- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

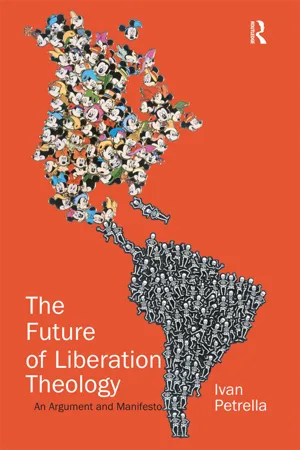

The Future of Liberation Theology envisions a radical new direction for Latin American liberation theology. One of a new generation of Latin American theologians, Ivan Petrella shows that despite the current dominance of 'end of history' ideology, liberation theologians need not abandon their belief that the theological rereading of Christianity must be linked to the development of 'historical projects' - models of political and economic organization that would replace an unjust status quo. In the absence of historical projects, liberation theology currently finds itself unable to move beyond merely talking about liberation toward actually enacting it in society. Providing a bold new interpretation of the current state and potential future of liberation theology, Ivan Petrella brings together original research on the movement, with developments in political theory, critical legal theory and political economy to reconstruct liberation theology's understanding of theology, democracy and capitalism. The result is the recovery of historical projects, thus allowing liberation theologians to once again place the reality of liberation, and not just the promise, at the forefront of their task.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Future of Liberation Theology by Ivan Petrella in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

ReligionChapter 1

Liberation Theology Today: the Missing Historical Project

Latin American liberation theology was born at the crossroads of a changing Catholic church and the revolutionary political–economic ferment of the late 1960s and early 1970s.1 In the first case, the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) opened the door for a fundamental rethinking of the relation between Christian faith and the world by asserting the value of secular historical progress as part of God’s work. Papal social encyclicals such as Mater et Magistra, Pacem in Terris and Populorum Progressio focused not just on worker’s socioeconomic rights but also on the rights of poor nations in relation to rich nations. In addition, Vatican II gave greater freedom to national episcopates in applying church teaching to their particular contexts. In the second case, the Cuban revolution, the failure of the decade of development and Kennedy’s ‘Alliance for Progress’, as well as the exhaustion of import substitution models of development led to the rejection of reformist measures to ameliorate the massive poverty that plagued Latin America.2 Political and economic views became increasingly radical as groups of priests, workers and students organized in militant revolutionary groups that espoused socialism. At the same time, starting with Brazil in 1964, a succession of military coups led to the imposition of national security states. These two trends, religious and political, came together at the Second General Conference of Latin American Bishops (CELAM) at Medellin, Colombia in 1968. Documents from this meeting began by analyzing Latin America’s social situation.3 They argued that the continent suffers from an internal and external colonialism caused by a foreign exploitation that creates structures of institutionalized violence. Mere development, the documents asserted, could not overcome this condition of dependency. The concept of liberation emerged as an alternative.4

Liberation theology’s foundational texts, those of its inception and expansion, were written from within this worldview.5 They share the following presuppositions: (a) a sharp dichotomy between revolution and reformist political action, the first seen as necessary while the second is deemed as ineffectual or as an ideological smokescreen that supports the status quo; (b) the poor were seen as the primary, and at times exclusive, agents of social change; (c) a sharp dichotomy between socialism and capitalism, socialism as the social system that could remedy the injustice of the latter; and (d) priority was given to politics in the narrow sense of struggle over state power, with little attention to issues of gender, ecology, race and popular culture.

But liberation theology’s historical context – that is, the sociopolitical and religious context within which liberation theologians work – has changed dramatically since the late 1960s and 1970s.6 At the ecclesial level, the main changes lie in the rise of Pentecostal groups and the Vatican’s clampdown on liberation theology by silencing theologians and replacing progressive bishops with conservative ones.7 At the same time, however, Vatican documents have incorporated central liberationist concepts such as the preferential option for the poor and liberation. On the political and economic fronts, the first change lies in the collapse of socialism. In my mind, all the other changes need to be understood in relation to the demise of the socialist alternative. For liberation theology, the fall of the Berlin Wall represents the loss of a practical alternative to capitalism.8 In fact, the prospect of an alternative seems to have disappeared from view. One has to go back to the beginning of industrial capitalism in the 19th century to find a similar period.9 A second change lies in the perceived decline of the nation state’s ability to control economic activity within its own boundaries. The third change lies in the upsurge of culture as a politically contested site and the subsequent downgrading of the traditional political sphere, the struggle for state power.10

Liberation theology finds itself on the defensive and is perceived as struggling to respond adequately to this new context. In this chapter I present and assess the three ways liberation theologians have responded to this situation: reasserting core ideas, revising or reformulating central categories and the critique of idolatry. Perhaps because the bulk of the material remains untranslated, these moves remain unrecognized in the North Atlantic academy; surprisingly however, they have yet to be properly theorized by the liberation theologians themselves. The chapter is divided into two parts. First, I present and critique the three positions; I will suggest that they all suffer from a common defect – the inability to devise concrete alternatives to the current social order. They are thus ultimately incapable of fulfilling liberation theology’s promise, the promise of a theology that, not content merely to discourse about liberation, actually seeks to further liberation. Second, I turn to liberation theology’s foundational texts to recover the idea of a historical project and suggest that the lack of this concept in recent work is both a symptom and a cause of its current impasse.

Current Responses in Liberation Theology

Liberation theologians have developed three moves in response to the fall of socialism and shift in their historical context. I call these moves ‘reasserting core ideas’, ‘reformulating or revising basic categories’, and ‘critiquing idolatry’, whether of the market or of modernity at large. While the same theologian may make more than one move in the same work, the differences in emphasis remain pertinent enough to separate analytically each position.

Reasserting Core Ideas

This position disentangles liberation theology’s core ideas – concepts such as the preferential option for the poor, the reign of God and liberation – from Marxism as a social scientific mediation and socialism as a historical project.11 It builds on a number of essays that sought to separate liberation theology from the death of socialism symbolized by the fall of the Berlin Wall.12 The argument is simple and can be stated in three steps: (a) liberation theology was never intrinsically tied to any particular social–scientific mediation or historical project; (b) the discrediting of a particular mediation and/or historical project thus cannot affect liberation theology’s core intuitions or ideas; (c) the current worldwide situation of growing inequality makes liberation theology’s central intuitions as necessary as ever.

This position admits a change in the context within which liberation theology is done. According to Gustavo Gutiérrez:

In the past years we have witnessed a series of economic, political, cultural and religious events, on both the international and the Latin American plane, which make us think that important aspects of the period in which liberation theology was born and developed have come to an end.... Before the new situations many of the affirmations and discussions of that time do not respond to today’s challenges. Everything seems to indicate that a new period is beginning.13

Gutiérrez then separates the essential from the inessential in liberation theology:

Theologies necessarily carry the mark of the time and ecclesial context in which they are born. They live insofar as the conditions that gave them birth remain. Of course, great theologies overcome, to an extent, those chronological and cultural boundaries, those of lesser weight – no matter how significant they might have been for a time – remain more subject to time and circumstance. We are referring, certainly, to the particular modes of a theology (immediate stimuli, analytical instruments, philosophical notions, and others), not to the fundamental affirmations concerning revealed truths.14

For Gutiérrez, in the particular case of liberation theology, that essential revealed truth ‘revolves around the so-called preferential option for the poor. The option for the poor is radically evangelical, and thus constitutes an important criterion to separate the wheat from the chaff in the urgent events and currents of thought in our days’.15 Notice that Gutiérrez distinguishes the revealed truths of theology from the vehicles that carry those truths. There is thus a distinction to be drawn between liberation theology’s revealed content and the socioanalytical tools used to explicate that content. The discrediting of a particular mediation does not touch the preferential option for the poor as the core of liberation theology.

Jon Sobrino, like Gutiérrez, begins his reassertion of core ideas by stressing the need to rethink liberation theology in the light of current events.16 He then proceeds to make the notion of ‘liberation’ the central element: ‘What is specific to liberation theology goes beyond particular contents and consists of a concrete way of exercising intelligence guided by the liberation principle.’17 For Sobrino ‘liberation is not just a theme, even if the most important, but a starting point: it ignites an intellectual process and offers a permanent pathos and particular light. This ... is the fundamental aspect of liberation theology’.18 Sobrino too, therefore, separates essential from inessential elements in liberation theology. Liberation is not a ‘content’ but a guiding light and principle. Liberation, therefore, cannot be tied down to any particular political program or philosophical analysis but precedes and guides them. They come afterwards; their failure does not disprove the guiding principle.19

José Maria Vigil provides a final example of the reassertion of core ideas. He stresses that liberation theology never had its own model of society, but had and continues to have a Christian utopia that orients its work within history.20 For this reason, ‘the crisis of the model of society inspired by socialism will inevitably reflect back on liberation theology, but at the level of its practical references rather than its principles’.21 For Vigil, a ‘strategy of liberation has failed, not Liberation itself’.22 For him, ‘if we wanted to express the paradigm in a word we would choose this one: the Reign! That would be liberation theology’s paradigm, because it is, in reality, Jesus’ paradigm!’23 Vigil, given the separation between essential and inessential elements in liberation theology, draws the same conclusion as Gutiérrez and Sobrino: ‘We will be able to (and will have to) update as much as necessary at the level of theology’s mediations, but we have the feeling that the paradigm itself remains undefeated.’24

To recapitulate the first position outlined: one strategy pursued by theologians in the face of the shift in their political, economic and cultural context lies in the reassertion of liberation theology’s core ideas. The theologian separates a central element, whether it be the preferential option for the poor, liberation or the Reign of God, and asserts that despite all this element remains untouched. The impulse behind this position is correct. It is true that liberation theology, despite what many critics claim, rarely fully identified with any mediation or historical project. Thus the discrediting of such a mediation does not touch the heart of liberation theology with its focus on the poor, the construction of God’s reign and liberation. Liberation theologians are right to argue that in an increasingly divided world these elements remain as necessary as ever. The way these elements are defended, however, exacts too high a cost. What allows this position to work is the emptying of the idea defended. It is no longer clear what the preferential option for the poor, the Reign of God and liberation mean in practice without the incorporation of some sort of social scientific mediation, whether Marxist or not; without such mediation it remains impossible to provide alternatives to the current global order.

All three theologians tacitly acknowledge the need for new mediations but make no headway in their incorporation. Sobrino writes that ‘liberation theology makes of God’s Reign its central content and conceives itself as the adequate theory for its construction’.25 ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Liberation Theology Today: the Missing Historical Project

- 2 Liberation Theology as the Construction of Historical Projects

- 3 Liberation Theology, Democracy and Historical Projects

- 4 Liberation Theology, Capitalism and Historical Projects

- 5 Liberation Theology, Institutional Imagination and Historical Projects

- 6 Liberation Theology as the Construction of Historical Projects Revisited

- 7 Conclusion

- Appendix The Present and Future of Latin American Liberation Theology: a Manifesto in Eight Parts

- References

- Index