![]()

Chapter 1

The Sacred House: Domestic Space as Mandala

‘Cosmologies have more than aesthetic or intellectual interest. They are not simply fantasies of the mind floating about the hard realities of day-to-day living. They derive from lived experiences and at the same time give them meaning and direction.’

Yi-Fu Tuan, Man and Nature

Kholagaun Chhetri domestic space is a mandala. It consists of the house building and the compound that surrounds and encloses it. A mandala is a diagram of Hindu [tantric] cosmology that uses geometric space as a mode of representation. In Nepal, there is convincing evidence that Newars, the indigenous Hindu/Buddhist inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley, explicitly used the mandala form in the design of its cities, neighbourhoods, temples and houses.1 Chhetris of Kholagaun do not describe their houses as mandalas. Instead, in their everyday domestic practices as well as in the material and ritual construction of their houses, they build mandalas into their domestic space so that living in a house is at the same time an intimate lived experience and embodied knowledge of the divine cosmos. Further, the mandala form is one with which they, like Newars, are intimately familiar:

One lives and moves always within a series of ..mandalas: the Nepal mandala [the Kathmandu Valley], the mandalas of the cities, and the mandalas of house or temple. Conscious of being surrounded by these forms, it is not surprising that Newars tend to reproduce that form in all aspects of their lives…the order of the mandala has also become as habitual for Newars as linear constructions have for us. (Shepherd 1985:103)

Kholagaun Chhetris also move within the Nepal Mandala, the roughly circular Kathmandu Valley surrounding its sacred central cities and temples, as well as others. One of these is Chār Nārāyan, composed of the four Vishnu/Narayan shrines guarding the four quarters of the Valley and defining a mandala oriented by the cardinal directions: Ichangu Narayan in the north-west, Changu Narayan in the north-east, Bisankhu Narayan in the south-east and Shikhar Narayan in the southwest. In early November, when Vishnu wakes from his four months of sleep, Kholagaun Chhetris, along with other Nepalis, celebrate the event, known as Haribodhini Ekādasi, by fasting and travelling to Bisankhu Narayan Shrine, located on a hill just across the rice fields from their hamlet, where they worship Vishnu. This is also an occasion for the 36-mile pilgrimage to all four Narayan Shrines2 during which devotees embody the Nepal Mandala in their day-long circuit of travel and worship. Villagers say that everyone should do this pilgrimage at least once in their lives.

This chapter sets out how Chhetris of Nepal experience space: its nature, its organization and people’s relation to it. My theme is that, much like the Newars (Shepherd 1985), the mandala is the form in which Chhetris conceptualize space and I describe how, as a configuration of space, the mandala encodes not just Hindu [tantric] cosmology but also the means of acquiring knowledge of it. I then turn to the Hindu architectural texts—the Vastu Shastra—and commentaries upon them to show how this codified design system incorporates the cosmology and spatial principles of the mandala into the orientation of the house, room layout and location of domestic activities. I abstract from the mandala, and the Vastu Shastra’s use of it in architectural design, two spatial configurations that Kholagaun Chhetris build into houses and that give their dwellings a duality of structure and purpose: as auspicious places for the production of worldly prosperity with its attendant attachment to worldly things and the illusion caused by it; and as pure places for the attainment of religious knowledge through detachment and the attendant liberation from re-birth in the world.

I am not proposing that the relationship between the Vastu Shastra—including the incorporation of the mandala—and everyday domestic spatial practice is linear or causal. The Vastu Shastra and the mandala are not blueprints, normative rules, legitimising a hegemonic vedic tradition (Pollock quoted in Rowell 1993:471) that Kholagaun Chhetris explicitly and consciously adopt in the design, construction and use of their houses. Yet, as I will show in the following chapters, Kholagaun Chhetris’ architectural and spatial domestic practices appear to follow the Vastu Shastra—particularly in the orientation of their houses in relation to the cardinal directions and in the concern with the centre point. However, this is not because they are consciously using the specific prescriptions of these texts in the design of the room layout and use of their house spaces in the form of the mandala. Rather, it is because the Vastu Shastra and the everyday lifeworld of the Householder, for whose activities houses are designed to accommodate, draw upon the same cosmology, the former in an explicit and codified way, the latter in an implicit and taken-for-granted way. Still in the following I use codified architectural texts as well as treatises on the mandala—including their explanatory discourse of symbolism—to identify some of its important spatial features that I will argue in later chapters are spatially manifest in the both the intentional and conventional architecture of Chhetri houses and embodied in everyday domestic activities and rituals.

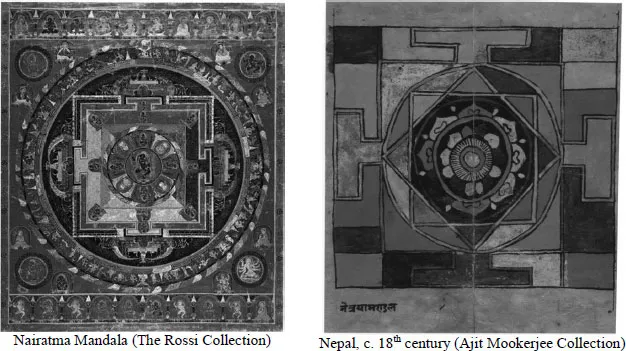

Mandala: A Cosmological Map

Throughout this book, I use the term ‘mandala’ in the generic sense of a mystic diagram.3 However, in Nepal, people use at least two terms, ‘mandala’ and ‘yantra’ to refer to drawings with sacred significance.4 Both mandala and yantra are sacred allegorical diagrams that represent the nature and order of the universe (see Figure 1.1). They are ‘map[s] of the cosmos…the whole universe in its essential plan’ (Tucci 2001:23). Tucci’s incisive description highlights three important attributes of mandalas and yantras. First, their primary referent is the cosmos but each represents it in a different graphic mode. Mandalas are generally composed of pictures and icons that depict religious concepts and deities who in turn personify the primary bodies and natural forces of the universe as well as the qualities of humans. Yantras are generally composed of purely geometric designs—squares, circles, triangles and the point—whose shapes likewise stand for religious concepts, deities and the natural forces and human qualities they personify. Second, mandalas and yantras are maps of the cosmos and, as such, the spatial arrangement of the pictures and geometric elements in the composition depict important characteristics of the cosmos. Third, more than just an allegorical map of the cosmos, mandalas and yantras are microcosms of it. Whether composed of pictographic or geometric elements, they are simultaneously cosmograms, religiograms, sociograms and psychograms revealing the normally hidden system of correlations between planes of existence: the cosmos, the deities, the human social world, and the body and psyche of the individual (Hopkins 1971:25, Tucci 2001:45). The macro-microcosmic equation is a central theme in Hindu [tantric] cosmology and ‘knowledge of such mystical connections leads to power in both Upanisadic and Tantric thought’ (Gourdriaan 1979:57-58) and is a basis for ritual action and its efficacy (see Daryn 2002: 164ff).

Figure 1.1 Two forms of the mandala

In Fernandez’ terms, both mandalas and yantras are metaphors, ‘commanding image[s]’ (Read 1951 in Fernandez 1986:204) that ‘bridge the abyss’ (Fernandez 1986:178) between all planes of existence and meaning, enabling experience and knowledge of the whole. Fernandez’ point is largely cognitive rather than practical: metaphors enable an intellectual understanding of the whole. Mandalas and yantras are more than this: they are instrumental and revelatory. Each can be used as a practical means of participating in the cosmos to harness its powers for worldly purposes to which humans become attached and each can be the focus for meditation and knowledge of the cosmos that leads to liberation from such attachment. In ritual action upon mandalas and yantras humans gain access to the powers of the cosmos through the system of correlations between planes of existence embedded in them; in understanding these correlations through contemplation, humans come to know the fundamental nature of the cosmic plane of existence.

In the literature, yantras are described more as instruments for action than for meditation, because the word ‘yantra’ literally means ‘instrument’ (Walker 1968 II:21, Kramrisch 1976, I:11, Hoens 1979:113, Khanna 1979:11) or ‘machine’ (Zimmer 1972:141, Bühnemann 2003:28). In Nepal this characterization of yantras only appears to be the case. For Kholagaun Chhetris among whom I have done fieldwork, yantra forms called ‘rekhi’ are diagrams composed of lines and geometric shapes drawn with coloured powder on the ground by household priests for a number of important rituals—particularly sacrifices performed in rites of passage and in rites of house consecration and inauguration. The geometric designs of these yantra mark out a sacred space and designated places where deities descend and are worshipped by people who seek their benefaction for worldly purposes. The performance of the worship rites involve physical actions of offerings and gestures to the deities in the yantra. A mandala, on the other hand, is an elaborate pictorial composition used in Nepal by Buddhists more as a visual guide for meditation that will lead to experience and knowledge of the ultimate transcendent truth of the cosmos. Yet, the distinction between instrumental action and revelatory meditation—as if meditation is not an embodied action—made in the literature may be false. Buddhist groups do use a mandala in ritual practice (e.g. Gellner 1992:190ff). Conversely, one of the themes I will develop throughout this book is that Kholagaun Chhetris’ action towards yantras—in their houses and in their ritual practices—is a non-contemplative form of embodied experience and knowledge that is also revelatory of the transcendent truth of the Universe. ‘A yantra … is a machine to stimulate inner visualization’ (Zimmer 1972:141). This can be done in bodily action upon the yantra just as much as in the bodily stillness of meditation upon its form. In their domestic and ritual activities, Kholagaun Chhetris’ bodily movements in relation to the yantra replicate the inward and outward movement of the eye and meditative mind in relation to mandalas. There is a more fundamental sense, then, in which mandala and yantra are indistinguishable in the ways they are used in Nepal. Both are an instrument of revelatory knowledge of the ultimate truth of the cosmos, the yantra through worldly-oriented, non-reflexive embodied action upon it and the mandala through inner-directed and highly reflexive but also embodied contemplation of it. We now turn to the truth that can be revealed through action and contemplation on mandalas and yantras.

Cosmology and Design of Mandala and Yantra

Even though they use different representational forms, pictographic mandalas and geometric yantras both express Tantric cosmological themes that infuse both Buddhism and Hinduism in Nepal. Tantrism is a ‘collection of practices and symbols of a ritualistic, sometimes magical character … [that] are all applied as a means of reaching spiritual emancipation or the realization of mundane aims’ (Goudriaan 1979:6).5 Hindu [tantric] cosmology is enigmatic and paradoxical. The fundamental reality it posits is an absolute unity that is a spaceless, timeless, causeless void. Juxtaposed to but derived from this ultimate cosmic unity is the ordered diversity of spaces, times, people, animals, natural forces, and material things of the everyday world that is ultimately an illusion. The origin of this worldly diversity is described in the self-sacrifice of the primeval cosmic being, Purusa. Purusha’s cosmogenic sacrifice is widely known in Nepal; in Kholagaun, people usually referred to the following lines from the Rig Veda ‘Hymn to Purusha’ (10:XC) when explaining to me the source and nature of the world:

The Brahmins from his [Purusha’s] mouth,

the Kshatriyas from his arms,

the Vaishyas from his stomach and

the Shudras from his feet.

The moon was born from his mind,

from his eyes was born the sun,

from his mouth [the deities] Indra and Agni, and

from his breath Vayu was born.

From his navel was the atmosphere,

from his head the sky was evolved,

from his feet the earth,

and the directions from his ear.

In this narrative, Purusha embodies the fundamental unity of the cosmos. All that can and will exist in the world is immanent in his body. His self-sacrifice is a creative act unleashing the diversity inherent and potential in his body and creating the microcosmic-macrocosmic system of correlations between planes of existence. As a result of this sacrifice, all perceptible time and space, every corporeal being and thing, and all natural energies and forces in the everyday world are both a distinct phenomenon and an expression of the whole unified cosmos. Every diverse being and thing is a visible and sensual microcosm that replicates but obscures the macrocosm.6 To focus on the former is to experience reality as constituted only by the diversity of sensible worldly phenomena; this is caused by ignorance which leads humans to become attached to people and things through social and material relations (see Gray 1995). To understand such attachments as the goal of life is to be caught in the continual cycle of death and rebirth (samsara). To focus on the latter—the macrocosm immanent in every thing—is to experience the everyday world of diversity as ultimately an illusion (maya) that hides the fundamental unity of the cosmos; this enlightened knowledge of the absolute leads humans to eschew the illusion of attachments. To understand the goal of life as ascetic detachment that dissolves the illusion of diversity leads to liberation (moksha) from the continual round of death and rebirth.

Despite their differences in representational form, mandalas and yantras share a basic design composition for expressing this cosmology: a centre point (bindhu) surrounded by a concentric girdle—either circular or polygonic—of line/s and space/s that provide the dynamic quality of movement, and an outer boundary line that marks off the sacred space of the mandala. This spatial configurat...