![]()

1 Juvenile

`...his childhood was sharply severed. It lodged in him whole and entire.'

Virginia Woolf, The Moment and other essays

In a letter of condolence to Henry Sinclair dated 22 March 1879 Lewis Carroll described the death 'of my own dear father', which had occurred over a decade earlier in June 1868, as 'the deepest sorrow / have known in life'. Despite this affirmation of his close feelings for his father, Carroll's biographers have painted an altogether more complex picture. Karoline Leach likened the son's mind to mercury, his father's to granite (1999, p. 101) and characterised his effect on the rest of his children as 'hyper-passivity' (p. 97). Mercury and hyper-passivity are not natural bedfellows, but nevertheless Leach detects that in later life Carroll 'even began to adopt certain aspects of his dead father's persons, echoes of the man's pomposity, a humourless sententiousness that had previously been alien to him' (p. 222). Morton N. Cohen also addresses the father-son relationship and identifies 'two forces in Charles's life that were working at cross-purposes: filial devotion and filial rebellion' (1995, p. 329) and poses the question: 'What did the father think of his eldest son?' (p. 340).

The facts of Charles Dodgson's life are succinctly summarised by Ivor LI. Davies in his Jabberwocky (1976) article 'Archdeacon Dodgson':

Charles Dodgson was born in 1800 at Hamilton in Lanarkshire. He was educated at Westminster School and Christ Church, Oxford, where he took a double first in classics and mathematics and obtained a studentship. In 1827 he married his cousin, Frances Jane Lutwidge, by whom he had eleven children, Lewis Carroll being the third. He became Perpetual Curate of Daresbury in Cheshire (1827), Rector of Croft in Yorkshire (1843), Canon of Ripon (1852) and Archdeacon of Richmond (1854). He died in 1868. (p. 46)

Born on 27 January 1832 Lewis Carroll, or Charles Lutwidge Dodgson as he was christened, therefore spent the first eleven years at Daresbury, where, according to his nephew and first biographer Stuart Dodgson Collingwood: 'Mr Dodgson from the first used to take an active part in his son's education' (1898, p. 22). Mrs Dodgson was also involved, as her son's small notebook chronicling his reading with his mother reveals.1 According to this he read Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress in February and March 1839 and went on to The Cheapside Apprentice, in which Anne Clark notes the extreme disrepute of the theatre (1979, p. 16). Whilst his young son was engaged in this purposeful reading, Dodgson senior was immersed in what was to be the most monumental undertaking of his entire life.

Dodgson was an exact contemporary of Edward Bouverie Pusey (1800-1882) with whom he had been at Christ Church. Pusey became Regius Professor of Hebrew at Oxford when he was only twenty-eight and thereafter took a prominent part in the Oxford movement, contributing to Tracts for the Times and aligning himself with Newman's controversial Tract XC (1841) (Donaldson, 1902, p. 149) after which he (Pusey) assumed the leadership of the movement. Dodgson was what was widely known as a 'Puseyite'; that, together with his undisputed ability as a classical scholar, led to him contributing to Pusey's ambitious series 'The Library of the Masters' which he had devised with Newman. Pusey himself edited the first volume St Augustine's Confessions, which appeared in 1838 with a further forty-seven volumes to follow, the last in 1885, three years after his death. As Pusey's biographer, Maria Trench, observed: 'The task of finding translators, editing, and writing prefaces to translations, was no light one', though it was no doubt ameliorated by the 'increasing sales', rising from 800 at the outset to 3700 in 1853 (1900, p. 105). How much say Dodgson had in the allocation of the volume with which Pusey entrusted him is not at all clear, though as Morton N. Cohen remarks he 'could not have undertaken so massive a labor...had he felt no sympathy for Tertullian' (1995, p. 324), for his lot was Tertullian (cl50-230), whom Cohen describes as 'a second-century pagan who converted to Christianity, lived an exceedingly ascetic life, and preached strict personal discipline and restraint in all things'. It was to this stern father of the Latin Church that Dodgson devoted much of his time, surrounded though he was bv his ever-increasing young family.

Of all the activities in which Tertullian counselled personal discipline and restraint none loomed larger than the theatre, launching as he does (in De Spectaculis) what Jonas Barish calls a 'systematic onslaught...against the frequenting of the shows by Christians' (1981, p. 44). Tertullian knew whereof he spoke since he had regularly attended such spectacles in his youth. Tertullian did not confine his objections to the undeniable degeneracy of many such performances, but went further and asserted the innate evil of all such activities. As for acting it involved 'an escalating sequence of falsehoods. First the actor falsifies his identity, and so commits a deadly sin. If he impersonates someone vicious, he compounds it...' and so on (o. 46).

Sadly for any aspirations Dodgson might have had for the lasting value of his translation Barish does not use it, though to do so can of course be revealing about the translator, who inevitably makes his own presence felt through his choice of words and overall tone. In his preface Pusey refers to the 'exceeding difficulty' of the translator's task in view of 'the condensed style of Tertullian', which in places had necessitated the sacrifice of 'his own ideas of English style'. But Dodgson had remained his own man: 'The Translator has purposefully abstained from the use of any previous translation, in order to give his own view of the meaning unbiased.' (Dodgson, 1842, pp. xvii-iii) The footnotes are of course Dodgson unalloyed, such as the following example which occurs early in the (for us crucial) section 'OF PUBLIC SHOWS': 'in like way in Greek, "the phrenzied pleasures...of the theatre'" (p. 188) as well as the circus and such like. In the passage about scriptural justification for condemning plays Tertullian had cited Psalm 1 verse i, which Dodgson renders: 'Blessed is the man, saith he, who hath not gone into the council of the ungodly, and hath not stood in the way of sinners, nor sat in the seat of pestilences' (p. 191). Dodgson deftly observes 'yet Divine Scripture hath always a wide bearing...so that even this passage is not foreign from the purpose of forbidding the public shows' (p. 192), a recurrent and unacceptable feature of which was 'immodesty' (p. 207): 'Thou hast therefore, in the prohibition of immodesty, the prohibition of the theatre also...tragedies and comedies are originators of crimes and lusts, bloody and lascivious, impious and extravagant' (p. 208). Dodgson certainly seems to be entering into the spirit of the original here as he does in another key passage: 'we fall from God...when we touch aught of the sinful things of the world. Wherefore, if I enter the Capitol, or the temple of Serapis, as a sacrificer or a worshipper, I shall fall from God, as also if I enter the Circus or the theatre as a spectator.' (p. 198) The ban, it is important to note, is total. There is no discretion, no distinction between good and bad, moral and immoral plays:

The Heathens, with whom there is no perfection of truth, because God is not their teacher and truth, define good and evil according to their own will and pleasure, making in one case good, which in another is bad, and that in one case bad, which in another is good. (p. 210)

These were to be abiding concerns for Lewis Carroll who, despite spending his early years under the same roof as his father who was translating one of the most virulent anti-theatrical texts ever written, became an inveterate theatregoer. Fifty years after the publication of Dodgson's translation of Tertullian, Lewis Carroll wrote to A. R. H. Wright on 12 May 1892 that 'we ought to abstain from.. .all things that are essentially evil', from which he excluded the theatre: 'I take them [his young friends] to good theatres, and good plays; and I carefully avoid the bad ones'. And on the subject of pleasure he wrote to Ellen Terry on 13 November 1890 clearly with the theatre in mind:

The 'selfish man' is he who would still do the thing, even if it harmed others, so long as it gave him pleasure: the 'unselfish man' is he who would still do the thing, even if it gave him no pleasure, so long as it pleased others. But, when both motives pull together, the 'unselfish man' is still the unselfish man, even though his own pleasure is one of the motives! I am very sure that God takes pleasure in seeing his children happy.

Sure though the adult Lewis Carroll was that 'God takes pleasure in seeing his children happy', it is uncertain how much as a child he was on the receiving end of such an attitude from his own father. Indeed Carroll's dedication to giving such pleasure to children and - belatedly - to himself might very likely have been in compensation for what he had experienced - or rather not experienced - in his own childhood.

Through Dodgson's translation of Tertullian and his son's letters the two engage in a virtual debate about the theatre across the decades. Whether they engaged in such a debate face to face, and if so when, can only be speculation. Violet Dodgson, the fifth daughter of Wilfred Longley Dodgson and therefore Carroll's niece, recalled her grandfather as 'a dignified but genial man' whose presence at dinner ensured 'an amusing and exhilarating evening': 'He had a great fondness for a good argument and plunged, good-humouredly but eagerly, into controversy. So did his sons after him and Charles not least.'2 Of his position in an argument about the theatre Violet Dodgson was in no doubt: 'the Archdeacon, though allowing private theatricals and charades, set his face against theatre-going and none of his 7 daughters ever went inside a real theatre'. Such an attitude was by no means unusual. The Revd Stewart Headlam, from whose advocacy of the music hall - as well as the theatre Carroll dissented, grew up in an evangelical family at Wavertree, near Liverpool with his father Thomas, 'a great hand at charades', who completely proscribed attendance at theatres (Bettany, 1926, p. 6).

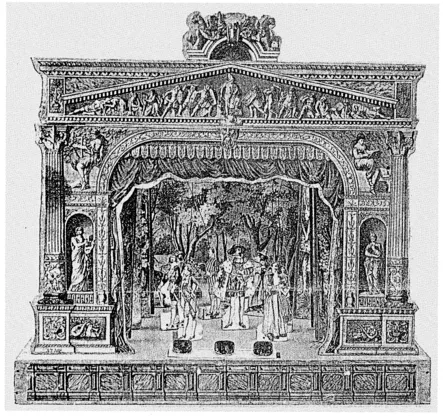

Another dispensation from the Revd Charles Dodgson was also very typical of such families at the time: a toy theatre, made, according to family tradition as vouched for by Collingwood (1898, p. 28) and Violet Dodgson, by Lewis Carroll 'with help from the village [Croft] carpenter'. As George Speaight has shown, Juvenile Drama in the form of printed sheets depicting the theatre, characters and scenes (as published by Robert Dighton, Hodgson and Co. and Skelt) to be cut out and assembled 'was in its origins and in its heyday entirely pre-Victorian and mainly Regency in character' (1946, p, 60). Lewis Carroll's theatre at Croft obviously belonged to a later generation, in George Speaight's opinion it 'must be one of the very earliest German stages to have reached England' (p. 157), though as he acknowledged it would have been considerably earlier than any other known example. If anything the uncertainty was increased by the evidence provided in 1928 by Mrs Marion Parrington, described as a distant cousin, who wrote to Louisa Dodgson, the last surviving sibling of Lewis Carroll, about a toy theatre which had been passed on to her twenty-seven years earlier and was 'a quaint shabby old thing these days...[it] must be 70 years old, the funny figures with long wires, in their old fashioned clothes are so amusing they all have their names on the back'/3 What Mrs Parrington was trying to do was to obtain family approval for her intention to sell the theatre, which she proceeded to do at Sotheby's on 14 November 1928 when it was bought by one John Cresswell Brigham for £10, He displayed it in his private museum in Darlington. According to Florence Becker Lennon it was shown at a centenary exhibition in London in 1932 (1947, p. 321). Thereafter any trace of the theatre disappears, but interest was aroused by a short report in The Times (10 October 1972) which included a tiny reproduction of a photograph, which had originally appeared in the Queen magazine (18 November 1931) on the basis of which Mrs Dodie Masterman 'identified the theatre as made up from engraved sheets published by Adolf Engel...in about 1880!' (Crutch, 1973, p. 3). Clearly this now apparently lost theatre could not have been that used by the young Carroll.

The idea of Carroll constructing his own theatre with the village carpenter is in any case rather more appealing, but the important thing is that he indulged in this pastime when it was hugely popular, not only as a hobby, but also professionally. George Speaight has researched the Royal Marionette Theatre, located off the Lowther Arcade in the Strand, where in 1852 Signor Brigaldi directed puppets 'from the theatres at Naples, Milan, Genoa etc.' accompanied by 'their own orchestra' (1955, p. 240). In total Brigaldi had about 150 marionettes, each between two and three feet high made of wood, cork and papier mache. They were manipulated from a high bridge. The pieces in which they performed were burlesques or parodies, which satirical though they often were evaded censorship because they were performed by puppets. The marionettes were very much the vogue. Their season ran for six months until July 1852 after which they toured the provinces spending three months in Manchester and two in Liverpool. They returned to London and 'were eventually established at Cremorne Gardens in 1857 in a magnificent Marionette Theatre, with an imposing Italianite fagade, capable of seating a thousand people which had been specially built for them' (p. 242). Cremorne Gardens had previously hosted a rather more modest marionette installation in 1852 when they were 'great favourites of the public and of the proprietor, who liked "the little beggars who never came to the treasury on Saturday'" (Wroth, 1907, pp. 7-8). As Henry Morley observed: 'Puppets have at various times, therefore, and in various countries, had a larger following than one might have thought fairly due to the merits of wooden actors in the abstract. Wooden actors in the concrete (flesh and blood) have been so much worse.' (1891, pp. 28-9)

Marionette theatres clearly appealed strongly to large numbers of adults principally as spectators, but whereas there is no evidence of Carroll attending such performances, though he must have been aware of them, there is evidence of him still working with his own theatre in the summer of 1855, when he was twenty-three. George Speaight has written: 'The early Toy Theatre was, in fact, never intended for children, in the sense that paper toys were. It was quite obviously intended for the enthusiasts of the theatre, who were mainly young men and boys; and it was the boys who insisted upon making the thing work, and compelled its evolution from souvenir sheets of characters to complete plays.' (1946, p. 119) Speaight is of course referring to early nineteenth-century toy theatres for which, as we have seen, he adopted the term 'Juvenile Drama', but the point about the appeal being to 'enthusiasts of the theatre...mainly young men and boys' may have had equal - or greater application to the more complicated mid nineteenth-century toy theatres. That Lewis Carroll's continuing fascination with his marionette theatre was not all that unusual is evident from the fact that it was shared by his cousin, Charles Robert Fletcher Lutwidge, who, being three years his junior, was twenty in 1855. On 9 July Carroll wrote in his diary of his activities helping at the new National School at Croft, adding 'Fletcher has been here since Friday'. He refers to Fletcher again on 13 July: 'Fletcher still here. During his stay he painted one scene, a palace interior, for the Marionette theatre. I am convinced now that calico is the best material for painting on.' For Fletcher this was valuable experience for his contribution to ADC productions at Cambridge as F. C. Burnand recorded:

Mr. Gage was the local paid artistic talent, but in the year 1857 Charles Lutwidge, of Trin Coll., painted a proscenium for us, representing the figures of Tragedy and Comedy standing in niches under the busts of Shakespeare and Moliere. A scroll ran along the width of the proscenium with the motto 'All the world's a stage', and the club initials, 'A.D.C.', in the centre. The same amateur artist also painted for us 'the conservatory flat' in Still Waters - a very effective set-piece - and some other set-pieces for the burlesque of Turkish Waters and Lord Lovel. He had also commenced a design for an act-drop...

As we came to depend more on ...