![]()

Chapter 1

The Challenge to Theology

Theology today ought to be contextual theology.

This thesis moves us immediately into the centre of the ongoing debate about whether theology is necessary in the so-called postmodern society? If the answer is yes, is there only one correct way or several different equally correct ways of approaching theology? How is it possible to model theology with universal claims of validity? How do different conditions of social, cultural, historical, and ecological nature influence meditation over the meeting with God?

These questions keep returning if one looks at the list of publications in academic and theological debate. Several possible answers may be discerned. The same questions occur in the pastoral sphere as well. Here we have discussions about issues like, the process of self-examination in the Swedish Lutheran church, the Roman Catholic world catechism, theology of liberation and the validity of feminist theology, all of which show a fragmentary, changeable, and conflict-filled picture of standpoints.

In Sweden, one question has been posed for a long time: is it at all possible to draw any relevant conclusions about the belief in God as a shaper of society? The question is whether the claims of theology convince others than those who have already found salvation? The result is that many members of the clergy and theologians either retire to exclusively confessional language or prefer arguments, supposedly shared by all mankind, about theology. A simple solution is to switch between the two languages: to talk religiously about and to God with confessors and to talk generally about God with others. Whether a naturalistic or an economic outlook on the world is considered, the humanist’s perspective on life will be as problematic as the perspective of the Christian faith when related to the development of the postmodern image of the world.

This means, is it possible to meditate on God in the middle of different events in life or should this only be reserved for confessions behind closed doors? Where and how will a theological text become meaningful? Should one promote a non-confessional language for the Christian faith?

This first chapter summarizes the reasons which support the argument that theology ought to be contextual in today’s post-modern society. First, I will outline the meaning of the notion and its history and define the difference between “contextual” and “non-contextual” theology. Then I will give six reasons for contextualization of the Christian interpretation of life. “To contextualize” means to heighten the consciousness of the significance of the context of thinking and acting.

What is “Contextual Theology”?

“Context” is an immigrant from philology. It refers to that which surrounds (Latin con-) a text. Context means the parts of a text that precede and follow the text in question and which are of importance for its understanding.

The words “time (Greek kairos) is now” are preceded, for instance, in the Gospel of St Mark by the information about the arrest of John the Baptist and Jesus’ voyage to Galilee. The narrative follows the text where the disciples are called to be fishers of men and women. The text about kairos has a context. It denotes a particular political situation where the prophet finds himself in conflict with the governing powers. The text is also inserted in a context of action from which arises the first fellowship around Christ. This is the foundation of the later church. The further context of this text is decided by the classical collection of texts “The Bible” which the young church’s canonical decision granted a normative function for the fellowship of faith.

The linguistic meaning of context can be transferred to other fields. Today the word also denotes the particular social, cultural and ecological situation within which a course of events takes place. A theological text, for instance, comes into being within a wider context, that is, it is determined by the traditions and circumstances that have an effect on the complex situation of the author and the reader.1 The text is also dependent on a connection with other texts. The meaning of the text originates in what can be termed “intertextuality”.

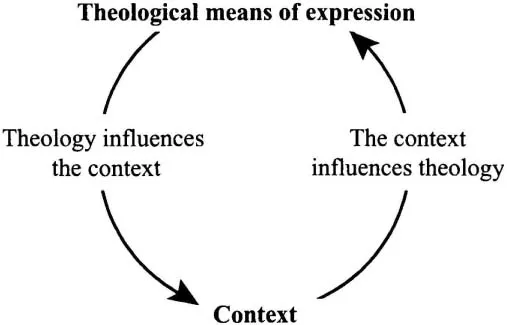

The text and the context interact in two directions. This can be modelled as the circle of function. The interpretation of Christianity’s shape and content interacts with a large number of factors in the context within which they are created.

The history of the notion of context is short. Two Asiatic theologians, Shoki Coe and Aharon Sapsezian, pleaded in 1973 for a contextualization of theology.2 They then demanded that the educational programme of the ecumenical movement should take place in context, that is, theological education should be brought into “the field” to a larger degree. Theology should be a living meeting between a universal Gospel and the specific reality where people are.

During the 1970s and 1980s a large number of programmed attempts were made where human experiences in particular situations were given a central function in theology. This was done without employing the designation “contextual theology”. Special attention was given to experiences of suffering and structurally conditioned repression.

The theology of liberation arose in Latin America as a people’s evangelization among primary groups. It was a reflection of the significance of faith in God for a people’s fight for freedom from an unjust dependence upon colonial powers.3 In black theology, theologians in Africa and the USA focused upon the experience of being black and marginalized.4 The Minjung theology in Korea brought the suffering people’s pain into theological focus.

Since then, feminist theology has treated the issue of how women and men will understand God’s historical and present revelation in a multi-faceted manner. This is in relation to biologically and socially constructed conceptions of gender. The latest addition is ecological theology, which since 1972 has grown as a theological reflection on experience by nature conservationist and urban green movements based on modern society’s destructive relations to nature.

In spite of contextual theology coming into being already in 1973, it was not until the 1990s that it was applied in relation to all these approaches. The notion of contextual theology today also functions as a means of gathering the theological approaches that emanate from a similar understanding of theology’s task and method. Contextual theologians are also noted for striving to interpret what I will call “the ongoing incarnation”. They have a unifying trait in that they depart from people’s specific experiences in their meetings with God in unique situations. The conditions that are clear beforehand, such as conditions of support, the physical space, the language, ways of thinking, form of culture, traditions, are given a leading and fundamental significance by contextual theologians in the interpretation of the acts of God.

We can therefore distinguish between two characteristics in the notion of contextual theology. First, it aims at a theological method. Contextual theology is an interpretation of Christian faith, which arises in the consciousness of its context. The interpretation of “God today”5 occurs in connection and in dialogue with people, phenomena and traditions in our age and the surrounding world. Contextual theology not only gathers the experiences that arise in specific situations. It also strives to actively change the context. In this way, theology becomes part of the process of cultural renewal. Text and context, theological and cultural contents and shapes of expression, all interact in two directions in a common circle of function.

Second, the notion indicates a group of attempts, which in different circumstances use and develop this method.6 The common traits in these attempts can be listed as follows:

– the significance of the subject’s specific experiences, in particular experiences of suffering and deliverance,

– the criticism of the theology of eternity and the confusion between local and universal claims to validity,

– the striving for social and emancipating relevance,

– the renewal of theological ways of expression in close collaboration with local forms of culture,

– the assumption of the unity of the world and history caused by belief in the Creation and a positive estimation of cultural and biological multitude in the wholeness of Creation.

“Contextual theology” also encompasses two different though related areas of action in the pastoral and academic spheres. The main figures in the church shape the rendering of the Christian faith in accordance with its context for pastoral theology. In academic theology, the main figures of science reflect upon connections between the rendering of the Christian faith and the context.

Apart from contextual theology, there are also discussions about contextualization, meaning a conscious process in which theology focuses on the importance of context.

Contextual and Non-Contextual Theology

Contextual theology is therefore understood as the interpretation of Christian faith which is conscious of the importance of the situation and connection for shaping the theology.

It is, of course, possible to opt for another definition and assert, for example, that contextual theology is different from universal theology. This would then make contextual theology into the kind of interpretation of the Christian faith that arises in a special context, for example, the poor in the Dalit caste in India or the Christian minority in China. Such a theology is considered to be completely determined by its context, which brings it into opposition with a universal theology, meaning an interpretation of the Christian faith, which is valid for all Christians in the world. Contextual would then mean being “determined by context” and its opposite would be “theology that is independent of context”.

The representatives of contextual theology claim, however, that every theology is determined by its context. This means that there are no universal theologies, which work independently of their context. Per Frostin claims that one should distinguish between interpretations of the Christian faith that are conscious of context and those that are not, rather than differentiating between context-dependent and context-independent.7

Robert J. Schreiter suggests that we should also distinguish between “local theologies” and “contextual theologies”. According to him, local theology indicates those interpretations of the Christian faith that arise among believers in a certain place. On the contrary, by using the notion contextual theology we focus upon a sensitivity for and consciousness of the importance of the social and cultural connections.8 In this way, different local theologies can be more or less sensitive to and conscious of the importance of context.

If by this we mean that every theology today must be contextual, it then signifies an inevitable demand upon the consciousness of the respective interpretations of the Christian faiths and their contexts. Whoever expresses a selection of statements of faith and asserts their normative value for others must be able to account for a number of questions. When, where and how have these dogma arisen? Which person or which persons have formulated them? For whom are they valid? Under which circumstances are they valid?

If we say that every theology today ought to be conscious of its context this does not mean that this is something completely new exactly in our time. We could rather assert that many interpretations of the faith in the long history of theology have been contextual. This is precisely because they are consciously attached to the prerequisites of the surrounding world and the actual period.

In the Christian tradition contextual theology already exists so it does not need to be invented. Albert Nolan has consequently formulated the thesis: “All theology is contextual”.9 The innovative aspect in this is that for him theology is no longer a study of God but a study of what God says and does in a context. According to Nolan, theology is rather a study of the context per se.10

Naturally, one could now argue that if theology always has been contextual there is nothing new in this. Is this simply just another and awfully complicated word denoting an old truth? If the purpose is known, why cannot we just let the matter rest?

This is certainly a matter of insight that our predecessors in the history of theology also must have experienced. There is no obstacle, though, to the need of being interpreted again. As we shall see, contextual theology to a very high degree lays claim to being in harmony with the Christian tradition.

Yet, there is often another string to this objection. The critic thinks that if it really does not contain anything new, there is no reason to change known methods of shaping...