![]()

1 Introduction

This transdisciplinary historiographical study offers a narrative of corporeality in modern Iran centered on the transformation of the staged dancing body, its space of performance, and its spectatorial cultural ideology. It analyzes the ways in which dancing bodies have provided evidence for competing representations of modernity, urbanity, and Islam throughout the twentieth century. This book focuses particularly on three theatrical Iranian dance genres (as discourses) which emerged in the twentieth century. These include the “national dance” (raqs-i milli) of the Pahlavi era (1925–79); cabaret dancing of the post-1940 era (onstage and on cinema screens); and the post-revolutionary genre called “rhythmic movements” (harikat-i mawzun).1 Each genre is studied as an artistic product conditioned by multiple social, cultural, political, economic and ideological factors (see Figures 1.1–1.3).

Exploring the socio-historical milieu of performance, this book investigates the (contending) discursive constructions of the dancing body and its audience. At the same time, it historicizes the formation of dominant cultural categories of “modern,” “high,” and “artistic” in Iran and the subsequent “othering” of cultural realms that were discursively peripheralized from the “national” stage. This is enhanced by close analysis of the three contending modern vernacular social discourses: (1) the national(ist) discourse, which was aimed at educating the nation and achieving national arts, (2) the anti-obscenity discourse of the press with religious orientations, which I will refer to as Islamic discourse, and (3) the Marxist-inspired discourse of performing arts and mainly the theater. All of these discourses intersected in reacting to the intrusion of female sexuality into public space and the emergence and commercialization of mixed gender forms and sites of urban popular entertainment. Within this analysis is a parallel discussion throughout the book on the historicization of the ways notions of “degeneration” (ibtizal) and “eroticism” (shahvat) have been constructed, reconfigured, and deployed in the twentieth-century context as moral and aesthetic criteria applied to the performing body.

This book further explores the ideological applications of the cultural categories for conditioning the aesthetics and ethics of the dancing body onstage, as well as the audience’s taste. This includes the impetuses behind the selection of cultural motifs from ancient symbolism, literature, folklore, and mysticism and religious rituals, as well as the use of European art forms in the construction of new virtuous “national(ist)” or “Islamic” performing bodies. Other factors that I consider in this study include the shifting dynamics of the body in public space as they relate to urban transformations, the state’s top-down implementations in establishing various institutions, the competing conceptions of discipline and regulatory systems as pertaining to public space, and the bio-economy of the dancing body in relation to the income of the performance venues.

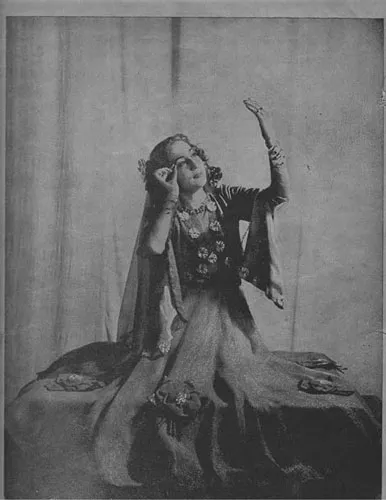

Figure 1.1 A national dancer in the late 1940s

The studio for the revival of classical arts of Iran, souvenir program, undated.

Figure 1.2 A Cabaret dancer; Rawshanak Sadr in Jahil va Raqqasah (The Jahil and the dancer, 1976)

Ida Meftahi’s Personal Archive.

Figure 1.3 Rythmic Movements, Farzanah Kabuli in Epic of the Rock Revolution, 2000

Photo by Omid Salehi.

According to the socio-historical context of performance, the onstage performer in each genre has constituted a differing dancing self through choice of movement, posture, appearance, and behavior, as well as gender performativity and relations. Therefore, this project required multi-method data gathering and analysis from both pre- and post-revolutionary eras. The types of data used for this study encompassed textual, narrative, visual, and that based on participant observation (conducted in dance classes, rehearsals, and performances), all of which complemented different aspects of each other.

Discourse analysis on dance, the performing arts, and popular culture was conducted through usage of a diverse range of twentieth-century periodicals with various ideological stances, literature pertaining to theater, music, and cinema, as well as governmental documents and program notes. Additionally, academic literature pertaining to music, theater, cinema, and popular culture was consulted. Furthermore, a large pool of cinematic productions was studied for narrative analysis.

I extracted vital information about the work conditions of cabaret dancers of the Pahlavi era from interviews I held with the performers who worked in such settings.2 My examination of the post-revolutionary period also involved interviews with practitioners who have been constantly redefining and re-creating their genres to work around the unwritten regulations of the post-revolutionary stage enforced by theater authorities whose disciplinary gaze (not to discount the other senses) has sought to prevent sexual stimulation and immoral thoughts in the audiences.

The visual data deployed for this study included images of dance, video footage of theatrical performances, and cinematic productions. To interpret the visual data of performance, I focused on visual codes and elements such as theme, costume, posture, gesture, movement vocabulary, pace, use of space, lighting, props, and music to develop a framework of criteria that could explain the semiotics and aesthetics of the staged body in multiple milieus of performance. In examining the dancing body onstage, in addition to movement and semiotic analysis and representational study, I also draw on the recent scholarship on affect, feeling, and emotion, to further explore the sensorial experience of performers and audiences.3 This multi-faceted approach not only deepened my historical study of the body, movement, and embodiments of “vice” and “virtue” in the Iranian socio-cultural context; it also helped to shed light on the regulatory mechanism of the post-revolutionary stage, one which scrutinizes the semiotics of bodies as well as their “feeling technology.”

This study raises a number of theoretical, historiographical, and choreographical issues concerning dance, the body, subjectivity, and biopolitics, and their interplay with nationalism in Iran. Focusing on the female body on the theatrical stage, I draw on several Foucauldian notions including biopower, biopolitics, the effects of the correctional gaze, and technologies of the self.4 In light of Joan W. Scott’s emphasis on the significance of gender as a category for historical analysis, as well as Judith Butler’s gender performativity as a regulatory regime, I explore the various ways in which gender identity is constructed on the Iranian theatrical stage.5 Informed by feminist and post-modernist subject, agency and self, I reconstruct the Islamic concept of self in an effort to explain the transformation of dance in twentieth-century Iran. I explore the genres of national dance and rhythmic movements as “invented traditions,” deployed to promote two competing conceptions of Iran as a modern nation.6 In my analysis of the cabaret dancer on stage and in film, I employ Erving Goffman’s conceptions of “front-stage” and “offstage” to analyze the ways the characteristics of “corruption” and “sexual perversion” associated with the cabaret dancer’s daily life were transformed into a bold performance of sexuality, signified by her costume, movements, behavior, and relationship with her audience.7 Furthermore, in unpacking the corporeal aspects of “degeneration” (ibtizal) and “eroticism” (shahvat) as aesthetic criteria applied to performing bodies, I deploy the notion and theories of affect to explore the emotional impact and the visceral and sensory experience of the audience.

In the area of dance and performance, I rely on pertinent scholarship to explore the significance of the staged performing body, and its potential capacity to project ideologies and constructed identities, ideal bodies, and relations through its appearance, actions, and aesthetics, as well as its interaction with the audience.8 Theories articulating gender identity on stage are of particular importance with regard to the dancing body on the Iranian stage, especially in the area of the ways in which gender, as a visual marker in a theatrical context, is being constructed and often used for cultural conditioning and reinforcing the status quo.9

Conducting the first historiographical study on dance in Iran, I dealt with a number of predicaments throughout this project, forcing me to both broaden the scope of my research and deal with unpredicted but fundamental questions in the area of cultural studies in Iran. A primary problem was a lack of documents on the subject as well as the understudied status of dance and other forms of performance that involved the dancing body. These prevented a more precise periodization of the genres and trends explored in the ninety-year span this book covers.

As I show throughout this study, as a consequence of diverging political attitudes towards modernity, cultural evaluation, and moralization, as well as concerns with sexuality, the historical narratives of performance, even those provided by the secondary literature, have been intertwined with rumors, myths, and speculations. Furthermore, the discursive bifurcation of culture as “high,” “elite,” “modern,” “literate,” “intellectual,” and even “secular,”—as opposed to the “popular,” “low,” “traditionalist” (“unmodern” or “ante-modern”), “illiterate,” “degenerate,” and “religious,”—has been deeply embedded in the socio-political discourses. The uncritical treatments of these notions in the academic narratives further added to the challenges I encountered in this inquiry.

Furthermore, the oral, improvisational, and liminal nature of the forms of performance prevalent in popular realms and their associations with social corruption and prostitution, have resulted in their neglect and dismissal by scholars as immoral and thus unworthy.10 This was especially the case with regards to the interconnected spheres of urban popular culture of the Pahlavi era, including the mutribi scene, the café and cabaret milieus, the theatrical setting of Lalehzar post-1950, and the commercial cinema genre film-i farsi. Constituting a “negative space” in Iranian cultural history, these cultural realms have not only been regarded negatively, but have also been actively kept absent from Iranian historiography, resulting in their systematic omission from historical accounts. In particular, the cabaret dancer has served as a “stop sign” at which scholars have cut off their inquiries rather than entering into the “emotive” realm of her performance. Likewise, the dominance of these cultural categories and the inaccessibility of the performers associated with these realms to the written discourse have made them silent subjects in historical narratives.

A historical overview of the major performances and performance spheres

This section aims to contextualize the performances discussed in relation to the dance genres explored in the book. It first introduces a number of performances that have been categorized as folk, ritualistic, and/or traditional and have been presumed to have existed prior to the twentieth century. Then it moves on to explor...