eBook - ePub

Conversion and Islam in the Early Modern Mediterranean

The Lure of the Other

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The topic of religious conversion into and out of Islam as a historical phenomenon is mired in a sea of debate and misunderstanding. It has often been viewed as the permanent crossing of not just a religious divide, but in the context of the early modern Mediterranean also political, cultural and geographic boundaries. Reading between the lines of a wide variety of sources, however, suggests that religious conversion between Christianity, Judaism and Islam often had a more pragmatic and prosaic aspect that constituted a form of cultural translation and a means of establishing communal belonging through the shared, and often contested articulation of religious identities. The chapters in this volume do not view religion simply as a specific set of orthodox beliefs and strict practices to be adopted wholesale by the religious individual or convert. Rather, they analyze conversion as the acquisition of a set of historically contingent social practices, which facilitated the process of social, political or religious acculturation. Exploring the role conversion played in the fabrication of cosmopolitan Mediterranean identities, the volume examines the idea of the convert as a mediator and translator between cultures. Drawing upon a diverse range of research areas and linguistic skills, the volume utilises primary sources in Ottoman, Persian, Arabic, Latin, German, Hungarian and English within a variety of genres including religious tracts, diplomatic correspondence, personal memoirs, apologetics, historical narratives, official documents and commands, legal texts and court records, and religious polemics. As a result, the collection provides readers with theoretically informed, new research on the subject of conversion to or from Islam in the early modern Mediterranean world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conversion and Islam in the Early Modern Mediterranean by Claire Norton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Renaissance History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Trans-imperial subjects

Geo-political spatialities, political advancement and conversion

1 Trans-imperial nobility

The case of Carlo Cigala (1556–1631)1

Introduction

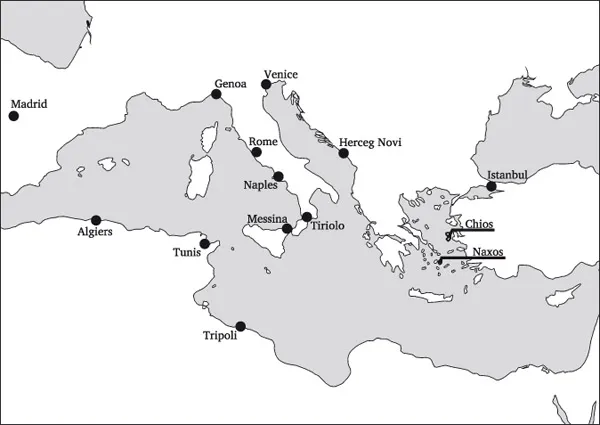

On 15 Rebiülahir in the year 1007 after the Hijra (12 November 1598), Sultan Mehmed III issued a certificate of appointment (berat) to a certain ‘Carlo Cigala who lives in Messina’. According to the sultan’s orders, the man was ‘to bring, without delay and hesitation, … [his] mother and [to] go to the … Duchy of Naxos and enjoy and govern it in … [his] lifetime’.2 Messina, of course, was not part of the sultan’s ‘well-protected domains’, nor was Cigala one of his subjects. This imperial command, therefore, presents somewhat of a puzzle. Why would Mehmed III appoint a foreigner – and a subject of his greatest rival in the Mediterranean, the king of Spain, at that – to what was nominally a vassal state, yet effectively a sancak of the Ottoman Empire? Taking Carlo Cigala’s appointment to the Duchy of Naxos as a starting point, this article examines the links between members of the Cigala family and the Ottoman Empire. I argue that, at least as far as Carlo was concerned, Christendom’s “archenemy” had a crucial role to play in his quest for social advancement. In fact, Carlo aspired to be, and indeed considered himself to be, part of a trans-imperial nobility.3

To begin, however, it would be prudent to briefly comment on the main source for Carlo Cigala’s appointment to the Duchy of Naxos since the quotation from the berat is taken, not from an Ottoman original, but from an Italian translation preserved in the archives in Venice. At first glance, this may make the information rather spurious. Yet Joshua White, who has had the chance to compare a number of copies and translations of Ottoman documents from this period preserved in Venice to their originals in Istanbul, has concluded that the Venetian material is generally faithful and therefore reliable.4 In this particular instance, the genuineness of the sultan’s order is supported by the close correspondence of the Italian text to Ottoman diplomatics which, in fact, makes it possible to classify the command as a berat in the first place. Phrases such as ‘give faith to my imperial seal’, with which the body of the document ends, are commonplace elements to authenticate the document and affirm its validity.5 While this does not preclude the possibility that the berat kept in Venice is a forgery that is very unlikely, all the more so since the translation is contained among the dispatches of the Venetian baili in Istanbul who stood to gain nothing from spreading false rumour in this case.

Figure 1.1 Map of the Mediterranean

Source: Drawn by the author using geographical data provided by Natural Earth.

The Cigala family

The Cigalas were one of Genoa’s old noble families. Carlo’s father Visconte had been born in the city in 1504 but later relocated to Messina. The Sicilian port was an ideal basis of operations for Christian corsairs like Visconte who targeted Muslim shipping. Apart from undertaking private raids in the Mediterranean, Carlo’s father on several occasions sailed with the famous admiral Andrea Doria and participated in Charles V’s naval campaigns in North Africa and against the Ottomans. The Cigala family also maintained close connections to the Vatican. While Visconte’s brother achieved the rank of a cardinal, two of his nephews by another brother joined the Jesuits.6 He himself had two daughters and three sons, of whom Carlo was the youngest.7

By the time Mehmed III issued the ferman for Carlo’s appointment to the Duchy of Naxos, the latter enjoyed considerable social standing in his own right. His wife Beatrice de Guidici was the daughter of a Messinese baron and, according to the Venetian bailo Matteo Zane, by the early 1590s, Carlo was the recipient of ‘a pension of five hundred scudi annually’ from the king of Spain.8 In 1597, moreover, the Sicilian had been granted the title of count by the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II.9

In Carlo’s efforts to further enhance his prestige as much as that of his family, his elder brother played a crucial role. For, when the sultan saw fit to promote the younger Cigala in the Aegean, Carlo’s brother, who had been named Scipione by their parents, was none other than the Ottoman kapudan paşa, the admiral of the Ottoman fleet, Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha. Most probably born in 1544, Scipione Cigala was seventeen years old when he and his father were captured at sea by Maghrebi corsairs in 1561, one year after the disastrous defeat of the Spanish fleet at Djerba. The two men were brought first to Tunis and then to Istanbul where Visconte Cigala was imprisoned in the fortress of Yedikule while Scipione converted to Islam and entered the school of Topkapı Palace.10 Admission to the school destined him for a prestigious career in Ottoman state service and made his subsequent professional biography virtually indistinguishable from those of illustrious recruits of the devşirme, the infamous ‘boy levy’, such as Sokollu Mehmed Pasha.11 Less than two years after his graduation from the inner palace in 1573, he was appointed agha of the janissaries. He received his first provincial governorship, in Basra, after the outbreak of war with Safavid Iran in 1578.12 In the following years, he distinguished himself on the Eastern battlefield, notably in the conquest of Tabriz during the campaign of 1585.13 As early as 1579, he briefly assumed command of the Ottoman forces in the East when the current commander-in-chief (serdar), Grand Vizier Lala Mustafa Pasha, was summoned to Istanbul.14 In recognition of his services, Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha was promoted to the rank of vizier in 1583. As the war with Iran drew to a close after thirteen years of fighting, he finally secured the appointment which he had desired for years: the office of the kapudan paşa.15

When Mehmed III succeeded to the throne after Murad III’s death in 1595, the Italian-born admiral was dismissed as part of the usual reshuffling of positions in the Ottoman administration which accompanied a new sultan’s accession.16 In the following year, still out of office, he accompanied the sultan on campaign in Hungary where the so-called Long War with the Austrian Habsburgs had broken out in the summer of 1593. This campaign saw not only the conquest of the fortress of Eger (German: Erlau, Turkish: Eğri) by Ottoman troops, but also, in its aftermath, the effective routing of the Ottoman camp on the nearby plain of Mezőkeresztes. By several accounts, Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha played a crucial role in turning the tide of battle at the last minute, as a reward for which he was appointed grand vizier. However, owing to palace intrigues as well as the harsh treatment of alleged deserters, he was relieved of his duties after little more than a month.17 Subsequently, he was posted first to Damascus and finally reappointed to the kapudanlık in 1598. This time, he remained in office even when Ahmed I succeeded to the throne in December 1603.18 When the Italian-born pasha was removed from his post the following year, it was because his talents as a military commander were once again required in the Eastern provinces where a new war with Iran had broken out.19 He died during that campaign in 1606.20

During his lifetime as well as in the memory of later generations, Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha enjoyed considerable fame not just in the Ottoman Empire, but also in Christian Europe. In the middle of the seventeenth century, for example, a man claiming to be a son of the late admiral became the object of public attention. Although this self-styled Jean Michel de Cigala/Mehmed Bey in all probability was an impostor unconnected to the actual Cigala family, he had managed to convince the king of France of the truth of his claim. The episode, as Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha’s biographer Gino Benzoni has remarked, provides ‘eloquent testimony of the enduring fascination of the Christian world with the figure of Cigala, who remained an enigma in the West’.21 As late as the nineteenth century, the kapudan paşa appeared as the main character in an homage to William Scott by the German novelist Philipp Joseph von Rehfues, while the Italian singer/songwriter Fabrizio de Andrè dedicated a song to “Sinàn Capudàn Pascià” in 1984.22

Carlo Cigala’s quest for the Duchy of Naxos

Against the background of his success in climbing the Ottoman hierarchy, Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha sought to re-establish contact with his family in Sicily. Sometime after his first appointment as kapudan paşa, the convert invited his younger brother Carlo to visit him in Istanbul, an invitation which the latter accepted in 1593. News of this journey instantly gave rise to the rumour that the younger Cigala had been dispatched by the king of Spain in order to breathe new life into negotiations for a truce with the Porte.23 If Carlo had indeed been on such a mission, it came to naught. In any case, during a meeting in the Ottoman capital, he reassured Bailo Matteo Zane ‘that he [was] here on his own private business alone’.24

That ‘private business’, however, was more than merely a reunion between two brothers. According to the Venetian diplomat’s relazione delivered to the Doge and Senate after his return from Istanbul in 1594, ‘the said Signore Carlo … was indulging in the belief that he could easily be given charge of Moldavia or Wallachia by paying the usual pension to the Porte. And when this turned out unsuccessful he hatched the idea of having the islands of the Archipelago in imitation of the [sultan’s] Jewish favourite Giovanni Miches [Joseph Nasi]’.25 In this undertaking, Carlo certainly hoped to benefit from his brother’s position in the Ottoman military-administrative elite, not least because Naxos and the other islands of the Cyclades, which were part of the historical duchy, were subject to the kapudan paşa’s jurisdiction.26 Although Carlo had arrived in Istanbul with high hopes, they remained unfulfilled for the time being. After several months, he returned to Messina empty handed because, as Zane put it, ‘his brother the Capudan … [would] not support him’.27

On the surface, Carlo’s visit to Istanbul appears rather unusual. Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha’s invitation certainly contradicts the prevailing stereotype that conversion necessitated the severance of all previous ties to kith and kin expressed by Ottoman and Christian-European contemporaries alike.28 By and large, however, such contacts between converts and their families, even outside the Ottoman Empire, were a rather ordinary phenomenon. Maria Pia Pedani has drawn attention to the fact that, during the same period, a number of Venetians visited family members who had entered the Ottoman elite. Some of them stayed, others even converted themselves.29 Thanks to Eric Dursteler’s recent work, the best-known example of this pattern is certainly provided by the Venetian Michiel family which included the eunuch Gazanfer Agha one of the most powerful men of his day, and his sister Beatrice, who after her conversion became known as Fatima Hatun.30 That Gazanfer Agha had one of Fatima’s sons abducted from a Venetian boarding school and brought to Istanbul, where he, too, embraced Islam, makes it one of the most spectacular cases of such continuing contacts between converts to Islam in the Ottoman Empire and their families ‘back home’.31

Carlo Cigala’s hope to receive his brother’s patronage likewise finds parallels in the stories of Venetian families. Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha’s immediate predecessor in the kapudanlık, Uluç Hasan Pasha, for instance, petitioned the Venetian Sen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1 Trans-imperial subjects: geo-political spatialities, political advancement and conversion

- Part 2 Fashioning identities: conversion and the threat to self

- Part 3 Translating the self: devotion, hybridity and religious conversion