Introduction

This chapter is about contemporary Warlpiri mortuary rituals performed immediately after a death has occurred, called ‘sorry business’ or simply ‘sorry’.1 The data on which this chapter is based is primarily derived from research at Yuendumu (a settlement of approximately 800 Warlpiri speakers, located 300 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs), as well as from participating in sorry business at a number of other Warlpiri settlements throughout the Tanami Desert.

In late 1998, I began doctoral fieldwork at Yuendumu with the aim to research everyday settlement life by looking at mobility and residence patterns. I specifically intended not to focus on ritual. When I arrived at Yuendumu, people asked me what I had come to do and I explained I wanted to learn Yapa way, the way in which Warlpiri people live and think about life. In that case, I was told again and again, I had better go to sorry. ‘You want to learn Yapa way, you go to sorry’, I was told, and ‘sorry business is Yapa way’. I was hesitant at first to participate in mortuary rituals, not only because this was ritual after all, but also because I thought it was not my place to do so, considering that it involved people grieving the deaths of people I often did not even know. Nevertheless, following the requests of the people I was living and working with, I came to regularly participate in sorry, driving my Toyota as part of large convoys to sorry business at other settlements, staying in ‘sorry camps’, and helping people in those camps with water, firewood and transport. Only retrospectively did I realize that my Warlpiri co-residents and myself actually spent about a third of our time involved in sorry – underscoring dramatically the fact that, today, Warlpiri communities experience so many deaths that sorry business is now an elemental everyday experience, or, as people say: ‘sorry business is Yapa way’.

The contemporary situation contrasts starkly with earlier reports, for example, from those of two key anthropologists who worked with Warlpiri people before me, Nicolas Peterson (I refer here to the work he did with Warlpiri people in the early 1970s) and Mervyn Meggitt (who worked with Warlpiri people in the 1950s). Neither witnessed mortuary rituals during their fieldwork – because nobody passed away when they were there (Meggitt 1962, 317; Peterson, personal communication, 2002). Accordingly, their analyses of Warlpiri life and Warlpiri ritual differ from mine. Meggitt only briefly discusses mortuary rites, relating them to the life-cycle and the roles and responsibilities of matrilines. In his comparative study of ritual in the central Australian desert and the tropical Top End, Peterson concluded that Warlpiri ritual had an explicit focus on fertility while people in Arnhem Land concentrated more on the management of death, seeing these emphases as reflective of their contrasting ecological zones:

Unlike the Murngin clan rituals, those of the Walbiri do not focus on death but on fertility. […] The concern of desert ceremonies with fertility would appear to correlate directly with the environmental differences between Arnhem Land and the desert (Peterson 1972, 22).

Speaking of Pintupi people, who live just to the south of Warlpiri, Myers (1986) makes a similar point. Contrasting Yolngu organization of structured alliances with realities in the desert, he says ‘among Western Desert people, social attention to temporal continuity in terms of mortuary, clan structure, or even the reproduction of alliances is insubstantial’ (Myers 1986, 295–6). These assessments of mortuary rituals and their significance to the structural organization of ritual, social and everyday life need to be reappraised in the light of contemporary realities.

The dramatic change from the infrequency of mortuary rituals during Meggitt’s and Peterson’s fieldwork (in the 1950s and 1970s) to the chronic occurrence of sorry business during my own fieldwork (since 1998) frames this chapter. My particular concern lies with the impact of high death rates and consequent increased frequency of sorry on contemporary Warlpiri sociality, Warlpiri personhood and Warlpiri bodies. In illustration, I compare certain elements of sorry with other Warlpiri ritual; and transcending the analysis of Warlpiri ritual in particular, I engage with some strands of the anthropological literature on mortuary rituals more generally. In regards to the latter, I focus on the roles and meanings of grief and joking in sorry. I begin with a short description of my first experience of sorry, and precede my discussion with an outline of the structure of contemporary Warlpiri mortuary rituals.

First Sorry

Early in 1999, news reached Yuendumu that an old man at Willowra (160 kilometres to the north-east of Yuendumu) was very sick. Some of my closest friends went to Willowra straight away and I did not see them until I arrived in Willowra with the Yuendumu contingent a week later, when the old man had passed away. A convoy of more than 25 cars, trucks and four-wheel drive vehicles left Yuendumu in the morning, and we stopped a few times on the way, once to cut nulla nullas (heavy fighting sticks), once for lunch, and once so the mourners could apply white ochre to their bodies. It was not until we reached the creek at Willowra that, there in the shade, one of the women came over to me. ‘You want to go sorry now?’ she said, and applied ochre to my face, arms and breasts; that is how I entered the sorry ground in the midst of my sisters from Yuendumu. Since the man who had passed away had been our classificatory son, we, the Napurrurla (women of a particular subsection)2 from Yuendumu, started the ritual by approaching the mothers of the deceased on the other side, that is the Napurrurla who had been at Willowra when the old man passed away. It was in a big mélange of bodies of wailing women embracing each other over a bedroll that I caught up with my friends whom I had not seen for a week. Many of them had self-inflicted head wounds, and the white ochre on our breasts was fusing with blood and tears. As we hugged and wailed with each other in turn, often individual wails were interrupted by a quick ‘Yasmine, good to see you’ – and I was very surprised to experience for the first time the intense mixture of grief, sadness, pain and joking that underlies sorry.

Sorry business is performed when an ‘adult’ Warlpiri person passes away; not for young children, nor for very old people.3 Sorry overrides all other concerns and the announcement of an adult death means that any ritual, work or other activity will be interrupted immediately. Generally most of the settlement population participates (again, with the exception of the very young and the very old), and the more prominent the person, the more in control of their life they were and the more unexpected their death, the larger participation will be, often involving the populations of a number of settlements. A large sorry business encompasses well over a thousand participants and may span a week and longer. The death of a Warlpiri person sets the following sequence of events in motion (which I here mainly describe from a woman’s point of view).

Announcement of Death

These days, most Warlpiri deaths occur away from Yuendumu,4 and a death usually is announced by a phone message which is then passed on from camp to camp following a formula of ‘bad news from X, Y doesn’t have a Z’; for example: ‘bad news from Alice Springs, Napurrurla got no sister’.5 From this moment onwards the name of the deceased is avoided in speech and replaced by the word kumunjayi (meaning ‘no name’, see also Nash and Simpson 1981). The deceased’s smaller possessions will be burned and his or her camp or house will immediately be deserted and henceforth physically avoided by all people close to the deceased. Such avoidance takes the forms of ducking in cars when driving past, re-routing paths through the settlement, and so forth. Upon receiving the message, women start wailing and walk towards the closest women’s camp (jilimi) in either East Camp or West Camp, two of Yuendumu’s ‘suburbs’ (see Musharbash 2003 on the spatiality of the settlement).

In the Women’s Camp

When arriving in the jilimi, women pass from one wailing person to the next, hugging them while wailing themselves, then they sit down and are in turn hugged by later arrivals. White ochre is brought out and ground with water on a flat stone. There are two different white ochres to be used for mortuary and other ritual respectively; the duller kaolin-based karlji for sorry and the shiny ngunjungunju for other ritual. Each woman applies ochre in an inverted U-shape over her temples and forehead, and most also cover their upper arms and breasts with it. This haphazardly self-applied, dull, white ochre in sorry signals differences from other rituals, where shiny ochres in different colours are bound with fat rather than water and are skilfully applied in beautiful patterns to one’s body by others (see Dussart 2000 for an analysis of ochres, body designs and notions of beauty in Warlpiri ritual). In the women’s camp, the following real and classificatory relatives of the deceased person cover their whole upper bodies in white ochre and shave off their hair: mothers, mother’s mothers and, in the case of a man, his wives, and in the case of a woman, her sisters-in-law (see Glowczewski 1983 for an excellent analysis of the role, meanings and significance of such shorn hair once it is made into hairstring and circulated). Within the context of the ritual, these women are considered key mourners. On the men’s side, these are the mother’s brothers, fathers, husbands and brothers-in-law. Men, however, do not shave off their hair.

First Sorry Meeting

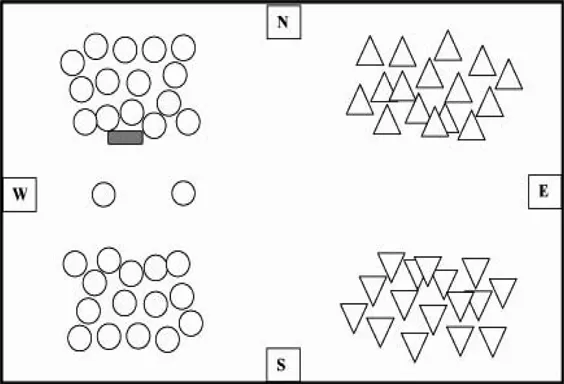

Once these preparations are well under way, people start moving towards the sorry ground at the outskirts of the settlement. There, people sit in four distinct groups waiting for everyone to arrive: men on the eastern side of the sorry ground (in two opposing groups, one to the south, one to the north) and women on the western side, mirroring the men. Associations of east with male and west with female permeate other domains of Warlpiri life as well.6

The women sit in groups of eight subsections on each side, with women of the subsection of the deceased’s mother at the front. If the ritual takes place on the sorry ground outside West Camp, the mothers sitting to the north (or, if on the sorry ground outside East Camp the mothers sitting to the south) are facing a bedroll.7 The ritual begins by the mothers from the other side walking towards the mothers with the bedroll, and, while walking, wailing and hitting themselves on their heads with nulla nullas, stones, tins, and so forth. Some women also employ women’s ritualized fighting steps, brandishing their nulla nulla in front of them. Women from the deceased’s sister’s subsection direct the walking mothers to the sitting mothers and prevent the worst self-harm. When the two groups of mothers meet, all the women kneel and each woman from the one side hugs each woman from the other side over the bedroll, while wailing. Then the mothers who walked over return to their side, and the sisters now direct the next subsection group to come over and wail with the sitting mothers. Simultaneously, the sisters direct the walking mothers back to the side where the other mothers sit, to wail with the next subsection group, until each of the eight groups on the one side has wailed with each of the eight groups on the other side.

On the eastern side of the sorry ground, the men also approach each other, albeit in quite a different manner. They use a stylized prancing step, brandishing spears and fighting boomerangs high up in the air. And while women are organized by subsections, men are organized into matrilines.8 Men’s style of wailing is different in tone, rhythm and pitch to that of women. Their body designs are also quite different: the men’s are painted in an extended V-shape, starting on the arms and shoulders and meeting around the navel. Lastly, men’s and women’s paraphernalia (boomerangs and nulla nullas respectively) and self-inflicted injuries differ significantly: women tend to gash their heads and cut off finger joints, while men gash their thighs (see also Meggitt 1962, 319–30).

When all groups on both the women’s and the men’s side have completed these actions, the spatial divisions between subsection groups and genders dissolve. Warlpiri people do not believe in natural causes of death, and every death for which sorry is performed must be avenged. Individual women close to the deceased approach the deceased’s mother’s brothers, now sitting in the middle of the sorry ground, kneel behind them, hug them and wail. The mother’s brothers are the ones to avenge the deceased’s death and the women’s action urges them to do so (see Meggitt 1962, 319–30 and Glowczewski 1983 for more details on the roles of mothers’ brothers during Warlpiri mortuary rituals). Around them, depending upon circumstances, people either leave the sorry ground peacefully – or (and more commonly) violence flares up and people from different families start making accusations and counter-accusations, hitting each other over the head and otherwise attacking each other, while screaming and ducking away from boomerangs flying from all directions. Such fights might be isolated to the particular death or, depending upon the circumstances of death and the relationships between families at the time, they might broaden out and incorporate into them expressions of anger and aggression relating to other fights. Eventually, with the latest occurring at nightfall, fights quieten down for the day and people leave for home or the sorry camp. More often than not, however, the fights flare up again during the remainder of sorry, and in other circumstances, often for years to come.

Sorry Camp

Following the reception of the ‘bad news’, all residents from the deceased’s former camp or house, as well as any close relatives and other classificatory key mourners who lived elsewhere, set up a sorry camp outside the settlement. After the first sorry meeting, more people move into this sorry camp (and more people will join them after subsequent meetings). Residency in sorry camps symbolizes the key mourner...