- 524 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Neurosciences and the Practice of Aviation Medicine

About this book

This book brings the neurosciences to operational and clinical aviation medicine. It is concerned with the physiology and pathology of circadian rhythmicity, orientation, hypotension and hypoxia, and with disorders of the central nervous system relevant to the practice of aviation medicine. The chapters on circadian rhythmicity and orientation deal with the impaired alertness and sleep disturbance associated with desynchrony and with the effects of linear and angular accelerations on spatial awareness. Hypotension and hypoxia cover cerebral function during increased gravitational stress, clinical aspects of exposure to acute hypoxia, the mild hypoxia of the cabin of transport aircraft, adaptation and acclimatization to altitude and decompression at extreme altitudes and in space. Disorders of particular significance to the practice of aviation medicine such as excessive daytime sleepiness, epilepsy, syncope, hypoglycaemia, headache and traumatic brain injury are covered, while neuro-ophthalmology, the vestibular system and hearing also receive detailed attention. The potentially adverse effects of the aviation environment and of disorders of the nervous system are brought together, and the text covers the neurological examination as it relates to aircrew and explores current management and therapeutics. The Neurosciences and the Practice of Aviation Medicine is an essential work for those involved in the practice of aviation medicine where familiarity with the effects of the aviation environment on the nervous system and understanding the pathophysiology of relevant clinical disorders are of prime concern. The authors from leading centres of excellence are physiologists concerned with the aviation environment and physicians involved in the day-to-day practice of medicine. They bring to this authoritative text wide experience and expertise in both the experimental and clinical neurosciences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Neurosciences and the Practice of Aviation Medicine by Anthony N. Nicholson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

WAKEFULNESS, AWARENESS AND CONSCIOUSNESS

Understanding impaired responsiveness in aircrew demands familiarity with the aviation domain and with relevant aspects of the neurosciences, both physiological and clinical. The manifestations of the adverse effects of the aviation environment and of some clinical disorders have much in common. Wakefulness may be impaired when aircrew have difficulty in coping with irregularity of their rest and activity, and excessive daytime sleepiness occurs with some disorders of sleep. Impaired awareness can lead to illusions or the loss of orientation. Awareness is prejudiced by excessive arousal, by inadequate or incorrect sensory information linked mainly to the visual and vestibular systems, and by incorrect or inadequate processing of the information as in coning of attention and errors of expectancy (Benson, 1999). Consciousness may be impaired during exposure to positive accelerations as well as by hypoxia, by trauma and by various transient and episodic disorders of the nervous system.

States of Responsiveness

The states of wakefulness, awareness and consciousness are crucial to the aviator. Wakefulness is an enabling state (Rees et al., 2002) that underpins vigilance (a state of keeping watch for possible difficulties – Oxford English Dictionary). It involves the physiological event of arousal. It is a state that can be impaired by disturbed sleep. Awareness and consciousness are less well defined and the terms are used varyingly in different disciplines. It is, therefore, useful to explore what can be meant by awareness and consciousness, and how these states relate to the aviation domain.

Awareness involves perception and in aviation it is especially concerned with the appreciation of the spatial environment. It involves the sense of location in relation to the immediate and the remote surroundings. Awareness facilitates the sensory input essential to orientation and, when impaired, leads to disorientation. However, awareness (with perception) is not necessarily concerned with the interpretation of information. The interpretation of what is perceived in the wakeful state is a higher nervous function – consciousness. Awareness does not create consciousness, though it modulates the process that leads to the conscious state. The nature of consciousness itself is uncertain, and attempts to understand consciousness involve the disciplines of philosophy and neuroscience.

In summary, as far as aviation is concerned, vigilance (watching for possible difficulties) is dependent on the wakeful state and may be impaired by disturbed sleep and circadian dysfunction, while orientation is prejudiced by loss of awareness. Clearly, both vigilance (dependent on the wakeful state) and orientation (dependent on awareness) have much relevance to air safety. The operational significance of consciousness, though little understood in itself, is obvious. Hypotension during increased gravitational stress (positive acceleration) and hypoxia during exposure to altitude are potent threats to the integrity of a phenomenon that involves sensory, central (introspective) and purposeful motor functions.

The identification of the anatomical substrates for these states of responsiveness and understanding the physiological basis of wakefulness, awareness and consciousness are of much interest in the neurosciences. It would appear that central structures of the nervous system are pivotal. The activities of the peripheral sensory systems do not create wakefulness, awareness or consciousness – they modulate pre-existing states. Initially, as far as sleep and wakefulness were concerned, the importance of the sensory input was much emphasized. However, in the middle of the twentieth century, studies concerned with the physiological basis of this continuum shifted the emphasis from a primarily sensory process to one involving central structures in the brainstem and, in due course, studies implicated the midbrain and projections toward the cortex.

Similarly, during the latter part of the same century and to date, studies on spatial awareness are shifting the emphasis of the processing of information from the sensory organs to structures within the medial temporal lobe with possible projections to the parietal cortex. As far as consciousness is concerned, recent studies have raised the possibility that the thalamocortical system is involved, and the confirmation of the neural substrate for consciousness would set aside forever the myth of dualism.1 There may well be a long way to go before responsiveness is adequately understood, but it is worthwhile to review briefly the present state of knowledge and the possibilities opened up by recent research.

Wakefulness

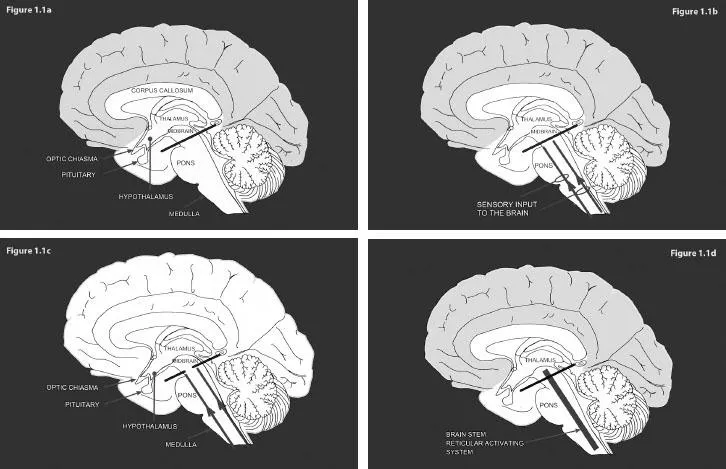

Due to the efforts of experimental and clinical neurophysiologists throughout most of the twentieth century and onwards to this day, there is now a reasonable understanding of the physiological basis of the sleep–wakefulness continuum. Present-day understanding of the wakeful state originated with the studies of Bremer (1935, 1938). Continuous sleep was observed in animals with transection of the brain at the boundary between the brainstem and the cerebrum (Figure 1.1a), and it was considered that this state was due to the loss of the sensory input to the cortex (Figure 1.1b). That interpretation was in keeping with generally held views on the nature of sleep at the turn of the nineteenth century, and even from ancient times.2 The observations provided experimental evidence for the importance of the brainstem in the control of sleep and wakefulness. However, as the transection was at the boundary between brainstem and cerebrum, the brain was not entirely devoid of sensory input and so there were difficulties with the emphasis that was placed on sensory input.

Reticular Activating System

The solution emerged when Moruzzi and Magoun (1949) identified the reticular activating system within the brainstem. Awakening was not impaired if sections at the level of the brainstem similar to those used by Bremer (1935, 1938) were limited to the sensory pathways (Figure 1.1c). It was the section of the central core of the brainstem that led to sleep (Figure 1.1d), and it was the ascending influences arising from the reticular formation that were responsible for wakefulness. These, and later studies (Batini et al., 1958), indicated that neurons located in the anterior part of the upper third of the pons were predominantly responsible for wakefulness while neurons of the lower third of the brainstem dampened the process of wakefulness and could actively induce sleep.

The reticular activating system within the brainstem is an essential network, though not the unique structure, as far as the generation of sleep and wakefulness is concerned. It has now been established that structures concerned with the control of sleep and wakefulness extend well into the cerebrum. The anterior part of the pons, the midbrain, posterior hypothalamus and basal forebrain structures are concerned with wakefulness while the lower brainstem (nucleus tractus solitarius), anterior hypothalamus and the basal forebrain are involved with sleep promotion. Studies have also shown that spindles and slow-wave activity during sleep are dependent on the activity of the thalamocortical system (Steriade, 2001) and that such activity is generated between the thalamus and the cortex and modulated by the systems of the brainstem, hypothalamus and basal forebrain (Steriade and Deschenes, 1984; McCormick and Bal, 1997; Amzica and Steriade, 1998).

Figure 1.1 Schematic depiction of the studies by Bremer (1935, 1938) and Moruzzi and Magoun (1949) (see colour section)

Source: Nicholson, A.N. 1998. The Neurosciences and Aviation Medicine: A Century of Endeavour. International Academy of Aviation and Space Medicine, Auckland: Uniprint (L.J. Thompson (ed.) with permission from the Academy).

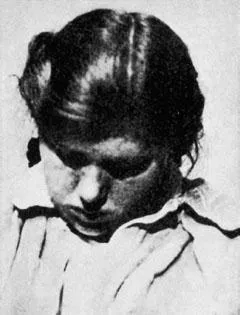

Circadian System

The full manifestation of the sleep–wakefulness continuum involves not only the arousal system projecting from the brainstem, but also the circadian system. A circadian influence in humans was anticipated by the observation of Fulton and Bailey (1929) working in the surgical clinic of Harvey Cushing (1869–1939). They observed that the rhythm of sleep and wakefulness was disturbed in a young woman with a tumour just above the pituitary. Minnie had experienced transient attacks of drowsiness for several years. She was even unable to stay awake to have her photograph taken (Figure 1.2) and she would often drop off to sleep in the company of friends even when the conversation was said to be animated. The attacks of drowsiness became progressively more severe and more prolonged, and somnolence became almost continuous. She died at the age of 24 years.

It was patients like Minnie that encouraged discussion on the rhythmic nature of sleep and wakefulness during the early part of the twentieth century. The paper by Fulton and Bailey (1929) contained almost a prophecy: ‘It was, perhaps, erroneous to speak of a sleep centre in the brain, but tumors above the pituitary gland may disturb the rhythm of sleep and wakefulness.’ This appears to be the first suggestion in the clinical literature that the alternating pattern of sleep and wakefulness was somehow related to a specific part of the brain, and, in turn, that whatever may be involved in the control of sleep and wakefulness there was a rhythmic input.

Source: Fulton, J.F. and Bailey, P. 1929. Tumors in the region of the third ventricle: their diagnosis and relation to pathological sleep, 69, 1–25. (With permission from Wolters Kluwer Health).

It is now well established that a pacemaker exists near to the pituitary gland, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, and that it receives input from the eyes through the retinohypothalamic tract. The emerging complexities of the physiology and pharmacology of the circadian system are dealt with in Chapter 2 (Circadian System and Diurnal Activity). As far as aviation is concerned, the potential significance of the circadian system to the efficiency of aircrew was explored initially by Klein et al. (1970), and its implications to the work of aircrew, together with those of the sleep–wakefulness continuum, are dealt with in Chapter 3 (Aircrew and Alertness).

Electroencephalography

Over the same years that progress was being made in understanding the anatomy and physiology of sleep and wakefulness, there was an increasing interest in the human electroencephalogram and its relation to the behavioural manifestations of the sleep–wakefulness continuum. The electrical activity of the brains of animals had been recorded in the nineteenth century (Caton, 1875), but the first recordings in humans were made by Berger (1929). Adrian and Matthews (1934a, 1934b) then explored the variations and abnormalities of the waves in the electroencephalogram and showed that the alpha rhythm disappeared when the individual was attentive or in deep sleep.

Later, Loomis et al. (1937) described the changes in the electroencephalogram with the states of sleep, and that led to the manual published by the National Institutes of Neurological Diseases and Blindness (Rechtschaffen and Kales, 1968), since revised by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (Iber et al., 2007). These manuals provide definitions for the identification of wakefulness, drowsiness, various stages of sleep and arousals, and have been supplemented by recordings of peripheral activities relevant to the assessment of sleep disorders. A brief description of these recordings, intended to introduce the aeromedical practitioner to polysomnography, is given in Chapter 10 (Investigation of Sleep and Wakefulness in Aircrew).

The potential of electroencephalography for clinical medicine was soon appreciated. Electroencephalography is now an essential feature of the assessment of neurological disorders that prejudice responsiveness, and so are particularly relevant to the practice of aviation medicine. These are considered in Chapter 11 (Excessive Daytime Sleepiness: Clinical Considerations) and Chapter 12 (The Diagnosis of Epilepsy). Sleep electroencephalography has also proved to be a useful tool for the investigation of disturbed sleep in aircrew as it has enabled the accurate measurement of wakefulness in relation to rest periods. Such studies are described in Chapter 3 (Aircrew and Alertness).

Awareness

Awareness facilitates perception and is dependent on the wakeful state. It is a state wherein information becomes accessible. However, awareness does not imply that what is perceived is adequately interpreted. Interpretation demands higher nervous activity when the individual is ‘aware of being aware’, and that state is consciousness. Awareness makes perception possible and what is perceived may modify pre-existing consciousness, but awareness does not create consciousness. It must also...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Authors and Affiliations

- 1 Wakefulness, Awareness and Consciousness

- 2 Circadian System and Diurnal Activity

- 3 Aircrew and Alertness

- 4 Spatial Orientation and Disorientation

- 5 Cerebral Circulation and Gravitational Stress

- 6 Oxygen Delivery and Acute Hypoxia: Physiological and Clinical Considerations

- 7 Hypobaric Hypoxia: Adaptation and Acclimatization

- 8 Profound Hypoxia: Extreme Altitude and Space

- 9 The Neurological Examination: Aeromedical Considerations

- 10 Investigation of Sleep and Wakefulness in Aircrew

- 11 Excessive Daytime Sleepiness: Clinical Considerations

- 12 The Diagnosis of Epilepsy

- 13 Syncope: Physiology, Pathophysiology and Aeromedical Implications

- 14 Hypoglycaemia and Hypoglycaemia Awareness

- 15 Headache

- 16 Traumatic Brain Injury and Aeromedical Licensing

- 17 Neuro-Ophthalmology

- 18 Vestibular and Related Oculomotor Disorders

- 19 Disorders of Hearing

- Appendix I A Bibliography of Case Reports of Neurological Disorders in Aircrew

- Appendix II International Standards for Hearing Measurements, Aircraft Noise and Vibration Control

- Appendix III World Health Organization Descriptors of Hearing Impairment

- Index