![]()

Chapter One

Introduction

With antient Worthies, Chandos, shalt thou Live In Verse, if I a living Verse can give…1

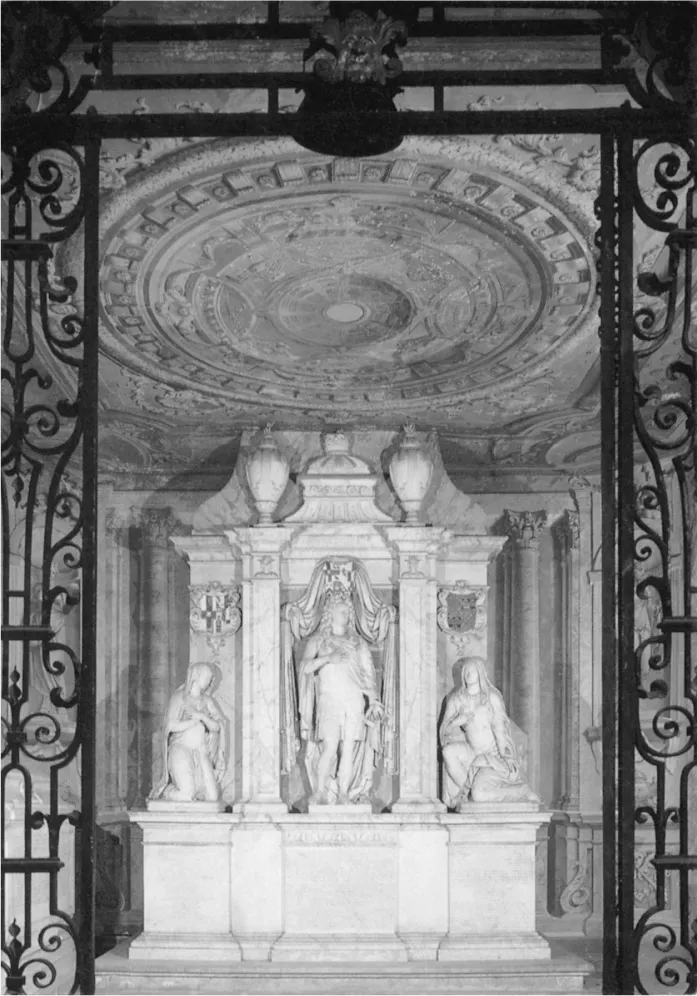

James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos (1674–1744) was forty-three years old in 1717, when he commissioned Grinling Gibbons (1648–1721) Master Sculptor and Carver in Wood to the Crown, to produce marble statues for his tomb monument.2 At that moment his fortune seemed secure, his new palace, Cannons, was nearing completion and in 1719 he was rewarded for his loyalty to the new Hanoverian monarchy with a ducal coronet. Less than twenty years later, in 1736, when the full-length statues, carved in grey and white marble, were moved into their current position in the mausoleum at St Lawrence, Whitchurch in Stanmore, the Duke’s financial position was precarious. After his death, eight years later, his house and collection were sold off to avoid bankruptcy.3 The tomb monument commissioned by the Duke as a memorial to himself and his family remains as one of the few objects associated with him to survive for posterity. Brydges’ story is the tale of an individual’s rise from the ranks of the lesser nobility to its highest levels. Through the patronage of Queen Anne and her Captain-General, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough (1650–1722), he amassed such a large personal fortune that his contemporaries at one time believed him to be the richest man in England. He used his wealth to build and furnish his palatial country seat, Cannons, near Edgware and acquire a magnificent collection of paintings and manuscripts. The poet and critic Charles Gildon (1665–1724) described him as ‘England’s Apollo’ and proclaimed that:

The Arts in him have now a patron found,

To them his Bounty does diffuse around.4

Brydges was an important figure in the social and cultural world of the early eighteenth century. As an architectural patron, he employed leading architects such as William Talman (1650–1719), James Gibbs (1682–1754), John James (c.1672–1746), Sir John Vanbrugh (1664–1726) and John Wood the Elder (1704–54). As a patron of art, he commissioned work from the great painters of the day: Sir Godfrey Kneller (c.1646– 1723), Michael Dahl (c.1659–1733), Antonio Bellucci (1654–1726) and Sir James Thornhill (c.1675–1734). His interest in music and literature led him to patronise George Frederick Handel (1685–1759), who lived at Cannons from 1717 to 1719, where he composed the ‘Chandos Anthems’ and the poet John Gay (1685–1732). In 1720, Gay wrote a poetic tribute which identified Chandos as one of the most important patrons of the period. In his Poems on Several Occasions, the poet linked Chandos with Richard Boyle, 3d Earl of Burlington (1694–1753), who was the most celebrated architectural innovator of the age, and praised them both as ‘enlightened patrons … and patriotic heroes… striving to domesticate a taste for Continental art’.5

Censure will blame, her breath was ever spent

To blast the laurels of the Eminent.

While Burlington’s proportion’d columns rise,

Does he not stand the gaze of envious eyes?

Doors, windows are condemn’d by passing fools

Who know not that they damn Palladio’s rules.

If Chandois with a lib’ral hand bestow

Censure imputes it all to pomp and show:

When if the motive right were understood,

His daily pleasure is in doing good.6

Gay’s tribute indicates that whilst Chandos was recognised as an important patron of the arts, he was criticised for his patronage and his motivation was mistrusted. The great Augustan poet Alexander Pope (1688–1744) attacked him in his poem Of Taste (first published in 1731). The poem describes the tasteless country residence of an aristocrat called Timon, whom contemporaries identified as the Duke of Chandos. The literary giant Samuel Johnson (1709–84) lent weight to this interpretation, commenting that Timon: ‘was universally supposed and by the Earl of Burlington, to whom the poem is addressed, was privately said, to mean the Duke of Chandos, a man perhaps too much delighted with pomp and show’.7 More recent criticisms of the Duke’s taste have dismissed it as ‘uninformed and unsure’ and vilified his house as an example of outdated Baroque architecture, which misappropriated features of the new Palladian style.8 Chandos has been accused of having ‘a very distinct trace of vulgarity’ and of showing no ‘real appreciation of artistic problems’.9

The fact that the Duke’s house and collection did not survive his death in 1744, makes it more difficult to evaluate his importance as a patron. His heir, Henry, 2nd Duke of Chandos (1708–71) was forced to auction every fixture and fitting in the house to pay off the family’s debts.10 The dearth of surviving artefacts has resulted in a misunderstanding of Chandos’s role as an enlightened and active patron and collector. This study seeks to reappraise the Duke’s patronage and his cultural importance.

This is not the first time that a writer has chosen to champion the Duke of Chandos’s cause.11 In 1949, he was the subject of a comprehensive and sympathetic biography written by Charles Collins Baker, former Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and his wife, Muriel.12 Using the large archive of the Duke’s correspondence in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, they addressed his role as a patron of the liberal arts and provided a wealth of biographical detail relating to him and his family. The couple offered an extensive account of the building of Cannons, concluding that the house was simply one of the many new Palladian buildings under construction during the first half of the eighteenth century. They did not seek to present a rounded portrait of the Duke in the context of other collectors of the age. It is hoped that this book will fill that gap and, with the benefit of new material published in the last twenty-five years, situate Chandos within the cultural context of early eighteenth-century attitudes towards the arts.13

The Duke of Chandos was one of the greatest patrons of the first half of the eighteenth century and his patronage should be examined in relation to recent developments in art historical thought and literature. As a particular type of eighteenth-century collector – an aristocrat who created, rather than inherited the fortune with which he built up his outstanding collection of art and books – studies of the Duke investigate many of the recent areas of research that have occupied art historians and other scholars.

Among the issues that have dominated the social and cultural context of eighteenth century studies over the last twenty-five years is a complex debate about conspicuous consumption, and an associated analysis of luxury, taste, connoisseurship and ‘politeness’. The question of conspicuous consumption was first explored in the work of social and economic historians McKendrick, Brewer and Plumb (1982), who argued that an unprecedented demand for luxury items in the first half of the eighteenth century, paved the way for the Industrial Revolution at the end of the century, leading to the birth of our modern, consumerist society.14 Successive historians have examined the impact of conspicuous consumption (or ‘luxury’) on society and revealed contemporary concerns about its corrupting effect on taste, that were satirised in popular prints of the day. The argument between Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713) and Bernard Mandeville (1670–1733) author of The Fable of the Bees, or Private Vices, Publick Benefits (1714), indicated how threatening ‘luxury’ was considered to be.15 Shaftesbury opposed the immorality of Mandeville’s argument that the unbridled pursuit of personal pleasure was in the public interest because it would contribute to a thriving economy. As a philosopher, he encouraged the wealthy to fulfil their national duty by developing a ‘national’ school of native artists and architects, arguing that the models for ‘right taste’ should be drawn from the classical, Roman past.

Shaftesbury’s writings contributed to a growing art literature on connoisseurship, in which Jonathan Richardson senior (1667–1745) played an important part as both theorist and practitioner of art.16 New ideas about good taste began to circulate in a society in which contemporaries were concerned with the ‘correct way’ to spend money. The gentlemanly pursuit of scholarship became associated with ‘connoisseurship’, and with the belief that there was such a thing as a ‘right taste’.17 Recent art historical research has shown the importance of this period for the development of connoisseurship and collecting, a period in which the Duke of Chandos played a conspicuous role on a number of levels. Shaftesbury and Richardson were his contemporaries and friends and it is clear that he read their work, participated in debates and formed his collection accordingly. He was also a reluctant, but central figure in one of the century’s most notorious and public debates concerning taste and conspicuous consumption. This debate saw him identified as the epitome of luxury, the extravagant and tasteless figure of Timon in Alexander Pope’s poem Of Taste (1731). A study of the Duke of Chandos’s collecting and patronage is therefore situated at the heart of contemporary concerns about the right way to spend money.

Developing in parallel w...