![]()

1 Aims/expectations of airline deregulation

1.1 US Experience with Tight Economic Regulation

It was the Contract Air Mail Act of 1925 that enabled scheduled air transport services to become a permanent feature of the US scene for the first time. The Act introduced a system of contracts for the carriage of mail by air so providing the necessary stable financial environment for the development of such services. An amendment of the Act in 1930 gave considerable power to the Postmaster General who was able to use this to restructure the industry into a small number of trunk carriers operating transcontinental routes. However, the method used by the holder of this office to allocate air mail contracts was the subject of considerable controversy and resulted in a national scandal and the revocation of all existing contracts.1 The Air Mail Act of 1934 was the outcome of this debacle and introduced a highly bureaucratic system of control involving no fewer than three separate regulatory bodies.2 As Levine (1975) comments, given this dispersion of responsibilities carriers were able to abuse the system by submitting very low bids in the certain knowledge of having them later made profitable by the Interstate Commerce Commission. A number of fatal crashes in the three years following this Act led to strong pressure for the establishment of an organisation that was to be devoted exclusively to matters of air transport.

The Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) was set up in 1938 as a direct consequence of this and was given power to regulate pricing and entry on interstate routes, determine mail rates, and control all aspects of safety.3 One of its first activities was to grant 'grandfather' rights4 to the 23 carriers then in existence, who later became referred to as trunk carriers.5 After the war these carriers faced competition from newly formed charter operators, who had been able to acquire aircraft and trained air crew at low cost. Charter services had been exempted from regulation by the CAA in 1938 and as a consequence operators were able to charge substantially lower fares than their scheduled counterparts. The trunk carriers reacted by introducing 'coach' fares, which as Davies (1972) shows had such a significant impact that by the end of the 1940s this class of traffic formed a large component of total demand. The Civil Aeronautics Board's reaction to this was to protect the scheduled carriers by attempting to restrict the operations of charter airlines, imposing limits on the number of flights they could undertake. A number of carriers managed to circumvent these restrictions by operating under a variety of different names, resulting in a higher provision of charter services than the regulatory authority had intended. Scheduled carriers could have responded to this competition by reducing prices, but the CAB was not enthusiastic about authorising low fares for such operations, a policy for which it was criticised by the US Senate in 1951.6 In responding to this criticism the Board adopted a strategy of encouraging the trunk airlines to apply for coach fares, whilst simultaneously prohibiting charter operators from running anything remotely resembling a regular service. The dichotomy between scheduled and non-scheduled operations in US airline markets was thus established.

In a similar manner, CAB sought to protect the original 23 airlines by expanding its regulatory net to include the activities of cargo charter carriers who by then had started to make inroads to their markets. Indeed, apart from the approval of some Local Service airlines who were themselves strictly prevented from competing with trunk carriers, the authority maintained a complete ban on new entrants until the mid 1970s. It did however seek to increase the amount of non-price competition between scheduled carriers by licensing two or three trunk airlines on most city-pair markets. By 1970 of the top 135 city-pair markets, based on a combination of the top 100 ranked in terms of passenger numbers and the top 100 in terms of passenger-miles, ninety had two competitors and 38 had three.7 CAB's stated objective in so doing was...' ..to assure the sound development of an air transportation system properly adapted to the needs of the foreign and domestic commerce of the United States, of the Postal Service, and of the national defence.'8

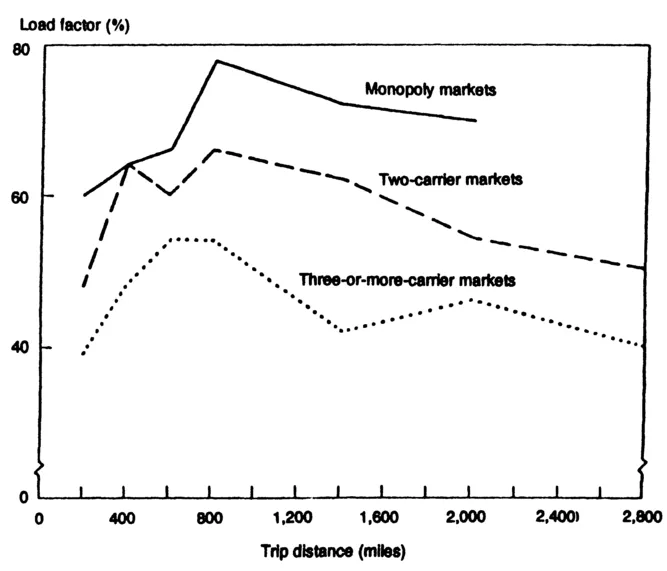

Although by today's standards it seems ironic, the Board came under fierce criticism for this pro-competition policy. Bluestone (1953), for example, argued that the main result of attempting to introduce competition in this way had been to increase operating costs. On city-pairs with two or more licensed carriers, given an inability to vary prices competition had manifested itself in the form of increases in service frequency, resulting in lower load factors and higher unit costs. Profitability suffered as a consequence, leading to demands from the trunk carriers for higher fares. Fruhan (1972), using data from the mid 1960s, showed that load factor declined as the number of rivals on a route increased.9 Figure 1.1 summarises his findings. Douglas (1971) using 1969 data for individual airlines in selected city-pairs confirmed this and showed a more pronounced downward trend in average load factors than those indicated by Fruhan. By using a range of time valuations for travellers ($5-$10 per hour) Douglas had attempted to calculate optimum load factors on routes of differing length. Eads (1975) analysed these results and concluded that.. '..during the late 1960s load factors were below optimal on all but relatively shorthaul monopoly routes.' This situation worsened considerably in the 1970s with carriers incurring substantial losses as a result of this and other forms of intense service rivalry.10

Figure 1.1 Load Factors by Trip Distance and Number of Rivals Source: Fruhan, W. E. (1912), The Fight for Competitive Advantage: A Study of the United States Domestic Trunk Air Carriers, Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration, p. 54.

One explanation for this was revealed by Taneja (1968) who modelled the relationship between a carrier's output and its market share in individual city-pair markets. The resulting S shaped relationship is now widely accepted and shows clearly that a unilateral decision by one carrier to reduce capacity on a route will result in a proportionally greater reduction in market share. Airlines faced with this situation according to Fruhan (1972) were placed in the familiar position of the 'prisoner's dilemma'11, producing an outcome that none of them desired. Collusive action between carriers on a route could have resulted in an increase in average load factor, but this would have been only likely to have occurred under very stable market conditions. Eads (1975) attributes blame for this inefficiency on the CAB who through their willingness ..'..to grant fare increases when industry profits were low, regardless of evidence that the problem resulted from scheduling rivalry, has put the Board in a position of actually encouraging such rivalry.'

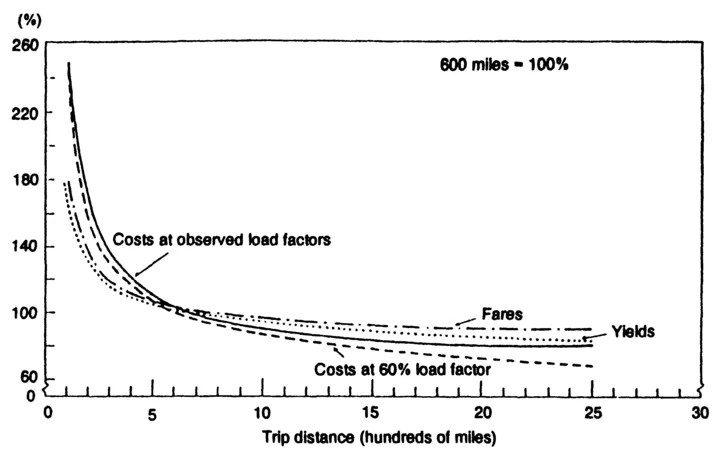

A policy of cross-subsidising short haul routes with long haul operations had also been pursued by the CAB. Eads (1975) shows this clearly in a graphical representation of unit costs and average yields by route length using 1965/6 data. This is reproduced below in figure 1.2. That fares were allowed to exceed costs by an increasing margin as route length increased above about 600 miles, enabled long haul services to operate at lower load factors, as is indicated in figure 1.1 Competition from ground transportation provides some explanation for this as Gronau's (1970) research into modal choice revealed. At distances up to approximately 600 miles, road and, in certain instances, rail transport provide a viable alternative to air travel.12 That this mileage coincides with the CAB's cross-subsidy boundary is entirely logical and confirms the regulator's primary preoccupation of ensuring adequate provision of services to small communities.

By the early 1970s the approach favoured by a majority of economists involved the dismantling of as many economic controls as possible, allowing market forces free rein. Kahn (1971) summarised the consensus viewpoint by pointing out ..'..that these cost-inflating service improvements have not been subjected to the test of having to compete with lower cost, lower service alternatives'. Attempting to eliminate the inefficiencies resulting from excessive service rivalry in any other way was fraught with difficulty. The Federal Aviation Act specifically prevented the CAB from constraining service frequency, whilst the other option of reducing the number of competitors on a route could realistically be achieved only through merger or the sale of a licence. To expect carriers of their own volition to agree to either of these courses of action required there to be a substantial commonality of interest. In the main, as Eads (1975) comments, this was unlikely to have been a realistic expectation.

Figure 1.2 Unit Costs and Average Yields by Route Length Source: Eads, G. C. (1975), 'Competition in the Domestic Trunk Airline Industry: Too Much Or Too Little?'; chapter 2 of Promoting Competition in Regulated Markets, edited by Almarin Phillips, The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, p. 36.

Considerable weight was added to the deregulation cause from the experience gained in California of intrastate airline operations. On such routes the CAB had no jurisdiction, the controlling authority being the state's Public Utilities Commission whose only concern was in regulating price increases. As a consequence, airlines serving this market had been able to engage in price competition. The net impact of this was that over routes of comparable distance fares were considerably lower than on interstate city-pair markets. Jordan (1970) estimated that in the absence of regulation interstate trunk fares in 1965 would have been 32% to 47% lower than they actually were.13 He had compared fares on Californian intrastate routes operated by Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) with CAB regulated trunk fares in the Northeast Corridor of the country. Problems of strict comparability arose however because of the congested nature of airline operations in the latter area. Jordan attributed the success of PSA, the then leading Californian intrastate carrier, to its low fare policy and greater efficiency, which he asserted were the outcome of less regulation.

It is worth exploring the PSA case as it provided protagonists with considerable evidence in support of their case for deregulation. That the airline's lower unit costs were derived from a number of sources is clear. A key factor had been their ability to employ non-unionised pilots on a mileage flown basis, whereas trunk carriers were severely constrained in this matter by section 401 of the Civil Aeronautics Act. Considerable economies could be achieved by concentrating on high density routes with common features. For example, PSA were able to use just one aircraft type configured for single class operation. In addition, by having the flexibility to vary fares, they were able to avoid matching the expensive service improvements of their trunk rivals. Given that all this had occurred as a result of having fewer economic constraints, it seemed reasonable to presume that this would be repeated in other markets if regulation was generally made less restrictive. That a large number of Californian intrastate airlines had failed was not regarded as being of any great consequence. Though trunk carriers had by comparison not been allowed to go under.14

1.2 Expectations of Deregulation Advocates

The overwhelming weight of evidence compiled by researchers during the 1960s convinced most observers that the CAB's primary preoccupation with protecting the airlines it had been given jurisdiction of in 1938, could no longer be regarded as being in the public interest. Forty years of tight regulation had resulted in an inefficient, stultified scheduled airline industry. A major concern of those regulating the industry had been to protect licence holders, with comparatively little regard being given to matters of efficiency or the interests of consumers. However, rather than pressing for a gradual change in the regulatory system, most interested parties favoured complete economic deregulation. The consequences of this decision forms the basis of the following chapter.

The fundamental and inevitable necessity for each carrier to provide its own protection against the competitive onslaught was given little, or no, serious consideration by those that advocated full scale economic deregulation. Entry barriers were perceived erroneously to be low, this judgement being based on observations of the small number of relatively non-regulated scheduled markets then existing. In the US it was widely anticipated that the overall effect of the passing of the Airline Deregulation...