![]()

Part I

Introduction and Background

![]()

Chapter 1

Objectives and Perspectives

Kathleen P. Bell, Kevin J. Boyle, Andrew J. Plantinga, Jonathan Rubin, and Mario F. Teisl

Introduction

Land is an input to the production of an array of private goods, including agricultural crops, forest products, and housing. Private decisions about the use of land, however, often give rise to significant external costs, such as non-point source pollution and changes to wildlife habitat, and external benefits, such as the provision of recreational opportunities. One role of land-use policies is to narrow the divergence between privately and socially desirable outcomes, either by altering the incentives faced by private agents or through direct government ownership and management of land.

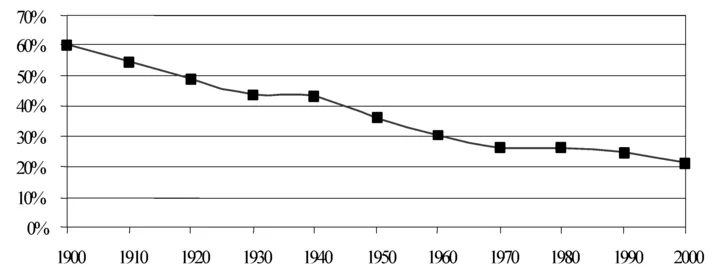

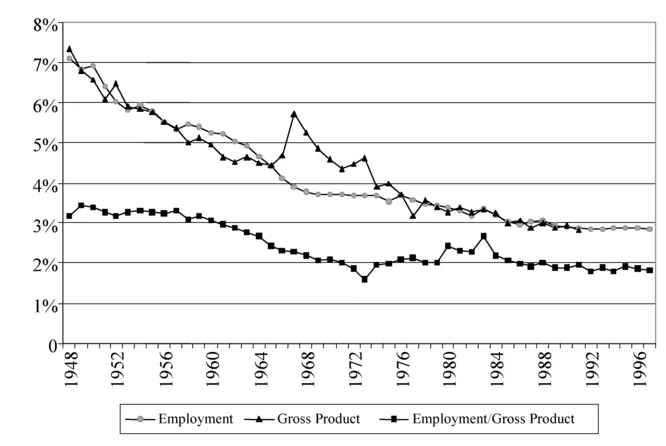

The rural landscape of the United States underwent tremendous changes during the 20th century, and these changes have given rise to complex and pressing land-use policy issues. As shown in Figure 1.1, the share of the U.S. population living in rural areas has decreased steadily since 1900. In 2000, approximately 21 per cent of the U.S. population lived in rural areas. Much of the employment in rural areas has traditionally been in agriculture and forestry industries, for which land is an essential input. For example, in 1820 approximately 70 per cent of the U.S. population was engaged in farming, while in 2000 only two per cent of the U.S. population was engaged in farming (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2000). Labor-saving technology, which has reduced the labor requirements in these industries, accounts for some of this decrease. Other factors, such as an absolute decline in farm income, are also responsible. Figure 1.2 shows an almost 33 per cent decline in employment per $1,000 of real gross product in rural land-based industries since the 1950s. In addition the relative importance of these industries to the U.S. economy has declined. Rural land-based employment and gross product, expressed as shares of U.S. totals, have declined steadily since the 1950s, although the rate of decline has diminished over time (Figure 1.2).

Paradoxically, while many rural areas struggle with problems of declining population and economic activity, other rural areas face problems with rapid population and economic growth. After World War II, there was a dramatic shift in population from traditional rural areas and urban centers to suburban areas. While many factors have contributed to suburbanization, including the availability of low-interest loans for new home construction provided to returning World War II veterans by the Veterans Administration, it is difficult to overstate the importance of affordable private automobile transportation and public road construction. In 1950, the U.S. population (152 million people) used 43 million cars and trucks to drive 458 million miles. By 1997, the U.S. population (now 268 million people) used 201 million vehicles to drive 2.5 billion miles (Davis 1999). Vehicular transportation was made possible by extensive road construction, including the expansion of the Interstate Highway System, under the Federal Highway Aid Act of 1956, by 3.9 million miles (U.S. Department of Transportation 1999).

Figure 1.1 Percentage of the U.S. population living in rural areas, 1900-2000

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census.

Suburbanization has resulted in the conversion of millions of acres of rural land near cities to developed uses (Vesterby, Heimlich, and Krupa 1994). According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, the area of urban land, which by the Census definition includes suburban areas, increased by about 120 per cent between 1960 and 1990. At the national level, urbanization has outpaced population growth, which increased by only 40 per cent during this period. The post-war migration to suburban areas dramatically altered settlement patterns in the U.S., such that by the 1990s a majority of Americans lived in suburbia (Carlson 1995). These shifts in population have changed the rural landscape from one that provides simultaneous production, economic livelihood and residences for a large percentage of the population to one that provides opportunities for urban and suburban dwellers to relax and recreate.

The impacts of shifting populations and changing landscapes have been documented for many regions of the United States. The repercussions of these transitions are different in rural and urban areas, and across regions. In Maine, for example, a recent analysis revealed that the fastest growing communities (in terms of the rate of population growth between 1960 and 1990) were, in most cases, on the outskirts of traditional city centers (Maine State Planning Office 1997). Over the same period, many of these city centers experienced losses in population. Against this backdrop of suburban migration the populations of more distant, rural parts of Maine have been declining. Between 1990 and 2000, four of Maine's sixteen counties, all located in the northernmost part of the state, experienced declines in population (U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census 2000).

Figure 1.2 U.S. rural land-based employment and gross product*, 1948-1997 *The employment and gross product series are full-time equivalent employment and gross product (value added) for Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) 01-02 (farms), 07-09 (agricultural services, forestry, and fishing), 24 (lumber and wood products), and 26 (paper and allied products), and are expressed as a share of the U.S. total. The employment/real gross product series is the number of full-time equivalent employees per $1,000 of real (1982=100) gross product for rural land-based sectors.

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis 2002.

The changing function of rural lands is also the result of a fundamental shift in public preferences regarding land use and the environment. Following the proposed construction of the Hetch-Hetchy dam in Yosemite National Park in the early 1900s, public land management emerged as a matter of public concern and debate. During the 1960s, 1970s, and continuing today, the increased demand for non-commodity benefits from public lands has forced a reassessment of management practices by federal agencies, such as the U.S. Forest Service, who have traditionally placed a primary emphasis on commodity production (Bowes and Krutilla 1985). Public preferences for non-commodity benefits were central to the spotted owl controversy in the Pacific Northwest. While arguments focused on spotted owl habitat, underlying currents of the debate included the presumed right of forest industry firms and timber-dependent communities to harvest timber on national forest lands, public demand for forest recreation unaltered by timber harvesting, and existence values for old-growth forest ecosystems. Similar controversies have arisen on both coasts of the United States related to the protection and management of native salmon stocks. In recent decades, public expectations regarding rural land use have expanded to include activities that occur on privately owned lands as well, as evidenced by citizen-initiated efforts to regulate timber harvesting in Maine. Georgia, Alabama, and other eastern states. Another notable trend in recent decades is the willingness of citizens to support government land conservation programs. For example, in 2003, voters in 23 states passed 100 ballot measures, leveraging almost two billion dollars for land conservation (The Trust for Public Land and Land Trust Alliance 2004).

A confluence of demographic, economic, and social forces has stimulated conflicts over the use of public and private rural lands and policy actions at federal, state, and local levels of government aimed at resolving these conflicts. In response to changing preferences for outputs from public lands, federal land-management agencies have given greater weight to non-commodity benefits in the management of public lands for timber, agriculture, recreation, and environmental protection. Federal programs, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Conservation Reserve Program, have put an increasing emphasis on achieving environmentally beneficial outcomes (Osborn, Llacuna, and Linsenbigler 1995). In some instances, federal policies regulating uses of private lands, such as the Endangered Species Act, have led to claims of government takings (Innes, Polasky, and Tschirhart 1998).

Another catalyst of conflict is declining economic activity in rural areas. In rural communities faced with declining population and economic activity, decisions to permit new land uses can prove controversial, especially when the facility is expected to generate economic activity but may also result in significant social and environmental costs. Examples of such facilities include waste disposal, gambling, or major industrial facilities. State legislation related to the siting of structures, such as large-scale confinement feeding operations for livestock and aquaculturc pens, reflects a divergence of attitudes related to the use of lands and natural resources. Finally, there is evidence of conflict between long-term and newer residents in rural areas. For example, many states have passed 'right-to-farm' laws in response to conflicts arising from incompatibilities between residential and agricultural uses of land. In other instances, newer residents have pushed for rigid, local land-use controls to prevent further development and to preserve the amenities that initially attracted them to the area. In rural areas with limited local land-use control experience, these pushes can generate controversy, especially if they are viewed as infringing on private property rights and traditional uses.

Objectives of this Book

The broad objective of this book is to present an overview of economic analyses of rural land-use change. Earlier books on the economics of land use (e.g., Barlowe 1958; Alonso 1964; VanKooten 1993) are rooted in the traditions of Ricardo and von Thünen and largely provide review and extensions of earlier concepts and models. Our point of departure is an emergent literature that uses modern economic methods to model land-use change and to investigate land-use policies in a cost-benefit framework. During the past decade, land use has been an active research area for economists. Theoretical models have been developed that explicitly consider the dynamic and potentially irreversible nature of land-use decisions. Moreover, procedures have been developed to estimate the external costs and benefits of changes in land use.

The book is divided into four parts. Part I offers an introduction to economic perspectives of rural land-use change and provides relevant background information on land-use trends. Following a discussion of recent land-use trends inChapter 2 (Ahearn and Alig), Chapter 3 (Alig and Ahearn) provides an overview of the effects of policy and technological change on land use. Rubin offers a discussion of the interaction between land-use trends and transportation policies inChapter 4. The introductory section of the book concludes with an overview of the demographic trends commensurate with recent land-use change, by Mageean and Bartlett (Chapter 5).

Part II focuses on theoretical and empirical models designed to gauge the determinants of rural land-use change. Scgcrson, Plantinga, and Irwin provide a synthesis of recent theoretical developments in characterizing land-use patterns and studying land-use decisions using an economic framework (Chapter 6). This summary is followed by a parallel synthesis of recent empirical developments. Irwin and Plantinga (Chapter 7) offer an overview of empirical methods employed to investigate the economic aspects of land-use change. The second part of the book concludes with two chapters ...