1 Seeing Design in Art

Visions of Denman Waldo Ross

Denman Waldo Ross (1853–1935), a painter and a prominent art collector in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Boston, was among the few to start a tradition of foundational design education in America at the time. Ross taught design in the Architecture and Fine Arts Departments of Harvard University between the years 1899 and 1935, mostly in the summers. He had previously made his name as a painter, taking classes from disciples of the influential John Ruskin. His watercolor patterns earned him recognition in the American Arts and Crafts Movement. Nevertheless, his art is not published, exhibited, or discussed as widely as are his theories on design principles and teaching, culminating in works entitled Illustrations of Balance and Rhythm (Ross et al., 1900), Design as Science (Ross, 1901), A Theory of Pure Design (Ross, 1907), and On Drawing and Painting (Ross, 1912). Ross’s considerable contribution to the field has been through his approach to teaching art and design.

The pedagogical legacy of Denman W. Ross has mostly survived through his students who either continued teaching at higher education institutions, as Arthur Pope did at Harvard, or turned, as did Georgie O’Keefe, to practicing modern art. Art historians Marianne W. Martin (1980), Mary Ann Stankiewicz (1988), and Marie Frank (2004, 2008a, 2008b, 2011) have been among the small number of scholars who paid due attention to Ross’s legacy and revealed his design theory within the context of history of art and design education in North America. Unlike these valuable historical investigations, this chapter focuses on Ross’s teaching techniques and general pedagogical approach in the context of design education and on establishing a link from 1900 to today. It is not the desire here to provide the reader with historical details on either a century-old pedagogue or on the Zeitgeist that he was a part of. Rather, this text aims to delineate the relevance of his teaching, craft, and theory for contemporary education in design thinking.

Ross had a unique perspective into the teaching of art. He read art critics and historians such as James Jackson Jarves, John Ruskin, and Charles Eliot Norton, he inclined towards viewing art as a product of the mind and not just through its appeal to the senses (Frank, 2008a, 74–75). This intellectual backdrop shaped an interest in Ross towards the means, the how-to, and eventually a theory of design for the arts. His positioning of the term design in front of the term art in a theory about methods is not trivial. The notions of art and design were entwined in the art education scene of the final quarter of the nineteenth century (Jaffee, 2005). As signaled in coincident discussions that took place at the time on the social role of the artist and how the character of artists is generally perceived by society (Singerman, 1999), there was a desire to redefine the terms and practice of art. Ross distinguished between the two terms and reverted to the use of the word Design, rather than Art. His motivation was possibly to emphasize that design, an element in art, can be taught. Ross stated his advocacy of the means to art, rather than what it was, in the context of art education, by claiming: “The purpose of what is called art-teaching should be the production, not of objects, but of faculties, – the faculties which being exercised will produce objects of Art, naturally, inevitably” (Ross, 1907, 193). His magnum opus, A Theory of Pure Design and other texts served as the answer to what those faculties might be.

In most of his lectures and writings, Ross focused on elements that make up shapes such as dots, lines, outlines of planar shapes, and color as well as the principles of balance, harmony, and rhythm. The latter group of terms resonated with the recent theories in Gestalt psychology and principles of perception at the time. Ross used these terms to deliver a method that emphasized compositional skills and knowledge. As he introduced balance, rhythm and harmony as modes of order to lay foundations for art, his motto as instructor was “We aim at Order and hope for Beauty” (Ross, 1903, 358). Order was a foundation for art which the individual would be able to later perform if the foundations were laid correctly.

In examples that neglected any stylistic association, Ross referred to arrangements of nonrepresentational forms constructed of dots, lines, and colors as pure design. The phrase “pure design,” as Ross uses it, is similar to what is generally understood today in abstract design, basic design, or thematic composition. Ross assigned a utility to nonrepresentational abstract form not out of his interest in modern art but due to his attention to conveying practical knowledge about the how-to of design to his students. Although Frank (2008a, 75) points out that the “pure” in the phrase “pure design” may have been a choice influenced by Jarves who used it to refer to a quality in art lost to “anatomical dexterity” starting with sixteenth-century Tuscan painters, it may be more directly linked to the “abstract beauty of line and color” that Jarves (1861, 26) mentions while listing pure design under Choice, a point of technical merit in addition to Composition.

According to Ross, design was the epitome of the means to art. All the elements of design that he depicted brought art closer to science too. That Ross (1901) at the same time vocalized his thoughts on design being a science is significant, as evidence that art, at the turn of the century, had changed in meaning for some. Ross became interested in the process of how art came about, its principles and its controlled body of knowledge. Design was the term to embody the nub of all this. Frank (2008) reports that there is no evidence to tell us of Ross’s personal interest in the developments of science such as the introduction of non-Euclidean geometries or even the theory of evolution. Both developments are often referred to in reading the avant-garde European art in the early half of the twentieth century. Ross was conservative in many aspects of his artist persona but because he was a pragmatist at heart, he was persistent about methodology in art and its teaching. This was his reformative side. Ross’s interest in science was conventional. He took science to be a positivist methodology of rationalization that one can apply to design. Nonetheless, he was a part of the Zeitgeist surrounding the said developments in science and, as shown in Chapter 4, in that Zeitgeist, he had some direct interest at least in the developments in psychology which were important to the arts just as much as, if not more than, those in physics and mathematics.

1.1 Wallpaper Patterns: From Ornaments to Design

Denman W. Ross was the Professor of Design Theory at Harvard University until 1935, prior to the arrival of Walter Gropius in the USA in 1937, and of International Modernism. While endorsing a then revolutionary idea of “design as a science” in his writings, Ross was introducing a fresh approach to design education that primarily targeted the imposing aesthetic structures and timeless formalisms dominant in the field at the time. He was opposed to mindless design that followed canons. He sought instead a modern methodology to replace the traditional styles in teaching design. Although they were acquaintances who seldom worked together, he and one other visionary educator, Arthur Wesley Dow, collaboratively promoted in 1901 what Ross called “pure design” as an introductory curriculum in architectural education. Ross and Dow (1901) wrote: “the study of pure design should be preliminary to the study of art in its various and specific applications.” They were partially reacting to the general misconceptions of design that it is mere decoration the aesthetics of which is handed down from a past time and commonly accepted. They explained:

Design, as it is commonly understood, is to serve the purpose of decoration or ornament by the various arts and crafts. The teaching of design means teaching “Historic Ornament,” the practice of design means following historic precedents and adapting them to modern requirements. It means doing what the public knows, understands, appreciates, wants. Design is the glass of fashion, the handmaid of commerce. In three words, it is not a fine art, as it should be. The creative imagination has very little to do with it.

(ibid., 38)

It was necessary to introduce pure design in order to draw attention to a new outlook. Pure design was a conceptual instrument for the understanding and application of the underlying formal structure in designs. This would reform the conventional perception of design as ornament and open up possibilities. According to Ross, pure design referred to abstract form detached from prescribed meaning and to relations between these forms. Ross’s intention was to use pure design and form relations as tools to comprehend how the visual and other material qualities play into the design process of an individual. He proceeded to show it in his pattern designs, and his analyses of paintings and photographs where he abstracted forms and looked at form relations.

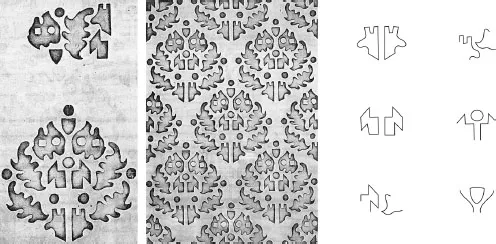

Ross published some of his wallpaper pattern designs along with his students’ exercises in Illustrations of Balance and Rhythm: For the Use of Students and Teachers (Ross et al., 1900). There is no text to explain the illustrations and the book is only a compilation of prints, but the arrangement of prints reveals a process of design to an extent. The prints are of mono-colored wallpaper patterns that are floral-looking in character. The patterns are composed of bizarre nonfigurative shapes. The darker outlines and the blotchy shading of the interiors of these enclosed shapes suggest that they were printed on the paper. In the particular arrangement of these prints, a set of these amorphous shapes precedes each design. These shapes are presented as building blocks that are then multiplied and put together in a design. An intermediary step arranges these little shapes together in a vertically symmetric unit that repeats to form the final wallpaper pattern. Each little shape performs, in turn, as a basic element of a wallpaper pattern. This reveals the process followed in the wallpaper pattern designs. The two images on the left in Figure 1.1 show the arrangement of such prints in Ross’s Illustrations of Balance and Rhythm in Plates 2 and 3. A set of amorphous shapes precedes each design. These units are assembled and together perform as the basic element of a wallpaper pattern. These are presented on the same plate in the book. The wallpaper pattern is then presented on the subsequent plate.

Figure 1.1 Left: The arrangement of prints of wallpaper designs and their compositional parts; right: spatial relations from wallpaper designs.

Sources: Left: Ross et al. (1900), Plates 2 and 3. Right: line drawings by the author.

The particular three-part presentation of each wallpaper pattern print in the publication is indicative of a process showing how the wallpaper pattern designs are created under Ross’s instruction. As already described above, this process starts with the set of amorphous abstract shapes. These shapes are atypical in the Modernist vocabulary of abstract forms and, instead, look almost organic. Some look like leaves, perhaps. They are then assembled creatively and together perform as the motif of a wallpaper pattern. The designed motif is repeated with vertical symmetries and off-axis rhythms in the overall wallpaper pattern as expected in such designs. The smaller units in the beginning, however, yield to more experimental arrangements. In the example in Figure 1.1, six shapes and multiple duplicates are organized symmetrically to fit inside the imaginary boundary of a larger onion-like shape. Some of the spatial relations here include edge and corner alignments as well as shapes or parts of shapes tucked into niches in other shapes or niches formed by groups of other shapes. These are shown in detail in the drawings on the right of Figure 1.1. The first three illustrate edge and corner alignments. The second three illustrate shapes or parts of shapes tucked into the niches in other shapes or formed by groups of other shapes. These spatial relations are not arbitrary. The designer establishes various spatial relations according to different perceptions of parts of the shapes.

Most of the units are amorphous with many features identifiable in many ways. How they come together relies more on their visual qualities in that particular context. For example, the circle sits in different niches each time, one of which is shown in Figure 1.1. Rather than being grouped with an equilateral triangle and a square as in the iconic twentieth-century basic design visual motto of basic elements, the circle in this case is explored in the context of a group of irregular shapes. Other than the formal expectations based on precedents in textile and wallpaper prints of the time, these decorative patterns do not have representational and functional qualities and are purely formal exercises. At the same time, they avoid idealized forms and form relations while simply constituting a medium to explore abstract forms. Even most of the duplicates slightly vary in size, by an extended edge, an extra curve or a trimmed end. The exercise allows for changes in shapes as well as their relations to one another.

It is not clear whether the little amorphous shapes in the examples here were appropriated from previous wallpaper designs, for example, by William Morris, or whether the students or Ross created them at that moment. The designs appeared to be Victorian damask where smaller and meaningless shapes come together to form motifs that resemble quatrefoil, bi-convex ellipses, or kite shapes. Illustrations in A Theory of Pure Design display similar shapes which Ross constructs in the course of the text using commonplace principles of harmony, rhythm, and balance. A Theory of Pure Design can be taken in parts as the instruction set for constructing shapes that can be used in these types of wallpaper designs. In that book, Ross (1907) shows how to construct various shapes, and eventually designs, out of parts. Figure 1.2 shows a variety of these shapes from A Theory of Pure Design, constructed out of points arranged in a gradient along a curve, various arcs lined up according to their tangents and normals, and shapes composed of other curves. He mostly relies on visual criteria.

Figure 1.2 Some elements of Pure Design.

Source: Ross (1907), pp. 25, 40, 41, 46, 65.

As for the origin of the wallpaper design units seven years prior to A Theory of Pure Design, there is no indication that the shapes were constructed carefully and intentionally. The shapes in the patterns are not symbols, and neither are they marks from brush strokes. Floral figures in Owen Jones’s ornaments catalogued in 1856 may have been common precursors (Stankiewicz, 1988, 84). Still, Ross’s use of these seems to parallel the intent to have unconventional figures that are difficult to deal with at the abstract level. These shapes are abstract motifs that transform natural forms such as petals, leaves, and stems but serve the same purpose. The level of abstraction resulting in the unfamiliarity of forms sets a distance between the students and the forms, so that they dismiss their biases and worry about establishing new and surprising relations between the forms. Without any concerns as to what the units are, these exercises focus on how one puts them together.

Moreover, there is little precision in how the shapes are drawn or printed. Form...