement to occur.

I want to emphasize that we cannot understand the way capitalism works in any country – how its meso-institutions are constructed and operate – without a grasp of how a given country’s primary institutions were constructed and how they evolved. I give a more nuanced view of how each country evolved institutionally and how it arrived at its very different variety of capitalism, but I also bring out the deep-rooted nature of institutional evolution: the centuries-old build-up and incremental change that entrenches ways of doing and seeing things. This in turn brings out the crucial interaction and dynamic between informal structures in a country and the evolution of formal institutions. I am not able to explore this at all adequately, but nevertheless I do want to emphasize the importance of, for example, the individualistic ordering in Britain as it took root from the post-Black-Death 15th century and compare it with the more hierarchical bureaucratic structures that took shape in France and some parts of what would become Germany. And when I come to look at how property rights ‘take’ in developing contexts, I also want to emphasize the importance of the more collectivist group-orderings in Tanzania, of villages and cooperatives, which also have deep roots.

These different informal structures mean that the same size of state by some measure of state expenditure in GDP have given rise to very different degrees of regulation or state intervention or public presence in the economy. States comprising the institutions of government, of administration, and of the judiciary have taken different shapes across countries and have different relationships, types of legal capacity, degrees of centralization or decentralization, and extent of independence of their judiciaries from the state executive. For example in France, state administrations have played a more direct and interventionist role in settling disputes between parties, such as disputes over property rights, whilst in liberal economies state administrations have kept out of such disputes, which have been dealt with through the courts.

I want to suggest the importance of private orderings of maritime property rights, which were significant in the building up of commercial roots in Britain through the chartering of companies, through privateering and letters of marque, and through the symbiotic relationship between the growth of the fiscal capacity of the British state and its naval capacity. This story intersects with the history of landed property rights, which themselves were bound up with the 17th-century shift of power from Crown to Parliament; the strengthening of common law and a decentralized legal system somewhat removed from direct state executive control; and the creation of constraints on executive power through a constitutionally limited government. This contrasts with the continental European states’ administrative systems, which have historically featured more centralized civil codification, stronger state influence over the judicial system, more limited fiscal capacity and yet greater interventionist powers – a set-up which has been variously known as dirigisme or étatisme. Critical to this contrast is the intertwining of financial market development with liberal states’ ability to issue public debt: the priority and ability of Britain and the United States to service public debt from taxation and not default and to honour and protect property rights linked to those markets, a policy which in turn enabled naval expansion, victory in war, commercial extension, and, in the case of the United States, territorial expansion across North America. It raises the questions of why the continental European states did not go down the route of developing fiscal capacity through equivalent financial markets, and whether their étatisme led to more privately-held companies, as has been argued.

Why these countries? I take as my sample countries the two supposedly liberal economies – Britain and the United States – the two leading continental European economies that were originally central to the conception of the coordinated market economy – France and Germany – and two contrasting emergent capitalisms, Tanzania and China. In each coupling, there are similarities and large contrasts to highlight. The United States carried certain institutional orderings over from Britain – common law, the importance of chartered companies and the corporation, and a certain individualism. But it was also constructed institutionally very differently with regard to its separation of powers, its decentralized federal executive, and the role of race and slavery within its domestic economy. France and Germany of course also have different institutional histories. France is known for its highly centralized state apparatus, its prolonged absolutist government, and the importance of its state administrative structures. Germany, on the other hand, was an amalgam of differing states and orderings between the Hanseatic north, the Bavarian Catholic south, the commercial Rhineland states in the west, and the Junker estates in the east. Somehow these were gathered together into one country in the late 19th century. But there are certain institutional similarities, which include the importance of state administration and bureaucracy; centralized legal codifications; and the role of the state in providing education, infrastructure, and skills for industrialization. Tanzania and China in 2016 are widely differing. But in 1980 their per capita GDPs were $601 and $1,061 (in 1990 international Geary-Khamis (GK) dollars), respectively, as Table 1 shows. They were both poor agricultural and socialist nations with legacies of dirigiste authoritarian leaders. Between then and 2010, China’s per capita GDP grew tenfold whilst Tanzania’s increased by 30 per cent. I unpick their institutional histories – their property rights, legal systems, and the nature of their states. I connect these with their meso-institutions of enterprise development: the corporate governance of listed firms in China and the governance of cooperatives and their place in commercial supply chains in Tanzania. This reveals the urban-rural divides that exist in both countries and suggests the institutional underpinnings of Chinese growth and of Tanzanian relative stagnation.

Institutions matter for enterprise development and investment, for their development leads to economic growth and increased wealth. This much has been established by decades of research evaluating the relative importance of institutions, geographical characteristics and trade in stimulating development (North and Thomas 1973; Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi 2004; Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson 2001; and Robinson 2012). The institutionalist camp argues that institutions trump geography and trade as a meta-explanation for development, contra others such as Diamond (1997) or Findlay and O’Rourke (2007), who argue for the supreme importance of geographical characteristics or world trade. The institutionalist argument, crudely paraphrased, goes something like this: if good institutions are not present, economic development does not occur; economic development is correlated with the presence of good institutions. And by good institutions, proponents of this position mean clarity of property rights, good contract enforcement, a functioning legal system independent of interference from the state executive, and an effective state in terms of its having a monopoly over violence (with no competing armies or factions able to challenge it) and sufficient administrative capacity to provide public goods. This set in train the search for a blueprint of ‘good institutions’ with the aim of importing or constructing them such that growth will follow.

Table 1.1

Sources and units. Per capita GDP in 1990 international Geary-Khamis (GK) dollars. Maddison Project through Clio-Infra Project, Max Roser, https://ourworldindata. org. Database and paper Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden (2013) ‘The First Update of the Maddison Project – Re-Estimating Growth before 1820’. Population: Clio-Infra Data from https://ourworldindata.org/world-population-growth/long-run-historical-perspective-country-trends-in-the-last-500- years. *Population data for 2010 from the World Bank.

But this is much too simplistic. To be fair, this characterization underplays the puzzlement in the literature over how one does attain good quality institutions (Rodrik 2004), which I go into further in the following chapter. But there has been an assumption that clarity of property rights is a relatively straightforward concept, which can be understood and adopted. My argument is that in order to understand how institutions matter, we need a better grasp of the differences between types of property rights, legal systems and states across the different varieties of capitalism. And to do that, we need a better grasp of their histories – of how those institutions of different property rights evolved.

My contribution is twofold: the first thread I entwine is, for each country in my sample – Britain, France and Germany; the United States; and then Tanzania and China – to tie together the historical evolution of their property rights and legal systems alongside the nature of their states. To do this, I need to decompose the idea of property rights. Property rights need protecting, but what type of property rights – which types of assets – need protecting? Whose property rights are protected in each country? And when did this become institutionalized? Linked to property rights are the different natures of legal systems. Legal systems are structured differently across countries and have different functions. In liberal countries, for example, legal systems are more decentralized, more reliant on common law; lawyers are prominent and are numerous and widely used to settle disputes and to challenge existing laws. In other countries, however, administrative structures counterbalance judicial systems, which themselves are more centralized and less accessible. When did these differences crystallize, and how do they link to the nature of the state?

The nature of the state is a large and complex concept. The links that I develop are between state fiscal capacity – the power of the state to raise money through taxation and public debt – and the state’s effective capacity to expand – through wars in terms of territory, commerce and wealth. The liberal states’ capacity to issue public debt was built on their credibility in borrowing and not defaulting. In turn, this arose from the greater protection and priority those states gave to tradable assets in the form of government securities. This was a particular type of coevolution – liberal states honoured promises to finance public debt, which was done out of taxation. This created a low-risk form of asset and contributed to expanding the financial market in those assets. This supported the development of financial institutions, particularly localized financial markets in equities as well as government securities, which were much more pronounced in the LMEs from an early stage. Linked to those markets was the pre-eminence in organizational form of companies and corporations that used those financial markets.

This goes together with ideas about the state – the ideological stance about what states should do, in the economic sphere particularly – and the drawing of different boundaries between private and public spheres. The second thread that I entwine, then, is what is meant by ‘constraints on the state’; a state executive with power reined in in particular ways. I argue that in relation to tradable property rights in particular, the liberal states have been more constrained, and I outline where those constraints came from. I then contrast this with less-constrained state power over property rights in continental Europe and unconstrained states in Tanzania and China. This involves linking the protection of different types of property rights with what North, Wallis and Weingast (2009) call the ‘dominant elites’, their relationship to their states in each country, and the ideologies or stance of those states – how protectionist or mercantilist and how liberal they were and how they evolved to sanction the protection of one type of property rights over another.

These elements of the nature of the state are all inter-related: the dominant elites are typically in charge of courts and judicial-making structures, and they are usually influential in the legislative assemblies; the dominant elites feature in the administrative structures and bureaucracies. But some states – England – allowed much greater autonomy and power to the large landowning elites, gentry and notables in their roles as justices of the peace, in local courts, and in running other local municipal services, schools and hospitals, whereas other states – France – were more centralized from the 17th century and superseded judicial structures by administrative structures that were run by the administrative bureaucracy and largely bypassed the more regional nobility and the seigniorial courts. Prussia and then Germany also did a lot more through the bureaucracy, administrative structures and the centralized state than did Britain or the United States.

These contrasts – between states and the types of elites and their power – link back into the differential protection of types of property rights between states. In particular, the primacy of individualized and tradable property rights was embedded in the maritime economy in England (Paine 2013) and built into individualism in the countryside from the 15th century (Macfarlane 1978); they became entrenched and built on after the civil war in England in the 17th century and carried from England to the United States. The priority given to these tradable property rights was combined with Lockean possessive individualism as the cornerstone of individual rights in those countries, independent of the state, acting as a constraint on the state executive and coming prior to any great extension of the franchise.

One difference between England and the United States has been the role that race has played in their development. I bring out the colonial heritage of the Unite...