- 578 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sex, Career and Family

About this book

In this book, first published in 1971, the authors show from first-hand studies of family and working life (and with evidence from many countries, including the socialist societies of Eastern Europe) the nature of the discrimination facing women in the professions – and how various family and employment patterns might contribute to solving it. Their point is not that some new stereotype should be substituted for traditional views of the role of husbands and wives: different patterns fit different situations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sex, Career and Family by Michael P. Fogarty,Rhona Rapoport,Robert N. Rapoport in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Introduction

Foreword

Are Women a Special Problem?

The terms of reference underlying this report are concerned with women, and in particular women and top jobs: how to get more of the former into the latter. As the study developed it extended not only to women in top jobs but to women’s opportunities in professional and managerial work at graduate level generally. It also focused increasingly – and this is the point the research team wish to emphasize in this Foreword – on the general pattern of relationships between men and women. Limitations of time and material have prevented the team from following out this approach as fully as they would have wished or as the title of the report implies. At a number of points this report will still give the impression of dealing with a ‘women’s question’. But the need to lay equal stress on rethinking the roles of men and women, not those of women alone, is a key part of the message which the team would like to convey. The case for careers for highly qualified women at a level commensurate with their abilities, and on an equal footing with men, can be argued on several grounds: personal interest and family need, civil rights, or, more cold-bloodedly, the need of the economy to use its biggest reserve of untapped ability. Whatever the ground of the argument chosen, if there is to be movement in this direction, it is necessary not only to develop woman’s own occupational competence and to break the barriers of discrimination, but also to work out new attitudes and relationships between men and women in the family as well as in working life.

The research team’s assumptions and conclusions on how to go about this are set out in the chapters that follow, especially in Chapters I, V and XIII. It will be noticed that the team has paid particular attention to ‘dual-career’ families as defined in Chapter IX. It is not the team’s intention to set up these families as a unique or universal model to which all should conform. The team’s own view is pluralistic. Many different patterns of family and working life are likely always to be needed to fit different talents and inclinations, and many options should be open. But ‘dual-career’ families are particularly interesting for the way in which they are pioneering – often, as will be shown, very successfully – a style of living which combines full participation for the wife as well as the husband in high-level employment together with the maintenance of the traditional values of family life. They do so in the face not only of the inherent problems and strains of the pattern of living which they have chosen, but also of misunderstandings, resistance and lack of material facilities which could be done away with if the value of their way of living were more widely appreciated.

But the point to stress here is not the value of any particular solution to the problem of rethinking sex roles in the light of the case for women’s careers. It is that as the study has proceeded its accent has come to be more and more on sex roles rather than on women. If the problems arising from women’s careers are to be successfully solved, men as well as women will need to join in working out a further series of changes – over and above the many which have already taken place – in men’s as well as women’s patterns of living; and men as well as women, as will be argued, have a strong interest in doing so.

Men and women, moreover, will not cease to be men and women in the process. One of the most significant findings of the family studies reported here is that dual-career and similar patterns do not imply masculine women or feminine men, any more than they need imply any disadvantage to children. Past views on this have been biased by the fact not only that those women who fought their way through the barriers of discrimination to reach top positions had often to be exceptionally tough – especially in the generation which made the first breakthrough – but also that so many of the women who reached these positions hitherto have been single. Women and men who remain single after usual marriage age tend, as will be shown, to diverge from the attitudes of their own sex towards those of the other. The present studies have paid special attention to married men and women, and in their case no necessary or even probable correlation appears between a wife having a career and the feminization of men or the masculinization of women.

Chapter I

The Special Problem of Women’s Promotion to Top Jobs

Why do Women Hold so Few of the Highest Posts?

In its initial concern with women’s employment at high levels this enquiry has had a double focus. It began by studying the discrepancy between women’s obvious contribution to the lower and middle ranks of many highly qualified professions and the much smaller number of women in higher posts. Women outnumber men by three to one among assistant teachers in the basic grade, but are outnumbered by men among the heads even of primary schools; by as much as six to one among the heads of comprehensive schools. Among hospital doctors in England and Wales women provide 25 per cent of house officers but only 7 per cent of consultants. In the Administrative Civil Service women provide 17 per cent of Assistant Principals but only 3 per cent of Under-Secretaries. At the moment there is no woman Permanent Secretary at all. Why do discrepancies like these exist, and what might be done about them? From this point of view the focus of the enquiry has been on top jobs in a relatively narrow sense. The research team’s preliminary broadsheet on Women and Top Jobs1 illustrated the dividing line between ‘top’ and lower jobs in this sense by examples such as:

Posts above and below the ‘top’ job line

| Industry | Head of a major division or function, company employing 2,000-5,000 | Senior manager in a similar company, responsible to the head of the major division or function |

| Civil Service | Under-Secretary (Assistant Secretary marginal) | Principal |

| Hospital Board | Consultant | Medical Assistant, Senior Registrar |

Is Women’s Progress Towards an Equal Share in Higher Professional and Managerial Work Generally Levelling Off?

But as the enquiry has proceeded it has developed a second and stronger focus on the constraints which seem still to be holding down women’s share in higher professional and managerial work generally, not only in posts at the very top. Women’s entry into a number of higher professions in Britain has followed a sequence from breakthrough to acceptance onto a plateau suggesting stagnation. In architecture, for example, the doors of the profession were opened by the 1920s, and by the 1950s a number of those who first came through them had established themselves as accepted senior practitioners. The number who reached the very top and were accepted as leaders of the profession was small, but, in proportion to the number of women practising, may if anything have been higher than among men. But the total number of women architects remained small, only around 4 per cent of all the architects practising, and showed no sign of rapid increase. Women architects had become an accepted but apparently permanent minority. In the Administrative Civil Service, the universities, and the higher ranks of the B.B.C. the story has been similar. Women doctors moved through the same stages a generation earlier, reaching by the 1920s and 1930s the standing which women architects reached by the 1950s. In politics the pattern has been similar though the timing has been different. The first woman M.P., Constance Markievicz, was elected in 1918, though as a Sinn Feiner and from 1919 a Minister in Dail Eireann she did not take her Westminster seat. The first woman actually to take a Westminster seat was elected at the end of 1919. By the 1930s women were well established in the House and there had been a woman Cabinet Minister. By the 1960s, if not by the 1950s, a noticeable proportion of women Members were of the standing which would let them reach for the top places in politics. But the total number of women M.P.s has remained small.

There are, of course, other fields in which women have still to achieve even the earlier stages of breakthrough and acceptance, in particular in the higher levels of business bureaucracy. Women owner-managers of small and medium firms are an accepted though once again a minority part of the business scene, but women at the top of the management ladder in big business hierarchies remain very rare indeed. The Oxford University Appointments Board noted in its report for 1968 that over 90 per cent of the public service jobs notified to it that year were open to women as well as men. In private industry and commerce, however, two-fifths1 of the jobs notified were closed to women; and whereas in the private sector women with specialist qualifications had relatively good opportunities – only 28 per cent of the technical jobs notified were closed to them – women were barred from 57 per cent of first jobs requiring a non-technical Arts qualification of the kind which women more commonly have. Half of all openings for articles with solicitors and accountants in private practice were also closed to women. Nationalized industries took an intermediate place with 72 per cent of jobs open and 28 per cent closed.

But the central question is: when women have come so far in so many higher professions, and not merely have doors been opened but many women have found that they can actually walk through them and on upwards to the top, why has further growth in the numbers who do so apparently been blocked? Between the Census years 1921 and 1931, in the decade immediately following the first opening of the doors to women in many professions, the number of women in higher professional work in Britain rose nearly twice as fast as the number of men, by 3 per cent a year against ·8 per cent. This was the classic decade of breakthrough. From 1931 to 1951 the two rates of growth were much closer together, though women still had a slight edge over men with an annual growth rate of 3·6 per cent against 3 per cent. But from 1951 to 1961 the number of men went on growing at 4·5 per cent a year while the number of women actually fell by nearly 1 per cent a year. The fall was accounted for mainly by a drop in the number of women professionally employed in religion. But the number practising medicine also fell, the number of women in science and the writing professions rose much more slowly than the number of men, and at a time when engineers were multiplying faster than any other major profession, and surveyors and accountants were also increasing fast, the report from which these figures are taken continued to record women in these fields as ‘too few to show separately’. In higher administrative, professional and managerial work as a whole the number of women rose in these years in England and Wales from 40,000 to 50,000, at 1 ·7 per cent a year, but the number of men rose from 450,000 to 660,000 at 3·8 per cent.2

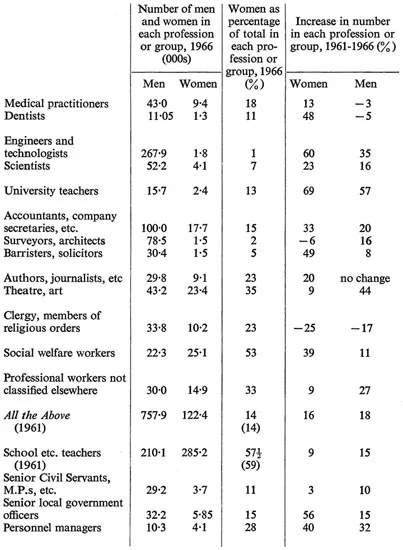

This actual fall in women’s share in higher professions did not continue through the first half of the 1960s, but neither did women resume their advance. The percentage of ‘managers, large establishments’ in England and Wales who were women was almost exactly the same at the Census for 1966 as at that of 1961 (Table I.1). So was the percentage of women in a range of higher professions (Table I.2); excluding the biggest, school teaching, in which the percentage of women fell. In some individual professions women made dramatic proportional gains, but for the group of higher professions as a whole this was offset by the fact that some of the biggest increases in the absolute number of professional people employed were in professions where women are only weakly represented. So, for instance, the number of women engineers and technologists classified as such1 grew faster than the number of men, but in absolute figures the increase was 700 for women and 70,000 for men. Spread over the grand total of all men or women in the higher professions, the former figure influences the average rate of increase very little, whereas the latter influences it a great deal.

Table I.1 Men and Women ‘Managers, Large Establishments’, England and Wales Censuses of 1961 and 1966

| Number (000s) | 1961 | 1966 |

| Men | 517.3 | 548.2 |

| Women | 76.4 | 81.9 |

| Total | 593.7 | 630.1 |

| Women as per cent of Total | 12.9 | 13.0 |

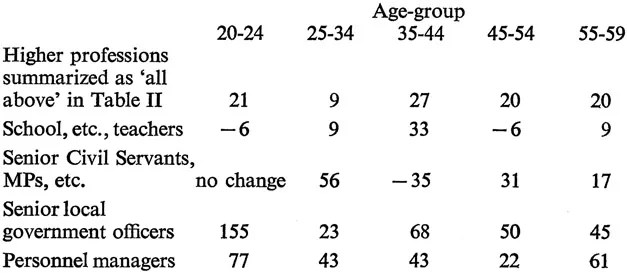

Nor do the 1961-66 figures suggest that the pattern of recruitment has been such as to lead automatically to a big advance in women’s share in the higher professions over the next few years. This would be the case if, for example, the increase in the number of women working in the professions had been concentrated at entry ages. In that case it could be expected that the overall percentage of women in each profession would rise as the big new contingents came in behind them. Different professions have of course different recruitment problems and patterns, but on the average of the whole group of higher professions it seems (Table I.3) that the increase in the number of women was evenly spread over entry and older age groups, though with a relatively small increase in the main child-bearing age group, 25-34. Inland Revenue figures for the middle 1960s shows that whereas women represented nearly one-third of all employees, they were outnumbered by men

Table I.2 Men and Women Active in Certain Professions, England and Wales, Censuses of 1961 and 1966

by twenty to one in the range of P.A.Y.E. incomes from £2,000 to £2,999 and by fifty to one above £5,000.1 Neither the Census nor any other figures show any automatic reason to expect this sort of relationship to change greatly in the next few years.

It is common to find that the graph representing the development of some social custom or practice or the advancement of a group is S-shaped. There is a slow start, a rapid acceleration as the new development takes hold, then a tendency for the curve to flatten as a state of equilibrium is reached. The curve of women’s movement

Table I.3 Increase per cent in the number of women in certain age groups in certain professions, Great Britain, Census of 1961 and 1966.

into a number of higher professions has clearly followed this pattern, and a state of at least temporary equilibrium has been reached. The question is: is this equilibrium a permanent resting place, or is it (what is also commonly found) a pause before moving into a new S-curve of further advance? If and when the gates of sectors such as large-scale business management, of certain technical professions, where women’s opportunities are still formally or informally more restricted, are opened wider, can one expect that there too the number of women who actually pass through the gates will stabilize itself at a low level?

The Blocked Road to the Top – A by-Product of the General Conditions of Women’s Employment?

In one way the answer might seem to follow simply from a consideration of women’s position in employment generally. Stu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Origional Title

- Origional Copyright

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

- PART TWO: AN INTERNATIONAL REVIEW OF EXPERIENCE

- PART THREE: STUDIES OF FAMILY AND WORK CAREERS

- PART FOUR: OCCUPATIONAL PROSPECTS

- PART FIVE: CONCLUSIONS

- XIII. THE ENQUIRY’s FINDINGS AND THE FUTURE

- STATISTICAL AND TECHNICAL APPENDICES

- SUBJECT INDEX

- NAME INDEX