![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

In this chapter we introduce model-based development and UML-RSDS, and discuss the context of software development which motivates the use of such methods and tools.

1.1 Model-based development using UML-RSDS

Model-based development (MBD) is an approach which aims to improve the practice of software development by (i) enabling systems to be defined in terms closer to their requirements, abstracted from and independent of particular implementation platforms, and (ii) by automating development steps, including the writing of executable code.

A large number of MBD approaches, tools and case studies now exist, but industrial uptake of MBD has been restricted by the complexity and imprecision of modelling languages such as UML, and by the apparent resource overheads without benefit of many existing MBD methods and tools [3, 5, 6, 7, 8].

UML-RSDS1 has been designed as a lightweight and agile MBD approach which can be applied across a wide range of application areas. We have taken account of criticisms of existing MBD approaches and tools, and given emphasis on the aspects needed to support practical use such as:

■ Lightweight method and tools: usable as an aid for rapidly developing parts of a software system, to the degree which developers find useful. It does not require a radical change in practice or the adoption of a new complete development process, or the use of MBD for all aspects of a system.

■ Independent of other MBD methods or environments, such as Eclipse/EMF.

■ Non-specialist: UML-RSDS uses only a core subset of UML class diagram and use case notations, which are the most widely-known parts of UML.

■ Agile: incremental changes to systems can be made rapidly via their specifications, and the changes propagated to code.

■ Precise: specifications in UML-RSDS have a precise semantics, which enables reliable code production in multiple languages.

The benefits of our MBD approach are:

■ Reduction in coding cost and time.

■ The ability to model an application domain, to define a DSL (domain specific language) for a domain, and to define custom code generators for the domain.

■ Reducing the gap between specification and code, so that the consequences of requirements and specification choices can be identified at an early development stage.

■ The ability to optimize systems at the platform-independent modelling level, to avoiding divergence between code and models caused by manual optimization of generated code.

■ The ability to formally analyse DSLs and systems at the specification stage.

These capabilities potentially reduce direct software development costs, and costs caused by errors during development and errors persisting in delivered products. Both time-to-market and product quality are potentially improved.

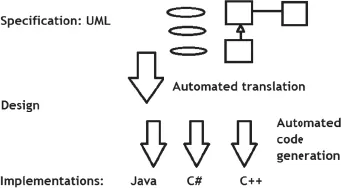

Figure 1.1 shows the software production process which is followed using UML-RSDS: specifications are defined using UML class diagrams and use cases, these can be analysed for their internal quality and correctness, and then platform-independent designs are synthesised (these use a pseudocode notation for a subset of UML Activity diagram notation). From these designs executable code in a particular object-oriented programming language (currently, Java, C# or C++) can then be automatically synthesised.

Figure 1.1: UML-RSDS software production process

Unlike many other MBD approaches, which involve the management of multiple models of a system, UML-RSDS specifies systems using a single integrated Use Case and Class Diagram model. This simplifies the specification and design processes and aligns the approach to Agile development practices which are also based on maintaining a single system model (usually the executable code).

Some typical uses of UML-RSDS could be:

■ Modelling the business logic of an application and automatically generating the code for this, in Java, C# or C++.

■ Modelling and code generation of a component within a larger system, the remainder of which could be developed using traditional methods.

■ Defining a model transformation, such as a migration, refinement, model analysis, model comparison, integration or refactoring, including the definition of custom code generators.

UML-RSDS is also useful for teaching UML, OCL, and MBD and agile development principles and techniques, and has been used on undergraduate and Masters courses for several years. In this book we include guidance on the use of the tools to support such courses. An important property of MBD tools is that the code they produce should be correct, reliable and efficient: the code should accurately implement the specification, and should contain no unintended functionality or behaviour. To meet this requirement, the UML-RSDS code generators have been developed to use a proven code-generation strategy which both ensures correctness and efficiency.

In the following chapters, we illustrate development in UML-RSDS using a range of examples (Chapter 2), describe in detail the UML notations used (Chapters 3, 4 and 5) and the process of design synthesis adopted (Chapter 6). Chapter 7 describes how model transformations can be expressed in UML-RSDS. An illustrative example of UML-RSDS development is given in Chapter 8.

Chapter 9 describes design patterns and refactorings that are supported by UML-RSDS. Chapter 10 explains how UML-RSDS systems can be composed. Chapters 11, 12 and 13 describe how migration, refinement and refactoring transformations can be defined in UML-RSDS. Chapters 14 and 15 describe how bidirectional, incremental and exploratory transformations can be defined in UML-RSDS. Chapters 16, 17 and 18 describe in detail the development process in UML-RSDS, following an agile MBD approach. The development of specialised forms of system is covered in Chapters 19 (reactive systems) and 20 (enterprise information systems).

Chapter 21 describes how the tools can be used to support UML, MBD and agile development courses, and gives examples of case studies and problems that can be used in teaching.

The Appendix gives technical details of the UML-RSDS notations and tool architecture.

1.2 The ‘software crisis’

The worldwide demand for software applications has been growing at an increasing pace as computer and information technology is used pervasively in more and more areas: in mobile devices, apps, embedded systems in vehicles, cloud computing, health informatics, finance, enterprise information systems, web services and web applications, and so forth. Both the pace of change, driven by new technologies, and the complexity of systems are increasing. However, the production of software remains a primarily manual process, depending upon the programming skills of individual developers and the effectiveness of development teams. This labour-intensive process is becoming too slow and inefficient to provide the software required by the wide range of organisations which utilize information systems as a central part of their business and operations. The quality standards for software are also becoming higher as more and more business-critical and safety-critical functionalities are taken on by software applications.

These issues have become increasingly evident because of high-profile and highly expensive software project failures, such as the multi-billion pound costs of the integrated NHS IT project in the UK [4].

New practices such as agile development and model-based development have been introduced into the software industry in an attempt to improve productivity and quality. Agile development tries to optimize the manual production of software by using short cycles of development, and by improving the organization of development teams and their interaction with customers. This approach remains dependent on developer skills, and subject to the limits which hand-crafting of software systems places on the rate of software production. Considerable time and resources are also consumed by the extensive testing and verification used in agile development.

Model-based development, and especially model-driven development (MDD) attempts to automate as much of the software development process as possible, and to raise the level of abstraction of development so that manually-intensive activities are focussed upon the construction and analysis of models, free from implementation details, instead of upon executable code. Model transformations are an essential part of MBD and MDD, providing automated refactoring of models and automated production of code from models, and many other operations on models. Transformations introduce the possibility of producing, semi-automatically, many different platform-specific versions of a system from a single platform-independent high-level specification of a system.

MBD certainly has considerable potential for industrializing software development. However, problems remain with most of the current MBD approaches:

■ The development process may be heavyweight and inflexible, involving multiple models – such as the several varieties of behaviour models in UML – which need to be correlated and maintained together.

■ Support tools may be highly complex and not be interoperable with each other, requiring transformation ‘bridges’ from tool to tool, which increases the workload and possibilities for introducing errors into development.

■ The model-based viewpoint conflicts with the code-centered focus of traditional development and of trad...