![]()

Chapter 1

Theoretical Basis of Land Value Taxation

Willian J. McClucksey with guest authors Owiti A. K’akumu and Washington H.A. Olima

Introduction

Tax is a compulsory payment, usually of monetary form, made by the general body of subjects or citizens to a sovereign or government authority. It has the following special characteristics:

- it is paid without quid pro quo;

- it is enforceable in law;

- it may be levied against persons (natural or corporate); and

- it may also be levied against property.

Our primary concern here focuses on the last aspect i.e. taxes levied against property and in particular landed property. Indeed, we are not concerned with landed property per se. The scope here is limited to tax operations that are meant to capture land value. But taxes that are levied against property are not the only taxes that would capture land value. Even taxes levied against persons would at times capture land value as will be discussed later in this chapter.

Some requirements for a good tax structure

Adam Smith (1776) and Musgrave (1989) have identified some prerequisites for a good tax system. The following broad requirements are generally associated with a good tax:

- the distribution of the tax should be equitable, in other words every taxpayer should be expected to pay a fair share of the tax (i.e. the Canon of Equity);

- the tax structure should endeavour for fair and non-arbitrary administration. It should also be understandable to the taxpayer (i.e. the Canon of Fairness);

- when compared to the revenue collected, the administration and compliance cost of a tax should be as low as possible – in other words it must be economical to collect (i.e. the Canon of Economy);

- tax obligations should be based on benefits receivable from the enjoyment of public services (i.e. the Benefit Principle);

- tax should be levied at the time, or in the manner which is most likely to be convenient for the taxpayer (i.e. the Canon of Convenience);

- taxation should as much as possible avoid creating ‘excess burdens’ that would interfere with the efficient functioning of the host market.

The above conditions for a good tax system were meant to apply to taxes in general and therefore also with regard to property and land taxes.

Although taxes could also be used as instruments of socio-economic leverage, or for achieving various other non-fiscal goals, due care should be taken not to deviate from the above-stated principles for a good tax. In this context it is noteworthy that land taxes are quite often suggested as useful instruments to assist with land redistribution and/or land reform programmes.

The historical concept of land value taxation

Put at its simplest the concept of land value taxation rests upon the premise that only land should be taxed. As Youngman (1993) puts it, even this simple idea can create major difficulties in political acceptability and administrative limitations. In any society, there are three classical factors of production, land, labour and capital. The latter two have their costs and therefore their prices in terms of wages and interest. On the other hand, land has no cost of production, and if land was in unlimited supply people would pay little or indeed nothing for its use. However, land is not unlimited in supply, it is quite the opposite being fixed in supply. This fact creates demand for land in particular locations and therefore a value of land. Whilst land is generally accepted to be fixed in supply, the concept of alternative uses can create a supply shift, in that, supply for one kind of use rather than other kinds follows its own supply versus rent curve to the point where supply and demand equalise. The rent for land is said to constitute two components, firstly, its transfer or opportunity cost, which is the rent of the land in its next best use. Secondly, an amount attributable to scarcity or inelasticity of supply for a use in a particular location. It has been recognised that land was a free good as opposed to labour and capital that are never free. Therefore the market price of the products of land is determined by the cost of labour used in their production and capital equipment. On this basis the amount remaining for distribution as land rent is an excess (Lindholm, 1965; Douglas, 1961)

The history and economic foundations of land taxation are firmly rooted in the early 18th and 19th centuries. The Physiocrats argued that a particularly unique way to raise revenue was through the taxing of land (Quesnay, 1963 (1756)). Their belief in the sterility doctrine gave rise to the theory of ‘impost unique’. Taxation of land was justified because of the productivity of land. From a social standpoint, therefore, the taxation of land had positive benefits. This group of economists tended to the view that since all taxes had to be paid out of rent, it would be sensible to replace all other taxes by a single tax on rent. In many respects the work of the Physiocrats laid the theoretical foundations that subsequent economists would construct their theories of land taxation. Smith (1776) famous for his canons of taxation made a number of important contributions to the land tax debate differentiating the land tax between a tax on agricultural land and a tax on ground rent to cover developed land. He found land to be suitable for taxation, since the tax would fall on the economic surplus and as such could not be passed onto consumers in the price of goods.

Ricardo (1817) suggested that the rent for land be the residual after paying for the costs of variable factors of production. His theory was largely based on the premise that a tax on land rents would not have harmful effects of the economy as such a tax would not inhibit production. Ricardo’s theory was taken further by Mill (1824) who explained that a tax on the rent of land would not affect the industry of a country. In this regard he contended that as the cultivation of land was dependent upon the investment of capital, the capitalist was to some extent indifferent as to whether he paid the surplus, in the form of rent to an individual, or a tax to the government. Following on from his father’s work Mill (J.S.) (1848) suggested that if the rent of land increases as a result of society, the owners of the land should have no claim to this ‘windfall’ increase in land value. The difficulty with this approach is based on the issue of clearly linking the increase in value to some identifiable societal improvement.

Henry George (1879) set out his views on the taxing of land (the ‘single tax’) in some detail in his book, Progress and Poverty. George was influenced by the state of the economy of the time and in particular, how development and progress in society was accompanied by high levels of poverty. His explanation of this phenomenon centred around the scarcity of land which was as a result of land speculation. The solution proffered by George was to replace all taxes with a single tax on land. This would have the desired result of making land more accessible to a greater number of people, raise wages, lower prices and in consequence raise the living standards of workers. In this regard, an increase in land values would be due to increased productivity which was closely related to increases in population and wealth. This rental income gave land its value and as such could be collected in taxes without decreasing the incentives for efficient production (Lindholm, 1965).

Proponents of land value taxation have cited a number of appealing properties, one of the main ones being its neutrality with respect to land use (Bentick, 1979; Tideman, 1982; Wildasin, 1982, Tideman, 1999). As Netzer (1966) argues, location rents constitute a surplus, and taxing these rents will not reduce the supply of sites offered, provided that landowners have been optimally using the land prior to the imposition of the tax. Economic theory also shows that under the assumption of perfect markets, a tax on any good with perfectly inelastic supply and non-zero elasticity of demand will be borne entirely by the supplier of the good; it cannot be shifted to its user because any increase in the price would lead to an excess supply of the good (in a competitive market the demand for units that are offered at a price above market price will drop to zero). Therefore, a tax on land has to be paid by the owner of the land (Skaburskis, 1995). Given that the supply of land is fixed, the tax does not have any substitution effect and therefore no deadweight loss, which makes it an ideal tax from an efficiency point of view. It is also argued that the real property tax (a tax on both land and improvements) has a number of negative economic effects on investment decisions (Mathis and Zech, 1982). It is alleged to discourage improvements to a site by reducing the economic return from such improvements. This reduction, in turn, results in a disincentive to maintain and improve buildings, the substitution of land for capital, causing urban sprawl, the utilization of buildings beyond the point at which they should be replaced and the speculation in land by holding it off the market. Advocates of land taxation argue that removing the tax on improvements and taxing only the value of the land would result in a restoration of the incentive to develop land to its fullest potential.

Ever since the publication of George’s Progress and Poverty in 1879, the possibility of using land value taxation as a source of government revenue has intrigued economists and other tax specialists. The impact of George’s ideas, whilst not widespread in a geographical context did effect the politicians of the day in New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Jamaica and Kenya to introduce such a tax. Indeed, graded property tax systems, where land is taxed at a higher rate than improvements have been used in several Canadian provinces as well as several cities in the United States (Oates and Schwab, 1995; Brueckner, 1986; Wuensch et al, 2000).

The concept of land value

Classical economists have identified land, labour and capital as the three factors of production (Vickrey, 1999). Under ‘capital’ was implied all means of production that have been created through human effort while ‘land’ was primarily used to describe natural resources that were not created through human effort.

Land value in turn refers to the earnings accruing to land in the process of production. Where land is not put into productive use, the value will be based on the opportunity cost of not putting land in the production process. ‘Opportunity cost’ here refers to the next best alternative use that land could be put to. These earnings may be realized in loose form and expressed as rental income/value, for example annual, quarterly, monthly, weekly or daily rent. The earnings may also be realized in compact or discounted form and expressed as capital value. The capital value is the basis upon which the exchange price of the land will be considered. Land value therefore refers to a stream of income from land as a factor of production considered under a certain or definite period of time. Value in this case is tied to the income generating advantage of land. However, even land that is not put in the income generating process will still have its value derived on this basis by relying on the concept of opportunity cost. Opportunity cost would be subject to the prevailing land market conditions.

As a factor of production, land like any other commodity, is traded in the market. This means that the price (value) of land will be subject to the economics of demand and supply. In this respect, land becomes a unique commodity since it has unique demand and supply descriptions. Indeed, as a discipline, land economics is based on two basic concepts, namely:

- that the supply curve of land – as a commodity – is perfectly inelastic; and

- that the demand for land is derived demand.

Land is fixed in terms of geographical location. For that matter, all economic advantages provided by land must be utilized on site. Location is therefore crucial in determining land values because shortage in supply at one place cannot be made up for by surplus at another place. The value of land will be influenced by those economic factors pertaining to the area in which it is situated.

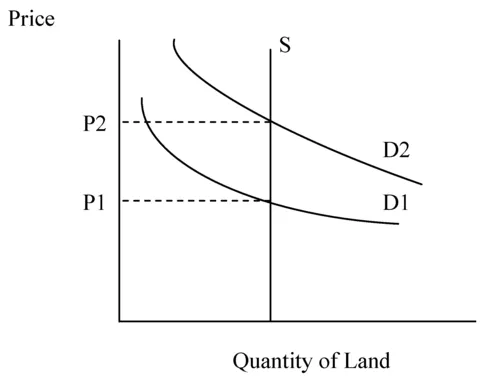

The immobility of land in turn influences its economic characteristics. Just as the land is fixed in geographical location, its supply too is generally considered as fixed. Because the supply of land is fixed, in theory, its supply curve is perfectly inelastic. This means that increases in the price of land from P1-P2 (as shown in Figure 1.1) arising from a shift in the demand curve from D1-D2 will not stimulate an increase in supply. The supply will remain the same no matter what the price increase is. This particular fact applies for land as a gift of nature that cannot be created by efforts of man. It also applies for land that has undergone capital investment by man. Some lands are uniquely developed to the extent that their supply is inelastic. For example, no matter what prices are offered for Fort Jesus in Mombasa, Kenya or the Pyramids in Giza, Egypt, there would be no increase in the physical supply of such lands. In theory, at least, this applies to all lands with only limited variation.

Figure 1.1 Demand and supply of land

The supply characteristics of land, as discussed above, have a significant impact on the levying of land value taxes. These taxes are levied on the assumption that they would not interfere with the supply of land and hence cause no disruption of the economic equilibrium. In practice, however, the supply of land for a particular use in a given area may change in the long run as more land is brought into that use. Even in the short run, land can be transferred within limits from one use to another, for example, through rezoning (e.g. converting a residential house to office space).

The demand for land, as such, is purely derived demand. Land is not demanded for its own sake, but virtually as a factor that is used for the production of goods and services. The demand for land will therefore depend on the demand for goods and ser...