![]()

Chapter 1

Fermented Meat Products—An Overview

Friedrich-Karl Lücke

For Correspondence: Fulda University of Applied Sciences, P.O. Box 2254, 36012 Fulda, Germany. Tel: +49 661 9640 376, Fax +49 661 9640 399, Email:

[email protected]1 INTRODUCTION

Fermented meats are meat products that owe, at least partially, their characteristic properties to the activity of microorganisms. They may be subdivided into fermented sausages (made from comminuted meat) and meat products prepared by salting/curing entire muscles or cuts, followed by an ageing period in which enzymes (mostly meat proteases) bring about tenderness and flavor. In this chapter, such products are referred to as “ripened meats” (see also Toldrá 2015). Bacon and dried meats such as jerky and biltong are not considered here since there is little, if any, effect of microbial or tissue enzymes on their characteristics.

There are hundreds of different fermented meats. For example, the DOOR list of the European Union (http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/door/list.html) contains (as of July 2015), in the category Meat products, cooked, salted, smoked, etc., 117 entries as “Protected Geographic Indication” (PGI) and 34 entries as “Protected Designation of Origin” (PDO). Of these, the majority are fermented and/or ripened raw meat products, predominantly from the Mediterranean countries.

This chapter provides an overview on the types of fermented meats and on factors affecting their quality. It is not the intention of this chapter to describe all types of raw fermented and/or ripened meat products. Rather, they are classified by using a limited set of variables, and some examples for each category are given. For a more detailed account of the various types of fermented meats, their specific characteristics and their history, the reader is referred to the books edited by Toldrá (2015) and by Campbell-Platt and Cook (1995).

Salting and fermentation developed as a method to preserve meat in times before refrigeration became available. Hence, most traditional raw meat products are stable at ambient temperatures (after a salting/drying process). Some traditional sausages with short ripening time and high moisture content are normally cooked before consumption. Semidry fermented sausages mainly appeared on the market once starter cultures were introduced and the need for saving costs and reducing the fermentation time increased.

Ripened meat products prepared by salting/curing entire muscles or cuts are often referred to as “raw hams” because pork hams are nowadays most widely used as raw material. However, depending on regional traditions, other muscles and cuts (e.g. shoulder, M. longissimus dorsi) from various animals are used, too.

Quality parameters both for fermented sausages and ripened meats include:

• colour (affected by the type and amount of lean meat, curing agents, ageing time, pH, nitrate reductase activity);

• texture (affected by the type and amount of lean meat, method of comminution, acidification, drying and ageing time, weight loss);

• flavour (affected by the type and amount of lean meat, spices, acidification, ageing time);

• nutritional value (salt and fat content, fatty acid spectrum);

• safety (affected by levels of pathogens and contaminants in raw material and processing/ripening environment; lactic acid bacteria and fermentable carbohydrates in recipe; fermentation temperature and time; drying);

• shelf life (affected by composition of fatty tissue; spoilage flora in processing environment; lactic acid bacteria and fermentable carbohydrates in recipe; salting and/or fermentation time and temperature, relative humidity and time; drying).

Moreover, consumers have an increasing interest in the quality of production processes, namely, ecology (low input of energy, low output of waste and greenhouse gases etc.), animal welfare, and corporate social responsibility.

2 FERMENTED SAUSAGES

The following variables affect the characteristics of fermented sausages:

• Animal species and breeds for the lean meat component: these include pigs, cattle, small ruminants, poultry, horse, reindeer and game.

• Animal species for the fat component: pork back fat is preferred, especially for aged, high-quality products. The feeding regime is also important. If religious tradition prohibits the use of pork, fatty tissues from ruminants is used, such as sheep tail fat for Turkish sucuk (Kilic 2009).

• Cuts/muscles used. These vary in the percentage and composition of adherent fat and connective tissue, and pH value.

• Method for comminution of the meat: mincer or cutter.

• Degree of comminution of the meat: coarse, medium, or fine.

• Non-meat bulk ingredients from dairy (e.g. casein, milk powder) or plant origin. For example, potato flour and pre-cooked cereals may be used as extenders and binders, and some vegetables, especially paprika, for colour and taste.

• Spices (pepper, garlic, mustard seeds etc.).

• Additives; these include

– salt: sodium chloride

– curing agents (nitrite and/or nitrate) and adjuncts (ascorbate, isoascorbate)

– fermentable sugars of different types and ingoing amounts: glucose, sucrose, lactose, starch hydrolysates etc. A sugar derivative, glucono-δ-lactone (GdL), is hydrolyzed in the sausages shortly after stuffing, to give gluconic acid which is subsequently fermented into lactic and acetic acid. GdL is sometimes used as a chemical acidulant

– starter microorganisms (lactic acid bacteria, catalase-positive cocci, moulds or “house flora”). Various traditional fermentations still rely on the “house flora” but in order to standardize products and processes, use of commercial starter cultures is widespread, especially in industrial production

– other (e.g. polyphosphates, citrate, antioxidants).

• Type of casing (natural, semi-synthetic, synthetic), with different vapour permeability.

• Diameter of casing (may range from 1 to 15 cm).

• Fermentation conditions (time, temperature, relative humidity, air velocity).

• Surface treatment during or after fermentation: smoke, surface flora or none.

• Ageing (time, temperature, relative humidity, air velocity).

• Treatment of final product: slicing, packaging (material, gas atmosphere).

• Handling by the consumer: some products are cooked before consumption.

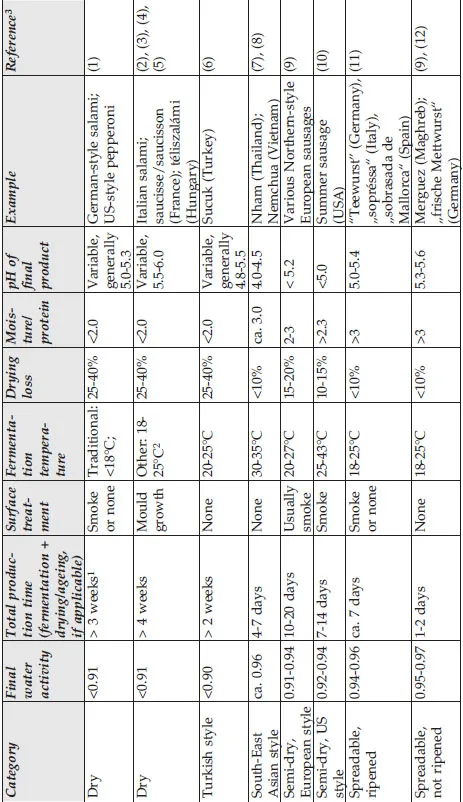

Table 1 shows the main categories for fermented sausages. Legally, classification is based on parameters such as moisture-protein ratio (e.g. in the USA), weight loss (e.g. in Austria), and lean muscle tissue (BEFFE; e.g. in Germany). Hence, the categories “dry”, “semi-dry”, “spreadable (ripened)”, and “spreadable (unripened)” are used in Table 1. However, there is no general clear, uniform distinction between dry and semidry fermented sausages in many countries, especially with traditional “artisanal” products: Many products having the same name can be prepared either as “dry” or “semi-dry” sausages, or, occasionally, even as unfermented hot-smoked product, and details, if any, are given in the small print part of the label. In Germany, for example, the “Leitsätze” (Codes of Practice; Anonymous 2014a) categorize fermented sausages either as “sliceable” (“schnittfest”) or “spreadable” (“streichfähig”). Within these categories, products are classified by the minimum content of muscle protein (total protein nitrogen × 6.25, minus collagen protein; German acronym “BEFFE”). Common formulations (with about 14% initial protein content and 2.5% ingoing sodium chloride) with a weight loss of about 25% result in a moisture/protein ration of 2.0 or below and a water activity of 0.91 or below. Such sausages can be classified as “dry” and microbiologically stable without refrigeration (Lücke 2015).

With respect to safety and stability, raw fermented and/or ripened meats may be divided into two categories, depending on whether or not they support growth of Listeria monocytogenes. According to Regulation (EC) No. 2073/2005 (Anonymous 2014b), up to 100 cells of L. monocytogenes can be tolerated if a food has a pH ≤ 4.4, or a water activity (aw) value ≤ 0.92, or a combination of pH ≤ 5.0 and aw value ≤ 0.94. If protected from undesired mould growth (e.g. by smoking, modified atmosphere packaging), sausages meeting this requirement are usually stable at 15°C or even without refrigeration. This applies to most, if not all, dry and semi-dry fermented sausages and many dry-aged hams while for meats not meeting this requirement, it is up to the manufacturer to provide scientific evidence that L. monocytogenes does not grow in his product.

2.1 European Dry and Semi-dry Sausages

The terms “Northern European Technology” and “Mediterranean Technology” have been coined by Flores (1997) and Demeyer et al. (2000). Briefly, “Northern-style sausages” have lower pH values (usually below 5.0 after fermentation) and are smoked after fermentation. Smoking meats is more common in regions where climatic conditions make it difficult to “air-dry” the meat products, e.g. in maritime or mountain regions with much rainfall and where firewood is easily available (see e.g. Holck et al. 2015). The manufacturing process of Mediterranean-style sausages is slower and results in products with low final water activity (and long shelf life at hot ambient temperatures) while pH values are usually 5.0–5.3 after fermentation and rise again during subsequent drying and ageing, especially if moulds and yeasts grow on the surface.

Table 1 Classification of fermented sausages

2.1.1 Dry and Semi-dry Sausages, “Northern European Style”

Most dry sausages typical for Northern and Eastern Europe are smoked, and mould-ripened sausages are uncommon. Traditionally, the sausages were prepared in winter and ripened at temperatures at 15°C or below for extended periods, so that they could be stored with little or no refrigeration for up to one year. By smoking, the sausage surface was protected from mould growth (especially in rainy climate) and rancidity development (Holck et al. 2015). However, so-called “air dried” sausages are common in Central Germany where specially designed loam-coated ripening chambers (“Wurstekammer”) provided a “low-tech” method to control the humidity (Lücke and Vogeley 2012). Traditional sausages were mostly made from pork (or, especially in mountain areas such as in Norway, from sheep meat), by use of a mincer to comminute the meat. The reason for this is that pigs can be slaughtered on farms more easily than cattle, and mincers, unlike cutters, can also comminute warm meat. For traditional product, nitrate and only low amounts of sugar (0.3 percent) are used, and starter cultures are rarely added. Nowadays, however, most of the fermented dry and semi-dry sausages in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe are prepared from chilled and frozen raw materials (pork and beef, the proportion between which depending on availability and desired colour) in the cutter, with 0.5% or more sugar, a combination of lactic acid bacteria and catalase-positive cocci as starters, and nitrite and ascorbate as curing agents. Fermentation is usually at 20–27°C, followed by a drying process at 10–15°C. The overall production time is generally about two to three weeks for thin dry sausages (or even less for thin snack sausages) and semi-dry sausages, and four weeks or longer for dry sausages of larger diameter (>60 mm). Certain sausages (e.g. “Landjäger”, “Kantwurst”) common in Southern Germany and Austria are pressed into moulds before fermentation. Categorization of German (Anonymous 2014a) and Austrian (Anonymous 2015) types of dry sausages is based on lean meat content, degree of comminution, and diameter, as determined by the casing used. In these countries, the term “salami” is used as a synonym for various dry sausage types of intermediate particle size, refers to various dry sausage types irrespective of surface treatment.

A review on dry sausages common in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe is given by Holck et al. (2015). As many designations indicate, there was a strong influence of German traditions. Differences are mainly caused by availability of different raw materials (such as lamb and mutton in Norway), by use of non-meat ingredients (such as potatoes and cereals in some Swedish sausages), paprika in the Danube region (“kolbász”, “petrovská klobása”, “kulen”; Kozačinski et al. 2006, Ikonić et al. 2010, Vuković et al. 2014), and spices. A special case is genuine Hungarian salami (“téliszalámi”, meaning “winter salami”) which...